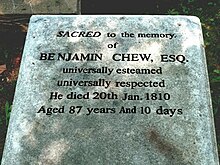

Benjamin Chew

Born into a Quaker family, Chew was known for precision and brevity in his legal arguments and his excellent memory, judgment, and knowledge of statutory law.

"[2] Chew lived and practiced law in Center City Philadelphia, four blocks from the Pennsylvania State House, later renamed Independence Hall, and provided pro bono legal counsel on substantive law to America's Founding Fathers during their creation of the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights.

The year before, Hamilton won a landmark case in American jurisprudence by his eloquent pro bono defense of publisher Peter Zenger.

After Hamilton's death in August 1741, Chew sailed to London to study law at the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, one of four Inns of Court.

He began attending London theatre and read what friends recommended; his journal during these years shows his process of adopting aspects of English refinement expected of gentlemen, which he continued after his return to the American colonies.

[4] Following his father's death, Chew returned to Pennsylvania in 1744, and began practicing law in Dover, Delaware, while supporting his siblings and stepmother.

[6] After early appointments in the Quaker-dominated government following his second marriage, he entered private practice in 1757; the following year joined the Anglican Church, and began a path to influence outside the Quaker elite.

[4] Mentored by Andrew Hamilton from an early age, Chew was highly effective in defending civil liberties and settling boundary disputes; he represented William Penn's descendants and their proprietorships as the largest landholders in the Province of Pennsylvania, for over 60 years.

During the American Revolutionary War, the Executive Council governing the new state removed him from office in 1777 and kept him in preventive detention in New Jersey until after the British forces left the Philadelphia region.

Twenty-one representatives of New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire attended the Congress.

The conference concluded on October 26, and in November, Governor Denny announced to the Pennsylvania Assembly that "a general peace was secured at Easton.

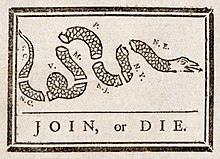

"[13] In a letter warning the Crown against enacting the Stamp Act, Attorney General Benjamin Chew described the mood in America: "…it is impossible to say to what length their irritated and turbulent Spirits may carry them.

Chew received the highest compliment Pennsylvania could pay him: he was appointed by Governor Thomas Mifflin as President of the High Court, despite the fact that he was by then close to seventy.

As a lifelong pacifist, however, Chew believed that protest and reform were necessary to resolve the ongoing American conflicts with the British Parliament.

"[21] "As a lawyer, [Chew] believed that the warrant infringed on his rights as a free man; moreover, it violated the first principle of justice by prejudging him unheard.

[21] After the Revolution, Benjamin Chew's broad social circles continued to include representatives of many faiths, as well as friends and politicians with many disparate points of view.

[22] Chew continued to participate in the meetings of the Tammany Society, to honor Tamanend, the Lenni-Lenape chief who first negotiated peace agreements with William Penn.

[24] For almost five decades, the household on Third Street was filled by Benjamin and Elizabeth Chew, their son Benjamin, and their daughters Anna Marie, Elizabeth, Sarah, Margaret (Peggy), Juliana, Henrietta, Sophia, Maria, Harriet, and Catherine, all of whom were actively engaged in the social, civic, and cultural life of the nation's first capital.

The Chews entertained many visiting dignitaries, such as John Penn, Tench Francis Jr., Robert, Thomas, and Samuel Wharton, Thomas Willing, John Cadwalader, Chief Justice William Allen and his wife Margaret, daughter of Andrew Hamilton, Dr. William Smith, Provost of the College of Philadelphia, botanist John Bartram, Edward Shippen III, Edward Shippen IV, and Peggy Shippen, Thomas Mifflin, later to become Governor of Pennsylvania, and Brigadier General Henry Bouquet, hero of the French and Indian War.

"Led by Mrs. Washington, Mrs. Morris, and 'the dazzling Mrs. Bingham,' as Abigail Adams called her, the city embarked on a lavish program of public and private entertainment patterned on English and French models.

"[31] Mrs. Adams reports being pleasantly surprised by "an agreeable society and friendliness kept up with all the principal families, who appear to live in great harmony, and we are met at all the parties [with] nearly the same company.

[36] On August 4, 1777, when the Executive Committee of the Continental Congress decided to place Chew in preventive detention in New Jersey, his wife and children vacated Cliveden and returned to their Third Street home.

[37] After Chew was released from parole in May 1778, he decided to move his family to Whitehall, their estate in Delaware, to buffer them from the political turbulence of Philadelphia.

[38] While in Delaware, the Chews rented their house on Third Street to Don Juan de Miralles (the Spanish representative to the American government); the Marquis de Chastellux (principal liaison officer between the French Commander-in-Chief and George Washington); and to George and Martha Washington, from November 1781 to March 1782, during the Second Continental Congress.

Cannonballs from the Battle of Germantown were embedded in its walls until 1972, when Chew's descendants donated the house to the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

In 1768, recognizing the boy's early genius, Chew sold Allen, then eight years old, and all members of his immediate family to Stokley Sturgis, a known abolitionist[citation needed] and owner of a neighboring property in Delaware.