Hector Berlioz

The elder son of a provincial physician, Berlioz was expected to follow his father into medicine, and he attended a Parisian medical college before defying his family by taking up music as a profession.

He briefly moderated his style sufficiently to win France's premier music prize – the Prix de Rome – in 1830, but he learned little from the academics of the Paris Conservatoire.

[11] He recalled in his Mémoires that he enjoyed geography, especially books about travel, to which his mind would sometimes wander when he was supposed to be studying Latin; the classics nonetheless made an impression on him, and he was moved to tears by Virgil's account of the tragedy of Dido and Aeneas.

Trying to master harmony, he read Rameau's Traité de l'harmonie, which proved incomprehensible to a novice, but Charles-Simon Catel's simpler treatise on the subject made it clearer to him.

[25] By the end of 1822 he felt that his attempts to learn composition needed to be augmented with formal tuition, and he approached Jean-François Le Sueur, director of the Royal Chapel and professor at the Conservatoire, who accepted him as a private pupil.

He also conceived a passion for Kemble's leading lady, Harriet Smithson – his biographer Hugh Macdonald calls it "emotional derangement" – and obsessively pursued her, without success, for several years.

[n 7] Nevertheless, he was greatly encouraged by the vociferous approval of his performers, and the applause from musicians in the audience, including his Conservatoire professors, the directors of the Opéra and Opéra-Comique, and the composers Auber and Hérold.

His entry the previous year, Cléopâtre, had attracted disapproval from the judges because to highly conservative musicians it "betrayed dangerous tendencies", and for his 1830 offering he carefully modified his natural style to meet official approval.

On the way back to Rome he began work on a piece for narrator, solo voices, chorus and orchestra, Le Retour à la vie (The Return to Life, later renamed Lélio), a sequel to the Symphonie fantastique.

Heeding Vernet's advice that it would be prudent to delay his return to Paris, where the Conservatoire authorities might be less indulgent about his premature ending of his studies, he made a leisurely journey back, detouring via La Côte-Saint-André to see his family.

The programme included the overture of Les Francs-juges, the Symphonie fantastique – extensively revised since its premiere – and Le Retour à la vie, in which Bocage, a popular actor, declaimed the monologues.

[53] Among the musicians present were Liszt, Frédéric Chopin and Niccolò Paganini; writers included Alexandre Dumas, Théophile Gautier, Heinrich Heine, Victor Hugo and George Sand.

Biographers differ about whether and to what extent Smithson's receptiveness to Berlioz's wooing was motivated by financial considerations;[n 11] but she accepted him, and in the face of strong opposition from both their families they were married at the British Embassy in Paris on 3 October 1833.

Macdonald suggests that Berlioz may have sought distraction from his grief by going ahead with a planned series of concerts in St Petersburg and Moscow, but far from rejuvenating him, the trip sapped his remaining strength.

[116] Forty years earlier, Sir Thomas Beecham, a lifelong proponent of Berlioz's music, commented similarly, writing that although, for example, Mozart was a greater composer, his music drew on the works of his predecessors, whereas Berlioz's works were all wholly original: "the Symphonie fantastique or La Damnation de Faust broke upon the world like some unaccountable effort of spontaneous generation which had dispensed with the machinery of normal parentage".

[119][120] It is common ground for critics and defenders that his approach to harmony and musical structure conforms to no established rules; his detractors ascribe this to ignorance, and his proponents to independent-minded adventurousness.

He explained his practice in an 1837 article: accenting weak beats at the expense of the strong, alternating triple and duple groups of notes and using unexpected rhythmic themes independent of the main melody.

Macdonald has questioned Berlioz's fondness for divided cellos and basses in dense, low chords, but he emphasises that such contentious points are rare compared with "the felicities and masterstrokes" abounding in the scores.

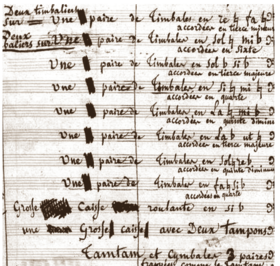

[128] Berlioz took instruments hitherto used for special purposes and introduced them into his regular orchestra: Macdonald mentions the harp, the cor anglais, the bass clarinet and the valve trumpet.

Among the characteristic touches in Berlioz's orchestration singled out by Macdonald are the wind "chattering on repeated notes" for brilliance, or being used to add "sombre colour" to Romeo's arrival at the Capulets' vault, and the "Chœur d'ombres" in Lélio.

Felix Weingartner, an early 20th-century champion of the composer, wrote in 1904 that it did not reach the level of the Symphonie fantastique;[137] fifty years later Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor found it "romantic and picturesque ... Berlioz at his best".

[158] His libretto, based on Much Ado About Nothing, omits Shakespeare's darker sub-plots and replaces the clowns Dogberry and Verges with an invention of his own, the tiresome and pompous music master Somarone.

[163] The orchestra does not play at all in the "Quaerens me" section, and what Cairns calls "the apocalyptic armoury" is reserved for special moments of colour and emphasis: "its purpose is not merely spectacular but architectural, to clarify the musical structure and open up multiple perspectives.

[6] A cantata for double chorus and large orchestra in honour of Napoleon III, L'Impériale, described by Berlioz as "en style énorme", was played several times at the 1855 exhibition, but has subsequently remained a rarity.

[171] The first version, written at the Villa Medici, had been in fairly regular rhythm, but for his revision Berlioz made the strophic outline less clear-cut, and added optional orchestral parts for the last stanza, which brings the song to a quiet close.

His Treatise on Instrumentation (1844) began as a series of articles and remained a standard work on orchestration throughout the 19th century; when Richard Strauss was commissioned to revise it in 1905 he added new material but did not change Berlioz's original text.

Cairns translated and edited Berlioz's Mémoires in 1969, and published a two-volume, 1500-page study of the composer (1989 and 1999), described in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians as "one of the masterpieces of modern biography".

[192]By the 1950s the critical climate was changing, although in 1954 the fifth edition of Grove carried this verdict from Léon Vallas: Berlioz, in truth, never did contrive to express what he aimed at in the impeccable manner he desired.

In 1950 Barzun made the point that although Berlioz was praised by his artistic peers, including Schumann, Wagner, César Franck and Modest Mussorgsky, the public had heard little of his music until recordings became widely available.

Singers who have recorded Les Nuits d'été include Victoria de los Ángeles, Leontyne Price, Janet Baker, Régine Crespin, Jessye Norman and Kiri Te Kanawa,[203] and more recently, Karen Cargill and Susan Graham.