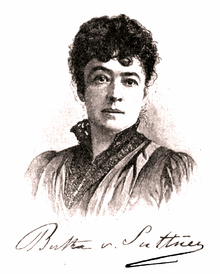

Bertha von Suttner

Through her mother, Bertha was also related to Theodor Körner, Edler von Siegringen, namesake and great-nephew of the poet, who later served as the 4th President of Austria.

[6] For the rest of her life, Bertha faced exclusion from the Austrian high nobility due to her "mixed" descent; for instance, only those with an unblemished aristocratic pedigree back to their great-great-grandparents were eligible for presentation at the imperial court.

Her older brother, Count Arthur Franz Kinsky von Wchinitz und Tettau (1827–1906), was sent to a military school at the age of six and subsequently had little contact with the family.

In 1855, Bertha's maternal aunt Charlotte (Lotte) Büschel, née von Körner (de) (also a widow), and her daughter Elvira joined the household.

[8] Beyond her reading, Bertha gained proficiency in French, Italian and English as an adolescent, under the supervision of a succession of private tutors; she also became an accomplished amateur pianist and singer.

During this trip, Bertha received a marriage proposal from Prince Philipp zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg (1836–1858), third son of Prince August Ludwig zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg (de) (Minister of State of the Duchy of Nassau) and his wife, Franziska Allesina genannt von Schweitzer (1802–1878), which was declined due to her young age.

Shortly after this, Bertha wrote her first published work, the novella Erdenträume im Monde, which appeared in Die Deutsche Frau.

Continuing poor financial circumstances led Bertha to a brief engagement to the wealthy Gustav, Baron Heine von Geldern, 31 years her senior and a member of the banking Heine family (de), whom she came to find unattractive and rejected; her memoirs record her disgusted response to the older man's attempt to kiss her.

Bertha befriended the Georgian aristocrat Ekaterine Dadiani, Princess of Mingrelia, and met Tsar Alexander II, to whom she was very distantly related.

[11][12] Seeking a career as an opera singer as an alternative to marrying into money, she undertook an intensive course of lessons, working on her voice for over four hours a day.

[16] Bertha's guardian (Landgrave Friedrich zu Fürstenberg) and her cousin Elvira both died in 1866, and she (now above the typical age of marriage) felt increasingly constrained by her mother's eccentricity and the family's poor financial circumstances.

She had an affectionate relationship with her four young students, who nicknamed her "Boulotte" (fatty) due to her size, a name she would later adopt as a literary pseudonym in the form "B.

[22] The newlywed couple eloped to Mingrelia in western Georgia, Russian Empire, near the Black Sea, where she hoped to make use of her connection to the former ruling House of Dadiani.

[19][23] Their situation worsened in 1877 on the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War, although Arthur worked as a reporter on the conflict for the Neue Freie Presse.

[24] Suttner also wrote frequently for the Austrian press in this period and worked on her early novels, including Es Löwos, a romanticised account of her life with Arthur.

[25] Arthur and Bertha von Suttner were largely socially isolated in Georgia; their poverty restricted their engagement with high society, and neither ever became fluent speakers of Mingrelian or Georgian.

In this was my peculiarly inalienable home, my refuge for all possible conditions of life, […] and so the leaves of my diary are full not only of political domestic records of all kinds, but also of memoranda of our gay little jokes, our confidential enjoyable walks, our uplifting reading, our hours of music together, and our evening games of chess.

She witnessed the foundation of the Inter-Parliamentary Union and called for the establishment of the Austrian Gesellschaft der Friedensfreunde pacifist organisation in an 1891 Neue Freie Presse editorial.

In 1897, she presented Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria with a list of signatures urging the establishment of an International Court of Justice and took part in the First Hague Convention in 1899 with the help of Theodor Herzl, who paid for her trip as a correspondent of the Zionist newspaper, Die Welt.

The many aspects of this question are what the second Hague Conference should be discussing rather than the proposed topics concerning the laws and practices of war at sea, the bombardment of ports, towns, and villages, the laying of mines, and so on.

A year later she attended the International Peace Congress in London, where she first met Caroline Playne, an English anti-war activist who would later write the first biography of Suttner.

However, the conference never took place, as she died of cancer on 21 June 1914, and seven days later the heir to her nation's throne, Franz Ferdinand was killed, triggering World War I. Suttner's pacifism was influenced by the writings of Immanuel Kant, Henry Thomas Buckle, Herbert Spencer, Charles Darwin and Leo Tolstoy (Tolstoy praised Die Waffen nieder!)

Suttner criticised this reasoning on the grounds that it placed the state as the important entity to God rather than the individual, thereby making dying in battle more glorious than other forms of death or surviving a war.

As a sign of joint solidarity, for instance, Von Suttner was a prominent participant of the 1904 'International Women's Conference' ('Internationale Frauen-Kongress') in Berlin.

Von Suttner knew, though, that conflict can only be avoided if both men and women together struggle for peace, which required an absolute belief in sex equality.

Soldiers have also to repress the compassion, the sympathy for the gigantic trouble which invades both friend and foe; for next to cowardice, what is most disgraceful to us is all sentimentality, all that is emotional.