Belief

[2] There are various ways that contemporary philosophers have tried to describe beliefs, including as representations of ways that the world could be (Jerry Fodor), as dispositions to act as if certain things are true (Roderick Chisholm), as interpretive schemes for making sense of someone's actions (Daniel Dennett and Donald Davidson), or as mental states that fill a particular function (Hilary Putnam).

[4][5] Beliefs form a special class of mental representations since they do not involve sensory qualities in order to represent something, unlike perceptions or episodic memories.

A more holistic alternative to the "language of thought hypothesis" is the map-conception, which uses an analogy of maps to elucidate the nature of beliefs.

[4][11] For example, the fact that Brussels is halfway between Paris and Amsterdam can be expressed both linguistically as a sentence and in a map through its internal geometrical relations.

[4][14] As an analogy, a hard drive is defined in a functionalist manner: it performs the function of storing and retrieving digital data.

[4][12] From this perspective, it would make sense to ascribe the belief that a traffic light is red to a self-driving car behaving just like a human driver.

[4][15] The problem arises because the mechanisms shaping our behavior seem to be too complex to single out the general contribution of one particular belief for any possible situation.

Having an occurrent belief that the Grand Canyon is in Arizona involves entertaining the representation associated with this belief—for example, by actively thinking about it.

[38] Margaret Gilbert has offered a related account in terms of the joint commitment of a number of persons as a body to accept a certain belief.

Collective belief can play a role in social control[40] and serve as a touchstone for identifying and purging heresies,[41] deviancy[42] or political deviationism.

He imagines a twin Earth in another part of the universe that is exactly like ours, except that their water has a different chemical composition despite behaving just like ours.

[4][45][46] Epistemology is concerned with delineating the boundary between justified belief and opinion,[47] and involved generally with a theoretical philosophical study of knowledge.

In a notion derived from Plato's dialogue Theaetetus, where the epistemology of Socrates most clearly departs from that of the sophists, who appear to have defined knowledge as "justified true belief".

The tendency to base knowledge (episteme) on common opinion (doxa) Socrates dismisses, results from failing to distinguish a dispositive belief (doxa) from knowledge (episteme) when the opinion is regarded correct (n.b., orthé not alethia), in terms of right, and juristically so (according to the premises of the dialogue), which was the task of the rhetors to prove.

Plato dismisses this possibility of an affirmative relation between opinion and knowledge even when the one who opines grounds his belief on the rule and is able to add justification (logos: reasonable and necessarily plausible assertions/evidence/guidance) to it.

is true if and only if: That theory of knowledge suffered a significant setback with the discovery of Gettier problems, situations in which the above conditions were seemingly met but where many philosophers deny that anything is known.

"[54]: 3 On the other hand, Paul Boghossian argues that the justified true belief account is the "standard, widely accepted" definition of knowledge.

[59] Religion is a personal set or institutionalized system of religious attitudes, beliefs, and practices; the service or worship of God or the supernatural.

First self-applied as a term to the conservative doctrine outlined by anti-modernist Protestants in the United States,[65] "fundamentalism" in religious terms denotes strict adherence to an interpretation of scriptures that are generally associated with theologically conservative positions or traditional understandings of the text and are distrustful of innovative readings, new revelation, or alternative interpretations.

The philosophes took particular exception to many of the more fantastical claims of religions and directly challenged religious authority and the prevailing beliefs associated with the established churches.

In response to the liberalizing political and social movements, some religious groups attempted to integrate Enlightenment ideals of rationality, equality, and individual liberty into their belief systems, especially in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

This approach is a fairly consistent feature among smaller new religious movements that often rely on doctrine that claims a unique revelation by the founders or leaders, and considers it a matter of faith that the "correct" religion has a monopoly on truth.

[citation needed][70] People with inclusivist beliefs recognize some truth in all faith systems, highlighting agreements and minimizing differences.

with Interfaith dialogue or with the Christian Ecumenical movement, though in principle such attempts at pluralism are not necessarily inclusivist and many actors in such interactions (for example, the Roman Catholic Church) still hold to exclusivist dogma while participating in inter-religious organizations.

Typical reasons for adherence to religion include the following: Psychologist James Alcock also summarizes a number of apparent benefits which reinforce religious belief.

These include prayer appearing to account for successful resolution of problems, "a bulwark against existential anxiety and fear of annihilation," an increased sense of control, companionship with one's deity, a source of self-significance, and group identity.

[76] Typical reasons for rejection of religion include: Mainstream psychology and related disciplines have traditionally treated belief as if it were the simplest form of mental representation and therefore one of the building blocks of conscious thought.

Glover warns that some beliefs may not be entirely explicitly believed (for example, some people may not realize they have racist belief-systems adopted from their environment as a child).

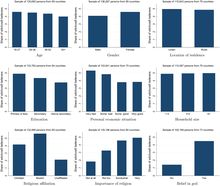

For example, a study estimated contemporary prevalence and associations with belief in witchcraft around the world, which (in its data) varied between 9% and 90% between nations and is still a widespread element in worldviews globally.

[99][100] Studies also suggested some uses of psychedelics can shift beliefs in some humans in certain ways, such as increasing attribution of consciousness to various entities (including plants and inanimate objects) and towards panpsychism and fatalism.