Specimens of Archaeopteryx

[5] The feather was first described in a series of correspondence letters between Hermann von Meyer and Heinrich Georg Bronn, the editor of the German Jahrbuch für Mineralogie journal.

Examining the fossil on both counterpart split slabs, von Meyer immediately recognized it as an asymmetrical bird feather, most likely from a wing, with an "obtusely angled tip" and a "here and there gaping vane", and noted its blackish appearance.

Six weeks after writing this first letter in August 1861, von Meyer wrote again to the editor stating that he had been informed of a nearly-complete skeleton of a feathered animal from the same lithographic shale deposits, which would later be known as the London specimen.

[4][6] Though 1860 is often the year named for the feather's discovery, there is no proof of this date, and some authors consider it more likely to have been found in 1861, as it seems reasonable that von Meyer's original letter was likely sent not longer after it came into his possession.

25 meters of the limestone profile of Upper Solnhofen strata are exposed here, but no information was given about which horizon the feather originated from, though the fossil's dark colour may indicate that it came from a deeper level where it was protected from weathering.

Though it is theoretically possible to determine which it is, studying the physical component of the preserved dark film would require taking away a certain amount of the material from the fossil, and no curator was willing grant permission for such damage to a valuable holotype specimen.

[23] Witte later recounted his visit with Wagner in 1863 in a letter to the editor of "Neues Jahrbuch": When I first told him of the specimen in order to urge him to buy it for the Munich Collections, he reacted with absolute incredulity, since, according to his view, a feathered creature could only be a bird.

Wellnhofer points out that his reasoning behind this opinion was likely due to his anti-Darwinist approach to paleontology, which is confirmed in Wagner's November 1862 talk, wherein he makes a statement on the new fossil with the intention to "ward off Darwinian misinterpretations of our new Saurian".

[28] While the arguments about the nature of the new feathered animal were underway, negotiations were taking place between Dr. Häberlein and the British Museum of London, as the offer of sale to the Bavarian State Collection had failed.

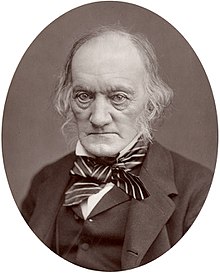

Then a staunch opponent to the theory of Darwinian evolution, Owen was intensely interested in this so-called transitional fossil that showed a strange mix of avian and reptilian characteristics.

Owing to its overall similarity to the structure of modern birds, Owen postulated a toothless, horny beak-like instrument "fitted for preening", and misinterpreted the fragment of an upper jaw with teeth, located next to the pelvis on the specimen, as the remains of a fish.

[41] In the subsequent years of the 19th century, the London specimen was subject to a number of analyses by other researchers of historical importance, including Thomas Huxley, Othniel Charles Marsh, Wilhelm Dames, and Bronislav Petronievics.

Its discovery and subsequent descriptions, a mere handful of years after Darwin's On the Origin of Species, fulfilled the hope of a truly transitional form in its then-unique amalgamation of bird and reptilian characters.

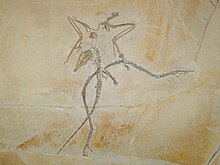

[38][52] The left hindlimb is completely preserved on the main slab, and shows a slightly curved femur, a proximal muscle scar likely to represent the greater trochanter, a slender tibia and fibula, a remarkably birdlike tibiotarsus, and the four delicate toes of the foot.

After several years of tension, the fossil was finally reclaimed by Germany for a sum of 20,000 marks in April 1880, whereby von Siemens made it immediately available for research by the Mineralogical Museum of Berlin.

He described his findings in a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in York, England, where he reported previously unnoticed features of the fossils including real teeth.

[76] Its well-preserved skeleton and the preserved feathers of its wings and tail have made it of considerable interest to a wide range of scientific study, beginning with Wilhelm Dames and Carl Vogt shortly following its discovery.

[77][78] Researchers believed the animal likely died by drowning in a Jurassic Solnhofen lake, floated on the surface for some time, and then sunk to the lagoon floor where it was deposited in calcium-rich mud.

[99] In 1958, Eduard Opitsch, owner of the quarry, allowed the fossil to be taken away by visiting geologist Klaus Fesefeldt who believed it was some vertebrate and sent it to the University of Erlangen where paleontologist Professor Florian Heller identified it correctly and further prepared it.

In negotiations with Princess Therese zu Oettingen-Spielberg of the Bayerische Staatssamlung für Paläontologie und Geologie Opitsch, though never demanding an exact amount, had already vaguely indicated a price of about 40,000 DM.

To this day, any further research on the specimen must necessarily be conducted through a small number of relatively precise casts, photographs and X-ray images of both fossil slabs, which had been fortuitously made before its disappearance.

[111] The Maxberg specimen shows the greatest extent of disintegration among the Archaeopteryx body fossils, exemplified by its loss of skull, cervicals and parts of the hindlimb, indicating an extended period of transport before deposition on the lagoon floor.

In March 1860, a seemingly unremarkable vertebrate fossil from Riedenburg, Bavaria, was purchased from von Meyer by the then-director of the Teyler Museum, Jacob Gijsbertus Samuël van Breda (Winkler 1865).

In 1972, Mayer, himself already eighty-four years old, on the occasion of the opening of a new Eichstätt natural history museum, invited Peter Wellnhofer to examine the specimen and publish a scientific analysis.

Among other things the skull presents evidence of a certain extent of cranial kineses by way of a preserving an articular surface on the ventral side, showing that sliding movements were possible between the lacrymal and jugal.

[132] The quarryman honestly informed the director of the quarry, who legally owned any finds by worker, and the next day Wellnhofer was called on to come examine the fossil and was asked to take over the scientific study of the new specimen.

The head of the Solenhofer Aktien-Verein, Dr. Michael Bücker, expressed interest in selling the specimen around the end of the loan period to Munich, and eventually the fossil was offered to the Bavarian State Collection for 2 million deutschmarks.

Much of the rest of the skeleton is excellently preserved, including the normal vertebral count in Archaeopteryx, cervical ribs, gastralia, naturally-contacted (and not co-ossified) scapula and coracoid, pelvic girdle, and hind limbs.

For example, the right foot was preserved so tightly flexed that the claws of the first and fourth toes are overlapping, indicating that a grasping or perching function was present in Archaeopteryx, possibly as sophisticated as that of modern birds.

After the specimen was recognized for what it was—the wing bones of an Archaeopteryx—an agreement was arranged for the fossil to go on an unlimited loan to the Solnhofen Museum, and the owners subsequently agreed to let it undergo scientific investigation by the Bavarian State Collection in Munich.