Bertrand's postulate

In number theory, Bertrand's postulate is the theorem that for any integer

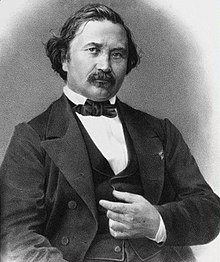

This statement was first conjectured in 1845 by Joseph Bertrand[2] (1822–1900).

Chebyshev's theorem can also be stated as a relationship with

, the prime-counting function (number of primes less than or equal to

): The prime number theorem (PNT) implies that the number of primes up to x, π(x), is roughly x/log(x), so if we replace x with 2x then we see the number of primes up to 2x is asymptotically twice the number of primes up to x (the terms log(2x) and log(x) are asymptotically equivalent).

So Bertrand's postulate is comparatively weaker than the PNT.

But PNT is a deep theorem, while Bertrand's Postulate can be stated more memorably and proved more easily, and also makes precise claims about what happens for small values of n. (In addition, Chebyshev's theorem was proved before the PNT and so has historical interest.)

The similar and still unsolved Legendre's conjecture asks whether for every n ≥ 1, there is a prime p such that n2 < p < (n + 1)2.

So, unlike the previous case of x and 2x, we do not get a proof of Legendre's conjecture for large n. Error estimates on the PNT are not (indeed, cannot be) sufficient to prove the existence of even one prime in this interval.

In greater detail, the PNT allows to estimate the boundaries for all ε > 0, there exists an S such that for x > S: The ratio between the lower bound π((x+1)2) and the upper bound of π(x2) is Note that since

More generally, these simple bounds are not enough to prove that there exists a prime between π(xn) and π((x+1)n) for any positive integer n > 1.

In 1919, Ramanujan (1887–1920) used properties of the Gamma function to give a simpler proof than Chebyshev's.

[4] His short paper included a generalization of the postulate, from which would later arise the concept of Ramanujan primes.

Other generalizations of Bertrand's postulate have been obtained using elementary methods.

(In the following, n runs through the set of positive integers.)

In 1973, Denis Hanson proved that there exists a prime between 3n and 4n.

[5] In 2006, apparently unaware of Hanson's result, M. El Bachraoui proposed a proof that there exists a prime between 2n and 3n.

[6] El Bachraoui's proof is an extension of Erdős's arguments for the primes between n and 2n.

Shevelev, Greathouse, and Moses (2013) discuss related results for similar intervals.

[7] Bertrand’s postulate over the Gaussian integers is an extension of the idea of the distribution of primes, but in this case on the complex plane.

Thus, as Gaussian primes extend over the plane and not only along a line, and doubling a complex number is not simply multiplying by 2 but doubling its norm (multiplying by 1+i), different definitions lead to different results, some are still conjectures, some proven.

[8] Bertrand's postulate was proposed for applications to permutation groups.

Sylvester (1814–1897) generalized the weaker statement with the statement: the product of k consecutive integers greater than k is divisible by a prime greater than k. Bertrand's (weaker) postulate follows from this by taking k = n, and considering the k numbers n + 1, n + 2, up to and including n + k = 2n, where n > 1.

In 1932, Erdős (1913–1996) also published a simpler proof using binomial coefficients and the Chebyshev function

[9] Erdős proved in 1934 that for any positive integer k, there is a natural number N such that for all n > N, there are at least k primes between n and 2n.

goes to infinity (and, in particular, is greater than 1 for sufficiently large

[12] In his 1998 doctoral thesis, Pierre Dusart improved the above result, showing that for

[14] In 2016, Pierre Dusart improved his result from 2010, showing (Proposition 5.4) that if

Baker, Harman and Pintz proved that there is a prime in the interval

[17] Dudek also proved that the Riemann hypothesis implies that for all