Bayeux Tapestry

Now widely accepted to have been made in England, perhaps as a gift for William, it tells the story from the point of view of the conquering Normans and for centuries has been preserved in Normandy.

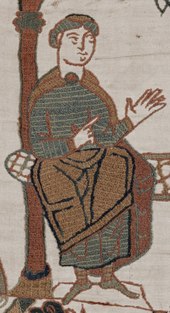

According to Sylvette Lemagnen, conservator of the tapestry, in her 2005 book La Tapisserie de Bayeux: The Bayeux tapestry is one of the supreme achievements of the Norman Romanesque .... Its survival almost intact over nine centuries is little short of miraculous ... Its exceptional length, the harmony and freshness of its colours, its exquisite workmanship, and the genius of its guiding spirit combine to make it endlessly fascinating.

[8][9][10] Howard B. Clarke has proposed that the designer of the tapestry (i.e., the individual responsible for its overall narrative and political argument) was Scolland, the abbot of St Augustine's Abbey in Canterbury, because of his previous position as head of the scriptorium at Mont Saint-Michel (famed for its illumination), his travels to Trajan's Column, and his connections to Wadard and Vital, two individuals identified in the tapestry.

Carola Hicks has suggested the tapestry could possibly have been commissioned by Edith of Wessex, widow of Edward the Confessor and sister of Harold.

"[10] George Beech suggests the tapestry was executed at the Abbey of Saint-Florent de Saumur in the Loire Valley and says the detailed depiction of the Breton campaign argues for additional sources in France.

[18] Andrew Bridgeford has suggested that the tapestry was actually of English design and encoded with secret messages meant to undermine Norman rule.

The Benedictine scholar Bernard de Montfaucon made more successful investigations and found that the sketch was of a small portion of a tapestry preserved at Bayeux Cathedral.

[22] The first detailed account in English was written by Smart Lethieullier, who was living in Paris in 1732–3, and was acquainted with Lancelot and de Montfaucon: it was not published, however, until 1767, as an appendix to Andrew Ducarel's Anglo-Norman Antiquities.

[21] After the Reign of Terror, the Fine Arts Commission, set up to safeguard national treasures in 1803, required it to be removed to Paris for display at the Musée Napoléon.

[21] When Napoleon abandoned his planned invasion of Britain the tapestry's propaganda value was lost and it was returned to Bayeux where the council displayed it on a winding apparatus of two cylinders.

[21] In 1816, the Society of Antiquaries of London commissioned its historical draughtsman, Charles Stothard, to visit Bayeux to make an accurate hand-coloured facsimile of the tapestry.

On 27 June 1944 the Gestapo took the tapestry to the Louvre, and on 18 August, three days before the Wehrmacht withdrew from Paris, Himmler sent a message (intercepted by Bletchley Park) ordering it to be taken to "a place of safety", thought to be Berlin.

The inventory listing of 1476 shows that the tapestry was being hung annually in Bayeux Cathedral for the week of the Feast of St John the Baptist; this was still the case in 1728, although by that time the purpose was merely to air the hanging, which was otherwise stored in a chest.

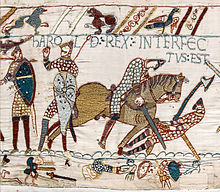

The tapestry's central zone contains most of the action, which sometimes overflows into the borders either for dramatic effect or because depictions would otherwise be very cramped (for example at Edward's death scene).

Tapestry fragments have been found in Scandinavia dating from the ninth century and it is thought that Norman and Anglo-Saxon embroidery developed from this sort of work.

[20] A monastic text from Ely, the Liber Eliensis, mentions a woven narrative wall-hanging commemorating the deeds of Byrhtnoth, killed in 991.

The Cloth of Saint Gereon, in Germany, is the largest of a group of fragments from hangings based on decorative Byzantine silks, including animals, that are probably the earliest European survivals.

[26](scene 33) The news of Harold's coronation is taken to Normandy, whereupon we are told that William is ordering a fleet of ships to be built although it is Bishop Odo shown issuing the instructions.

(scene 43) A house is burnt by two soldiers, which may indicate some ravaging of the local countryside on the part of the invaders, and underneath, on a smaller scale than the arsonists, a woman holds her boy's hand as she asks for humanity.

[26] A poem by Baldric of Dol describes a tapestry on the walls of the personal apartments of Adela of Normandy, which is very similar to the Bayeux depiction.

[26] The fact that the narrative extensively covers Harold's activities in Normandy (in 1064) indicates that the intention was to show a strong relationship between that expedition and the Norman Conquest starting two years later.

[42][43] Although political propaganda or personal emphasis may have somewhat distorted the historical accuracy of the story, the Bayeux Tapestry constitutes a visual record of medieval arms, apparel, and other objects unlike any other artifact surviving from this period.

The knights carry shields, but show no system of hereditary coats of arms—the beginnings of modern heraldic structure were in place, but would not become standard until the middle of the 12th century.

The American historian Stephen D. White, in a study of the tapestry,[44] has "cautioned against reading it as an English or Norman story, showing how the animal fables visible in the borders may instead offer a commentary on the dangers of conflict and the futility of pursuing power".

In 1997, the embroidery artist Jan Messent completed a reconstruction showing William accepting the surrender of English nobles at Berkhamsted (Beorcham), Hertfordshire, and his coronation.

[64] Because it resembles a modern comic strip or movie storyboard, is widely recognised, and is so distinctive in its artistic style, the Bayeux Tapestry has frequently been used or reimagined in a variety of different popular culture contexts.

George Wingfield Digby wrote in 1957: It was designed to tell a story to a largely illiterate public; it is like a strip cartoon, racy, emphatic, colourful, with a good deal of blood and thunder and some ribaldry.

A number of films have used sections of the tapestry in their opening credits or closing titles, including Disney's Bedknobs and Broomsticks, Anthony Mann's El Cid, Franco Zeffirelli's Hamlet, Frank Cassenti's La Chanson de Roland, Kevin Reynolds' Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, and Richard Fleischer's The Vikings.

The apocryphal account of Queen Matilda's creation of the tapestry is used, perhaps in order to demonstrate that Louis, one of the main characters, holds himself to mythological standards.

[74] At the behest of series showrunner Ryan Condal, the opening credits of the second season of the Game of Thrones prequel House of the Dragon (2024) were redesigned with an animated sequence in embroidery that was inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry.