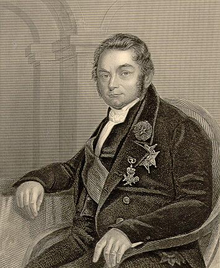

Jöns Jacob Berzelius

[2] Berzelius is considered, along with Robert Boyle, John Dalton, and Antoine Lavoisier, to be one of the founders of modern chemistry.

[4] Although Berzelius began his career as a physician, his enduring contributions were in the fields of electrochemistry, chemical bonding and stoichiometry.

Berzelius demonstrated the use of an electrochemical cell to decompose certain chemical compounds into pairs of electrically opposite constituents.

From this research, he articulated a theory that came to be known as electrochemical dualism, contending that chemical compounds are oxide salts, bonded together by electrostatic interactions.

[5] Berzelius's work with atomic weights and his theory of electrochemical dualism led to his development of a modern system of chemical formula notation that showed the composition of any compound both qualitatively and quantitatively.

His father Samuel Berzelius was a school teacher in the nearby city of Linköping, and his mother Elizabeth Dorothea Sjösteen was a homemaker.

His father died in 1779, after which his mother married a pastor named Anders Eckmarck, who gave Berzelius a basic education including knowledge of the natural world.

[10] As a teenager, he took a position as a tutor at a farm near his home, during which time he became interested in collecting flowers and insects and their classification.

He constructed a similar battery for himself, consisting of alternating disks of copper and zinc, and this was his initial work in the field of electrochemistry.

At this time, the Academy had been stagnating for several years, since the era of romanticism in Sweden had led to less interest in the sciences.

During Berzelius' tenure, he is credited with revitalising the Academy and bringing it into a second golden era (the first being the astronomer Pehr Wilhelm Wargentin's period as secretary from 1749 to 1783).

[16] Berzelius wrote the foreword to one of Carl af Ekenstam's [sv] works on the topic, of which 50,000 copies were printed.

[10] Soon after arriving in Stockholm, Berzelius wrote a chemistry textbook for his medical students, Lärbok i Kemien, which was his first significant scientific publication.

He had conducted experimentation, in preparation for writing this textbook, on the compositions of inorganic compounds, which was his earliest work on definite proportions.

[21][22] The essay ended with a table of the "specific weights" (relative atomic masses) of the elements, where oxygen was set to 100, and a selection of compounds written in his new formalism.

[26]: 682–683 Berzelius's last revised version of his atomic weight tables was first published in a German translation of his Textbook of Chemistry in 1826.

[28] Berzelius is credited with discovering the chemical elements cerium and selenium and with being the first to isolate silicon, thorium, titanium and zirconium.

Berzelius recognized this powder as the new element of silicon, which he called silicium,[35] a name proposed earlier by Davy.

In particular, he advised Gerardus Johannes Mulder in his elemental analyses of organic compounds such as coffee, tea, and various proteins.

The term is derived from the Greek, meaning "of the first rank", and Berzelius proposed the name because proteins were so fundamental to living organisms.

In 1812, Berzelius traveled to London, England, including Greenwich to meet with prominent British scientists of the time.

These findings persuaded Berzelius that not all acids contain oxygen, and that Davy and Gay-Lussac were correct: chlorine and iodine are indeed elements.

[48] The Royal Society of London gave Berzelius the Copley Medal in 1836 with the citation "For his systematic application of the doctrine of definite proportions to the analysis of mineral bodies, as contained in his Nouveau Systeme de Mineralogie, and in other of his works.

Invitees at the ceremony marking the occasion included scientific dignitaries from eleven European nations and the United States, many of whom gave formal addresses in honor of Berzelius.

[8] In 1939 his portrait appeared on a series of postage stamps commemorating the bicentenary of the founding of the Swedish Academy of Sciences.