Beonna of East Anglia

The very few primary sources for Beonna consist of bare references to his accession or rule written by late chroniclers, that until quite recently were impossible to verify.

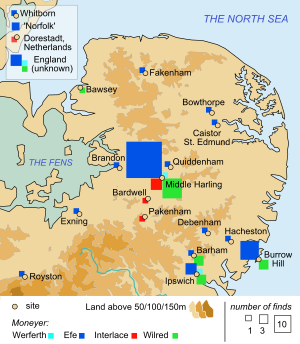

They have allowed scholars to make deductions about economic and linguistic links that existed between East Anglia and other parts of both England and northern Europe during his reign, as well as aspects of his own identity and rule.

The historian Barbara Yorke has maintained that this is due to the destruction of the kingdom's monasteries and the disappearance of both of the East Anglian Episcopal sees, which were caused by Viking raids and later settlement.

[7][note 2] Another source is a passage in the 12th-century Chronicon ex chronicis, once thought to have been written by Florence of Worcester, which stated that "Beornus" was king of the East Angles.

[9][10][11][12][note 4] The annal for 749 in The Flowers of History, written by the chronicler Matthew Paris in the 13th century, also relates that "Ethelwold, king of the East Angles, died, and Beonna and Ethelbert divided his dominions between them".

It is generally accepted that Alberht and the later Æthelberht II, who ruled East Anglia until his death in 794, are different kings,[14] but the historian D. P. Kirby has identified them as being one person.

[citation needed] An alternative theory is that the Latin annal that mentioned Hunbeanna was derived from an Old English source and that the translator scribe misread the opening word here for part of the name of Beonna.

[citation needed] Charles Oman proposed that Beornred, who in 757 emerged for a short time as ruler of Mercia before being driven out by Offa,[note 5] could be the same person as Beonna.

Alberht, who had attempted to re-establish East Anglia as an independent kingdom and rule alone, and had succeeded for a short time, was deposed by Beornred/Beonna when he arrived as an exile in about 760.

[25] A growing shortage of available bullion in north-western Europe during the first half of the 8th century was probably the main cause for a deterioration in the proportion of precious metal found in locally produced sceattas.

In around 740, Eadberht of Northumbria became the first king to respond to this crisis by issuing a remodelled coinage, of a consistent weight and a high proportion of silver, which eventually replaced the debased currency.

However, as Eadberht's reign began in 738, several years before Beonna became king in East Anglia, the coins cannot be related to each other closely enough to construct a reliable chronology.

[33] Efe's obverse dies show the king's name and title, usually spelt with a mixture of runes and Latin script, with some aspects of the coins occasionally ill-drawn or omitted altogether.

Wilred's coins can be used to demonstrate that Offa's influence over the East Angles occurred at an earlier date than has previously been supposed, but are of little use in determining a secure chronology for Beonna's reign.

A specimen of this type (now lost) was found at Dorestad, which was during Beonna's time an important trading centre: these coins resemble Frankish or Frisian deniers that were issued from the Maastricht area during this period.

[38] Beonna's rule coincided with the anointing of Pippin III as king of the Franks after 742 and the subsequent disempowerment of the Merovingian dynasty, and also with the martyrdom of Saint Boniface and his followers in Frisia in 754.