Beiyang Army

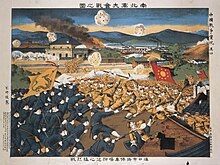

It was the centerpiece of a general reconstruction of the Qing military system in the wake of the Boxer Rebellion and the First Sino-Japanese War, becoming the dynasty's first regular army in terms of its training, equipment, and structure.

It played an instrumental role in the 1911 Revolution against the Qing dynasty, and, by dividing into warlord factions known as the Beiyang clique (Chinese: 北洋軍閥; pinyin: Běiyáng Jūnfá), ushered in a period of regional division.

The tensions between Russia and Japan in Manchuria in early 1904 caused Empress Dowager Cixi to agree to Yuan's request to raise more divisions, and he also used his senior position on the Army Reorganization Bureau to prioritize its funding.

By 1907 the Beiyang Army had 60,000 men organized in six divisions, some of whom served in the Inner City of Beijing as the emperor's palace guard, and on the eve of the 1911 Revolution it was the strongest military force of the Qing dynasty.

But his decision during that time to stop rotating officers led to Beiyang commanders turning their divisions into their own power base, using them to become politically influential figures in their own right after Yuan Shikai's death in 1916.

[5] Li Hongzhang, who founded the Huai Army in 1862 and later became the Viceroy (or governor-general) of Zhili and Commissioner of the Northern Seas (Beiyang), used it as his personal power base and provided for its equipment and funding.

[3][13] The Huai Army also did not have organized supply, medical, transport, or engineering services, so the soldiers on campaign had to live off the land or take goods from the local population,[5] as they did in Korea during the war.

In contrast to the simple organization of the braves, these two armies both had dedicated infantry, cavalry, artillery, engineering, and other technical branches, and specific attention was given to the recruitment, training, discipline, and pay of the soldiers.

The idea for it originated with Hanneken during the war, who wanted to create a foreign-trained corps to become the basis of a new imperial (instead of provincial) army, and Prince Gong submitted his plan in a memorial to the throne.

[19] The officer corps of this brigade-sized force in the late 1890s included five future presidents of the Republic of China, one prime minister, and multiple provincial governors; a testament to how influential the Beiyang Army would become.

[25] Yuan Shikai had been recognized as a military specialist by the Qing court in 1899, whose Right Division of the Guards Army was well trained and well equipped with standardized uniforms and weaponry, the latter consisting of Mauser rifles, Maxim machine guns, and one- to six-pounder artillery pieces.

[34][35] In January 1904, as tensions rose between Japan and Russia in China's Manchuria region shortly before the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, Yuan Shikai sent a memorial to the throne asking for funding to double the size of the Beiyang Army.

The New Army forces that were equipped Mauser and Krupp weaponry and participated in field maneuvers existed alongside traditional Bannermen, Green Standard, and local militia troops that still trained with matchlocks and long bows.

Foreign journalists and government officials from other parts of China were invited to watch the field maneuvers, which involved by some estimates as many as 50,000 troops, who were divided into two armies to stage a mock invasion of Zhili from Shandong.

[50] Graduates of the officer schools that Yuan had set up in Zhili were sent back to their home provinces to lead New Army units there, and cadres from Beiyang divisions that were personally selected by him were used in other parts of the country to create new formations.

In the summer of 1909 he named the emperor the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, a position that he held in an acting capacity as his regent, and appointed inexperienced princes to lead the Ministry of the Army, the Navy Bureau, and the General Staff Council.

[88] The regency in the final years of the Qing dynasty proved to be incapable of solving the challenges in China and faced growing ethnic resentment against the Manchus as well as revolutionary agitation against the monarchy, which became stronger after the election of provincial assembles in 1909.

[95] At this point Yuan ordered Feng Guozhang to stop his attack temporarily before entering Hanyang, even though Admiral Sa wanted to continue, ostensibly because the army needed to rest.

He wanted to use this as leverage to negotiate with the Qing, because by the time Hankou was retaken by imperial troops major uprisings had broken out in other parts of the empire, including political threats from the 20th Division commander near Beijing.

[97][98] Having consolidated his military power in the north,[99] and with his Beiyang Army remaining the core of the royalist forces,[100] Yuan then pressured Prince Chun to resign as imperial regent in early December.

[103][104][105] Because several provinces were in open rebellion by this point, among other factors, Yuan Shikai started talks for a political solution with Li Yuanhong, who was more interested after the weapons arsenal at Hanyang was captured by the Beiyang Army.

[112] The disagreement was made more complicated by the decentralized command structure of the former Qing dynasty's military forces, and their involvement in the 1911 Revolution set a precedent for the army to a have larger role in politics.

Yuan's relationship with the Beiyang generals and other northern commanders who also became his subordinates was a form of clientelism, and he used his position as president to provide them with power, including increased personal control over military units.

[139] Beiyang troops ended up abandoning Hunan as the province was taken over by local rebels and the Guangxi provincial army,[140] which happened around the same time that the war was resolved by the death of Yuan Shikai from natural causes in June 1916.

Besides causing the final break between the central government and the military governors in the southern provinces, it created the opportunity for the Beiyang and other northern generals to begin acting independently for their own political interests.

[142] Examples of these include Wang Zhanyuan in Hubei and Zhang Zuolin in Fengtien, who used their leverage to get Yuan to grant them authority over the civil administration in their provinces, giving them direct control over the funding of their military forces.

Li was seen as a potential mediator between the two factions in the war, and he restored the constitution and the National Assembly that Yuan had suppressed, but was unable to resolve the larger question of the distribution of power between the branches of government and the provinces.

The southern provinces used their armies to resist the Beiyang invasion,[152] with war breaking out as Guangxi and Guangdong clique troops entered Hunan in October to remove the northern forces.

[158] Duan spent the fall of 1917 trying to win support from other Beiyang commanders to continue the war against the south, while the southern movement was also split between the pro-war Sun Yat-sen and those that wanted to negotiate with Beijing.

The First Zhili–Fengtian War occurred in the spring and summer of 1922 when Zhang moved his troops into Beijing, but they were defeated and forced to withdraw to Manchuria, leaving the Zhili clique as the dominant warlord faction in northern and central China.