Bauhaus

[3] Staff at the Bauhaus included prominent artists such as Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Gunta Stölzl, and László Moholy-Nagy at various points.

Some buildings are characterized by rectangular features, for example protruding balconies with flat, chunky railings facing the street, and long banks of windows.

[6] After Germany's defeat in World War I and the establishment of the Weimar Republic, a renewed liberal spirit allowed an upsurge of radical experimentation in all the arts, which had been suppressed by the old regime.

[7] Just as important was the influence of the 19th-century English designer William Morris (1834–1896), who had argued that art should meet the needs of society and that there should be no distinction between form and function.

However, the most important influence on Bauhaus was modernism, a cultural movement whose origins lay as early as the 1880s, and which had already made its presence felt in Germany before the World War, despite the prevailing conservatism.

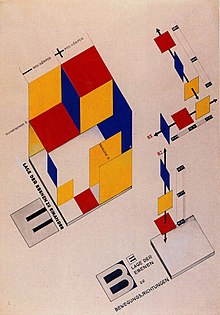

The design innovations commonly associated with Gropius and the Bauhaus—the radically simplified forms, the rationality and functionality, and the idea that mass production was reconcilable with the individual artistic spirit—were already partly developed in Germany before the Bauhaus was founded.

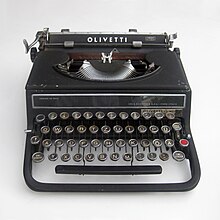

The German national designers' organization Deutscher Werkbund was formed in 1907 by Hermann Muthesius to harness the new potentials of mass production, with a mind towards preserving Germany's economic competitiveness with England.

Beginning in June 1907, Peter Behrens' pioneering industrial design work for the German electrical company AEG successfully integrated art and mass production on a large scale.

An entire group of working architects, including Erich Mendelsohn, Bruno Taut and Hans Poelzig, turned away from fanciful experimentation and towards rational, functional, sometimes standardized building.

[15] When van de Velde was forced to resign in 1915 because he was Belgian, he suggested Gropius, Hermann Obrist, and August Endell as possible successors.

This influence culminated with the addition of Der Blaue Reiter founding member Wassily Kandinsky to the faculty and ended when Itten resigned in late 1923.

Itten was replaced by the Hungarian designer László Moholy-Nagy, who rewrote the Vorkurs with a leaning towards the New Objectivity favoured by Gropius, which was analogous in some ways to the applied arts side of the debate.

Although this shift was an important one, it did not represent a radical break from the past so much as a small step in a broader, more gradual socio-economic movement that had been going on at least since 1907, when van de Velde had argued for a craft basis for design while Hermann Muthesius had begun implementing industrial prototypes.

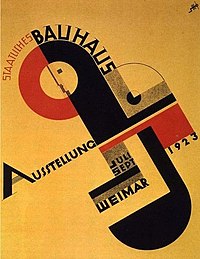

By 1923, however, Gropius was no longer evoking images of soaring Romanesque cathedrals and the craft-driven aesthetic of the "Völkisch movement", instead declaring "we want an architecture adapted to our world of machines, radios and fast cars.

Since the Weimar Republic lacked the number of raw materials available to the United States and Great Britain, it had to rely on the proficiency of a skilled labour force and an ability to export innovative and high-quality goods.

[1] Despite Gropius's protestations that as a war veteran and a patriot his work had no subversive political intent, the Berlin Bauhaus was pressured to close in April 1933.

When Hitler's chief engineer, Fritz Todt, began opening the new autobahns (highways) in 1935, many of the bridges and service stations were "bold examples of modernism", and among those submitting designs was Mies van der Rohe.

There were major commissions: one from the city of Dessau for five tightly designed "Laubenganghäuser" (apartment buildings with balcony access), which are still in use today, and another for the Bundesschule des Allgemeinen Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes (ADGB Trade Union School) in Bernau bei Berlin.

As opposed to Gropius's "study of essentials", and Meyer's research into user requirements, Mies advocated a "spatial implementation of intellectual decisions", which effectively meant an adoption of his own aesthetics.

It was the Bauhaus contemporaries Bruno Taut, Hans Poelzig and particularly Ernst May, as the city architects of Berlin, Dresden and Frankfurt respectively, who are rightfully credited with the thousands of socially progressive housing units built in Weimar Germany.

The Bauhaus had a major impact on art and architecture trends in Western Europe, Canada, the United States and Israel in the decades following its demise, as many of the artists involved fled, or were exiled by the Nazi regime.

[38] Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and Moholy-Nagy re-assembled in Britain during the mid-1930s and lived and worked in the Isokon housing development in Lawn Road in London before the war caught up with them.

The Harvard School was enormously influential in America in the late 1920s and early 1930s, producing such students as Philip Johnson, I. M. Pei, Lawrence Halprin and Paul Rudolph, among many others.

In the late 1930s, Mies van der Rohe re-settled in Chicago, enjoyed the sponsorship of the influential Philip Johnson, and became one of the world's pre-eminent architects.

(Breuer eventually lost a legal battle in Germany with Dutch architect/designer Mart Stam over patent rights to the cantilever chair design.

The physical plant at Dessau survived World War II and was operated as a design school with some architectural facilities by the German Democratic Republic.

"[44] Subsequent examples which have continued the philosophy of the Bauhaus include Black Mountain College, Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm and Domaine de Boisbuchet.

[45] The White City (Hebrew: העיר הלבנה), refers to a collection of over 4,000 buildings built in the Bauhaus or International Style in Tel Aviv from the 1930s by German Jewish architects who emigrated to the British Mandate of Palestine after the rise of the Nazis.

First, as Meyer put it, sport combatted a “one-sided emphasis on brainwork.”[57] In addition, Bauhaus instructors believed that students could better express themselves if they actively experienced the space, rhythms and movements of the body.

Sport and physical activity were essential to the interdisciplinary Bauhaus movement that developed revolutionary ideas and continues to shape our environments today.