Belly dance

[13][14] The first known use of the term "belly dance" in English is found in Charles James Wills, In the land of the lion and sun: or, Modern Persia (1883).

The following attempt at categorization reflects the most common naming conventions:[17] In addition to these torso movements, dancers in many styles will use level changes, traveling steps, turns, and spins.

The arms are used to frame and accentuate movements of the hips, for dramatic gestures, and to create beautiful lines and shapes with the body.

[18] Later, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries, European travellers in the Middle East such as Edward Lane and Flaubert wrote extensively of the dancers they saw there, including the Awalim and Ghawazi of Egypt.

[citation needed] In his book, Andrew Hammond notes that practitioners of the art form agree that belly dance is lodged especially in Egyptian culture, he states: "the Greek historian Herodotus related the remarkable ability of Egyptians to create for themselves spontaneous fun, singing, clapping, and dancing in boats on the Nile during numerous religious festivals.

[34] Professional belly dance in Cairo has not been exclusive to native Egyptians, although the country prohibited foreign-born dancers from obtaining licenses for solo work for much of 2004 out of concern that potentially inauthentic performances would dilute its culture.

The few non-native Egyptians permitted to perform in an authentic way invigorated the dance circuit and helped spread global awareness of the art form.

[35] American-born Layla Taj is one example of a non-native Egyptian belly dancer who has performed extensively in Cairo and the Sinai resorts.

Also, thanks to Whenever Wherever in 2001, the belly dance fever began popularizing it in a large part of Latin America and later taking it to the United States.

At the Super Bowl LIV Halftime Show event she returned to the belly dance with rope during the transition from Ojos así thus to Whenever Wherever.

[43] Belly dance was popularized in the West during the Romantic movement of the 18th and 19th centuries, when Orientalist artists depicted romanticized images of harem life in the Ottoman Empire.

[44] Although there were dancers of this type at the 1876 Centennial in Philadelphia, it was not until the 1893 Chicago World's Fair that it gained national attention.

In his memoirs, Bloom states, "when the public learned that the literal translation was "belly dance", they delightedly concluded that it must be salacious and immoral ...

These included a Turkish dance, and Crissie Sheridan in 1897,[47] and Princess Rajah from 1904,[48] which features a dancer playing zills, doing "floor work", and balancing a chair in her teeth.

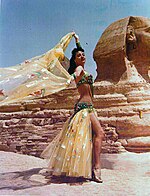

Hollywood began producing films such as The Sheik, Cleopatra, and Salomé, to capitalize on Western fantasies of the orient.

[citation needed] When immigrants from Arab states began to arrive in New York in the 1930s, dancers started to perform in nightclubs and restaurants.

[citation needed] Although using Turkish and Egyptian movements and music, American Cabaret ("AmCab") belly dancing has developed its own distinctive style, using props and encouraging audience interaction.

[50] In Spain and the Iberian Peninsula, the idea of exotic dancing existed throughout the Islamic era and sometimes included slavery.

When the Arab Umayyads conquered Spain, they sent Basque singers and dancers to Damascus and Egypt for training in the Middle Eastern style.

The first wave of interest in belly dancing in Australia was during the late 1970s to 1980s with the influx of migrants and refugees escaping troubles in the Middle East, including Lebanese Jamal Zraika.

These immigrants created a social scene including numerous Lebanese and Turkish restaurants, providing employment for belly dancers.

[60] Rather, it is generally agreed upon that belly dancing was brought to Greece via Asia Minor refugees during the Greek-Turkish population exchange of 1923.

Believing it to not represent Greek ideals and to be a relic of Turkish oppression, they argue it affiliates Greece with the broader Middle East rather than the west which the country supposedly belongs to.

[66] The costume or bedlah (referring to the bra, belt and skirt), of Egyptian Oriental dancers has also had the distinction as being the most popular style.

[67] Earlier costumes were made up of a full skirt, light chemise and tight cropped vest with heavy embellishments and jewelry.

[citation needed] As well as the two-piece bedlah costume, full-length dresses are sometimes worn, especially when dancing more earthy baladi styles.

Dresses range from closely fitting, highly decorated gowns, which often feature heavy embellishments and mesh-covered cutouts, to simpler designs which are often based on traditional clothing.

Modest, ethnically-inspired styles with stripes are common, but theatrical variants with mesh-filled cutouts and ornamented with sequins and bead work are also popular.

Many dancers ignore these rules, as they are rarely enforced, and performing in revealing outfits is common in Cairo and locales popular with tourists.

[76] Hollywood films regularly include sexualized belly dancers as part of Orientalized and exotic depictions of the Middle East.