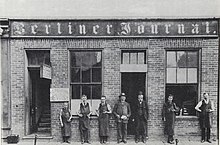

Berliner Journal

A 1918 Order in Council prohibiting the use of "enemy languages" in Canadian publications led the Journal to publishing only in English beginning in October 1918 and then folding altogether that December.

[14][15][note 4] In the absence of copyright laws, the paper's content included columns reprinted verbatim from German sources – especially the German-American dailies Wechselblätter and Texas Vorwärts – as well as material translated from the English-Canadian press.

[17] Motz and Rittinger edited the translated pieces, removing content they thought sensationalist and which "the average German could only poorly digest".

[25] As the paper's editor, Motz believed it important for the press and social organizations to cooperate on shared causes, evidenced by the Journal pushing for German to be taught in Ontario schools and the promotion of German cultural events;[26] in 1897, Motz, along with community leader George Rumpel, headed the committee in charge of the dedication of a bust of Kaiser Wilhelm I in Berlin's Victoria Park.

The editors made clear that the paper supported the Union, speaking favourably of Abraham Lincoln and German Americans Carl Schurz, Franz Sigel and Louis Blenker.

[36] News of the 1870 Franco-Prussian War and German unification in 1870–71 dominated the paper's coverage;[36] readers desperate to know about the conclusion of battles travelled "many miles on foot, or by vehicle, to procure their copy of the Journal at the press.

[43] As anti-liberal trends expanded in Germany in the end of the 19th century, Motz critiqued the German government's actions,[44] especially the lack of both parliamentary rights and freedom of speech.

[50] Zeitung's editorials complained of "English nativism in Canada" and sought to promote German ways,[51] while the Journal instead focused on more pressing German-Canadian issues.

[56] Their sons took over the newspaper that year;[36] William John Motz served as local editor and Herman Rittinger as the technical publisher-director.

[58] After graduating from St. Jerome's College in 1873, Rittinger learned the printing trade at his father's shop and apprenticed for newspapers in Guelph, Toronto, Buffalo, New York and Chicago.

[63] He studied classics and philosophy under St. Jerome's founder, Friar Louis Funcken,[63] whom Kalbfleisch describes as "a preist of great erudition and exceptional pedagogical ability.

"[64][note 8] Motz subsequently obtained a BA in political science at the University of Toronto and an MA at St. Francis Xavier College in New York.

[68] Both Motz and Rittinger's views as espoused in the Journal were heavily influenced by their education under Funcken,[67] promoting the use of the German language, civic duty and continuing to criticize the anti-liberal trends in Germany and Prussia.

With the help of a $5,000 loan (equivalent to CA$160,000 in 2023) from local manufacturer and politician Louis Jacob Breithaupt, it moved to 15 Queen Street South in 1906.

[79] These numbers made it the most widely read German-language newspaper in Canada, with subscribers in Toronto, Ottawa, Halifax, Montreal and British Columbia.

[80] After moving from the Glocke to the Journal, Rittinger continued to publish his widely popular letters to the editor, signed under the pseudonym "Joe Klotzkopp".

Is there anything more beautiful in this world than to have yourself shot to death for the kings and emperors, or afterwards, when the war is over, to hobble around without an arm or leg, but with a silver medal on your chest?

[58] The dialect was common among the Germans of nineteenth-century Ontario, and German-language newspapers across Upper and Lower Canada and Nova Scotia regularly published letters using it.

"[71] Researcher Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek suggests that because the letters are restricted thematically to contemporaneous issues, their value to modern scholars resides in studying their style and use of language, along with "their humoristic and ironic mode of narration.

"[84] Scholar Hermann Boeschenstein writes that the letters mediate between European and Canadian cultures, and that "Rittinger proved ... that immigration can be conducive to the exchange and dissemination of valuable experience and ideas".

[88] Kalbfleisch remarks that Rittinger's "wit and humour were ever present adjunct to his racy and picturesque style", especially within the Joe Klotzkopp letters.

[86] He compares Rittinger's work to that of Thomas Chandler Haliburton and Stephen Leacock, and ultimately concludes that "[h]ad he written in the English language his reputation in Canada would now be secure.

"[101] The Journal encourage German-Canadians to comply with all Canadian laws, while also stating in a 13 January 1915 editorial that each immigrant had a right to "entertain in his heart sympathy for the old homeland.

Chambers appealed to Secretary of State Louis Coderre for a warrant to suppress the newspaper, but was unsuccessful after Waterloo North Member of Parliament William George Weichel defended both the paper and Motz's character.

Despite the admission, Chambers still refused to admonish Laut, explaining to Motz that publishing a German-language newspaper while being of "German extraction ... imposes upon you certain standards of carefulness which might not be expected of others.

[98] After the referendum passed successfully and the city name officially changed from Berlin to Kitchener, editorial content largely disappeared from the newspaper.

[120] On 25 September 1918, the Canadian Government passed an Order in Council prohibiting "the publication of books, newspapers, magazines or any printed matter in the language of any country or people for the time being at war with Great Britain.

[122] A piece in the 4 December 1918 issue of the Journal questioned the lateness of the Order, asking: "The war ended six weeks after the Union Government prohibited German papers in Canada.

"[123] Historian Werner A. Bausenhart suggests the Order was likely connected to Newton Rowell's attempt to consolidate news information through his creation of The Canadian Official Record in September 1918.

The order permitted publication in German only if every article had an accompanying English or French translation, an option the editors rejected as impractical.