Bernard Levin

After a short spell in a lowly job at the BBC selecting press cuttings for use in programmes, he secured a post as a junior member of the editorial staff of a weekly periodical, Truth, in 1953.

Levin reviewed television for the Manchester Guardian and wrote a weekly political column in The Spectator noted for its irreverence and influence on modern parliamentary sketches.

After a disagreement with the proprietor of the paper over attempted censorship of his column in 1970, Levin moved to The Times where, with one break of just over a year in 1981–82, he remained as resident columnist until his retirement, covering a wide range of topics, both serious and comic.

From the early 1990s, Levin developed Alzheimer's disease, which eventually forced him to give up his regular column in 1997, and to stop writing altogether not long afterwards.

The cuisine was traditional Jewish, with fried fish as one cornerstone of the repertoire, and chicken as another – boiled, roast, or in soup with lokshen (noodles), kreplach or kneidlach.

[10] Levin was a bright child and, encouraged by his mother, he worked hard enough to win a scholarship to the independent school Christ's Hospital in the countryside near Horsham, West Sussex.

Macnutt was a strict, even bullying, teacher, and was feared rather than loved by his pupils, but Levin learned Classics well, and acquired a lifelong fondness for placing Latin tags and quotations in his writing.

[1][12] In the local streets, the school's conspicuous uniform, including a blue coat, knee breeches and yellow socks, attracted unwanted attention.

[1] His talents were recognised and encouraged by LSE tutors including Karl Popper and Harold Laski; Levin's deep affection for both did not prevent his perfecting a comic impersonation of the latter.

The paper had recently been taken over by the liberal publisher Ronald Staples who together with his new editor Vincent Evans was determined to cleanse it of its previous right-wing racist reputation.

[11] While still at Truth, Levin was invited to write a column in The Manchester Guardian about ITV, Britain's first commercial television channel, launched in 1955.

[11] Levin gave the opening programmes a kindly review, but by the fourth day of commercial television he was beginning to baulk: "There has been nothing to get our teeth into apart from three different brands of cake-mix and a patent doughnut".

[28] Later in that year, after the general election victory of another of his bêtes noires, Harold Macmillan, Levin gave up the Taper column, professing himself to be in despair.

[12] Concurrently with his work at The Spectator, Levin was the drama critic of The Daily Express from 1959, offending many in theatrical circles by his outspoken verdicts.

He gave a fellow-critic an edition of Shaw's collected criticism, writing inside the cover, "'In the hope that when you come across the phrases I have already stolen you will keep quiet about it".

Meeting him in London the publisher Rupert Hart-Davis did not immediately recognise him: "He looks about sixteen, and at first I thought he was someone's little boy brought along to see the fun – very Jewish, with wavy fairish hair, very intelligent and agreeable to talk to".

He wrote several articles on the subject, and when reviewing books made a point of praising good indexes and condemning bad ones.

[37] In June 1970, during the general election campaign, Levin fell out with the proprietors of The Daily Mail, Lord Rothermere and his son Vere Harmsworth.

[11] Among the perquisites of the Times appointment were a company car and a large and splendid office at the paper's building in Printing House Square, London.

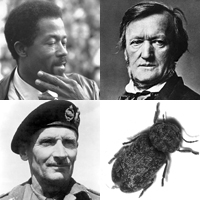

His range was prodigious; he published nine volumes of his selected journalism of which the first, Taking Sides, covered subjects as diverse as the death watch beetle, Field Marshal Montgomery, Wagner, homophobia, censorship, Eldridge Cleaver, arachnophobia, theatrical nudity, and the North Thames Gas Board.

[41] After Levin's death The Times published an article opining that information made public since 1971 "strongly supported" his criticisms of Goddard.

[12] He maintained that he could construct impromptu a sentence of up to 40 subordinate clauses "and many a native of these islands, speaking English as to the manner born, has followed me trustingly into the labyrinth only to perish miserably trying to find the way out".

[48] His knowledge and love of literature were reflected in many of his writings; among his best-known pieces is a long paragraph about the influence of Shakespeare on everyday discourse.

A relationship developed, of which she wrote after his death: "He wasn't just the big love of my life, he was a mentor as a writer and a role model as a thinker".

[56] This mirrored his opening gambit when publication of The Times resumed in 1979 after a printers' strike lasting nearly a year: his first column then had begun with the word "Moreover".

The satirical ITV show Spitting Image caricatured him in high-flown discussion with another well-known intellectual in a sketch entitled "Bernard Levin and Jonathan Miller Talk Bollocks".

[39] He had come to admire Margaret Thatcher, though not the rest of her party: "But there is one, and only one, political position that, through all the years and all my changing views and feelings, has never altered, never come into question, never seemed too simple for a complex world.

He remained true to his declared intention of eschewing all forms of vehicular transport, and walked all the way, with the exception of his crossing the Rhone, rowing himself in a small boat.

In this series he encountered extremes of wealth and poverty, and met a wide variety of people, some famous (such as Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Donald Trump) and some not (including a sword-swallowing unicyclist, and a bag lady in Central Park).

[2] A memorial service was held at the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields at which Sir David Frost delivering the eulogy described Levin as "a faithful crusader for tolerance and against injustice who had declared, 'The pen is mightier than the sword – and much easier to write with'".