Bernardino de Escalante

[5] Following his uncle Pedro, young Bernardino de Escalante entered the retinue of the future King Philip II in 1554.

[6] Soon after returning to Spain, Escalante felt that the period of European wars was over, and he also deserved a peaceful life, perhaps as a scholar or ecclesiastic.

[7] It is known that in the 1570s he enjoyed a benefice at a Laredo church, and served as the commissar of the Spanish Inquisition for the Kingdom of Galicia, often making business trips to Lisbon and Sevilla.

[7][8] At some point he was apparently transferred to Sevilla, then Spain's main port for the America trade; in 1581, he was an inquisitor in that city, and was also the majordomo of the Archbishop of Seville, Rodrigo de Castro Osorio.

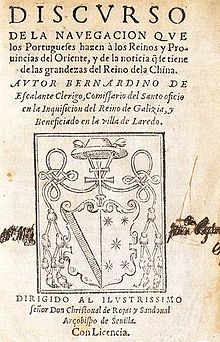

[2] Escalante's Discurso was a fairly small book, 100 folios (i.e., 200 pages in the modern system of page-counting) in octavo with wide margins.

6-16, on folios 28-99) attempt a systematic description of China - its geography, economy, culture etc., to the (rather limited) extent known at the time to the Europeans (primarily Portuguese).

[2] Unlike da Cruz's treatise, which apparently remained fairly obscure outside of Portugal, Escalante's book was quickly translated to other European languages.

The English translation, by John Frampton, appeared in 1579, under the title A discourse of the Navigation which the Portugales doe Make to the Realmes and Provinces of the East Partes of the Worlde, and of the knowledge that growes by them of the great thinges, which are in the Dominion of China.

[14][15] Escalante's sample became quite influential, primarily via the two publications that reproduced his discussion of the Chinese writing systems (including his characters): As the characters given by Escalante (and faithfully reproduced by Barbuda and Mendoza) are quite deformed, there has been a fair amount of discussion among commentators and translators of their works as to what their original form was.