Bell X-1

A derivative of this same design, the Bell X-1A, having greater fuel capacity and hence longer rocket burning time, exceeded 1,600 miles per hour (2,600 km/h; 1,400 kn) in 1954.

Miles' chief aerodynamicist, Dennis Bancroft, was interviewed many years later in 1997 on his reason for needing an all-moving tailplane in his 1944 design.

In September 1946 a DH 108 tail-less jet aircraft was practicing for an attempt on the world speed record when it experienced violent pitching oscillations at Mach 0.875 and broke up.

Early specifications for the aircraft were for a piloted supersonic vehicle that could fly at 800 miles per hour (1,300 km/h) at 35,000 feet (11,000 m) for two to five minutes.

[4] On 16 March 1945, the U.S. Army Air Forces Flight Test Division and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) contracted with the Bell Aircraft Company to build three XS-1 (for "Experimental, Supersonic", later X-1) aircraft to obtain flight data on conditions in the transonic speed range.

For the design of the XS-1 the many unknowns relating to transonic and supersonic flight meant seeking every available source of information from governmental agencies, powerplant manufacturers and research institutions.

[7][8] Bell Aircraft aerodynamicists working with NACA laboratories predicted significant longitudinal trim changes during transonic flight.

John Stack and Robert Gilruth at NACA recommended that Bell mount the elevator on an adjustable horizontal stabilizer.

Scott Crossfield relates an inadvertent one-degree error flipping the X-1 on its back after being dropped from the mother plane.

Woolams completed nine more glide-flights over Pinecastle, with the B-29 dropping the aircraft at 29,000 feet (8,800 m) and the XS-1 landing 12 minutes later at about 110 miles per hour (180 km/h).

In March 1946 the #1 rocket plane was returned to Bell Aircraft in Buffalo, New York for modifications to prepare for the powered flight tests.

[4][16] After Woolams died while practicing for the National Air Races in August 1946, Chalmers "Slick" Goodlin was assigned as the primary Bell Aircraft test pilot for the X-1.

[18]: 96 [19][20] Flight tests of the X-1-2 (serial 46-063) would be conducted by NACA to provide design data for later production high-performance aircraft.

The first manned supersonic flight occurred on 14 October 1947, over the Mojave Desert in California,[21] less than a month after the U.S. Air Force had been created as a separate service.

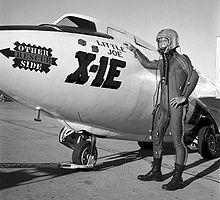

Captain Charles "Chuck" Yeager piloted USAF aircraft #46-062, nicknamed Glamorous Glennis for his wife.

[22] The news of a straight-wing supersonic aircraft surprised many American experts, who like their German counterparts during the war believed that a swept-wing design was necessary to break the sound barrier.

[4] On 10 June 1948, Air Force Secretary Stuart Symington announced that the sound barrier had been repeatedly broken by two experimental airplanes.

[23][24] On 5 January 1949, Yeager used Aircraft #46-062 to perform the only conventional (runway) launch of the X-1 program, attaining 23,000 ft (7,000 m) in 90 seconds.

[25] In 1997, the United States Postal Service issued a fiftieth anniversary commemorative stamp recognizing the Bell X1-6062 aircraft as the first aeronautical vehicle to fly at supersonic speed of approximately Mach 1.06 (1,299 km/h; 806.9 mph).

Only Yeager's skills as an aviator prevented disaster; later Mel Apt would lose his life testing the Bell X-2 under similar circumstances.

Longer and heavier than the original X-1, with a stepped canopy for better vision, the X-1A was powered by the same Reaction Motors XLR-11 rocket engine.

The X-1A dropped from maximum altitude to 25,000 feet (7,600 m), exposing the pilot to accelerations of as much as 8g, during which Yeager broke the canopy with his helmet before regaining control.

(Bell Model 58C) The X-1C (serial 48-1387)[30] was intended to test armaments and munitions in the high transonic and supersonic flight regimes.

On 24 July 1951, with Bell test pilot Jean "Skip" Ziegler at the controls, the X-1D was launched over Rogers Dry Lake, on what was to become the only successful flight of its career.