Beslan school siege

[8] Criticisms of the Russian government's management of the crisis have persisted, including allegations of disinformation and censorship in news media as well as questions about journalistic freedom,[9] negotiations with the terrorists, allocation of responsibility for the eventual outcome and the use of excessive force.

Early in the morning, a group of several dozen heavily armed Islamic nationalist guerrillas left a forest encampment located in the vicinity of the village of Psedakh in the neighbouring Republic of Ingushetia, east of North Ossetia and west of war-torn Chechnya.

[22] Gurazhev was left in a vehicle after the terrorists had reached Beslan and then ran toward the schoolyard[23] and went to the district police department to inform them of the situation, adding that his duty handgun and badge had been taken.

[34][35][36][37][38] Karen Mdinaradze, the FC Alania team cameraman, survived the explosion as well as the shooting; when discovered to be still alive, he was allowed to return to the sports hall, where he lost consciousness.

[10][43] The Russian government announced that it would not use force to rescue the hostages, and negotiations toward a peaceful resolution took place on the first and second days, at first led by Leonid Roshal, a pediatrician whom the hostage-takers had reportedly requested by name.

[47] On 2 September 2004, negotiations between Roshal and the militants proved unsuccessful, and they refused to allow food, water or medicine to be taken in for the hostages or for the dead bodies to be removed from the front of the school.

[52] Only on the second day did Putin make his first public comment on the siege during a meeting in Moscow with King Abdullah II of Jordan: "Our main task, of course, is to save the lives and health of those who became hostages.

By the time that he left Moscow on the second day, Aslakhanov had accumulated the names of more than 700 well-known Russian figures who were volunteering to enter the school as hostages in exchange for the release of the children.

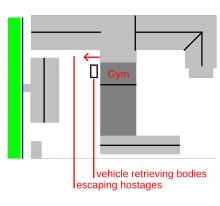

[16] According to a military prosecutor, a BTR armoured vehicle drove close to the school and opened fire from its 14.5×114mm KPV heavy machine gun at the windows on the second floor.

[141] He condemned the action and all attacks against civilians via a statement issued by his envoy Akhmed Zakayev in London, blaming it on what he called a radical local group,[142] and he agreed to the North Ossetian proposition to act as a negotiator.

[154] Witness testimonies during the Kulayev trial reported the presence of a number of apparently Slavic-, unaccented Russian- and "perfect" Ossetian-speaking individuals among the militants who were not seen among the bodies of those killed by Russian security forces.

The forensic tests also established that 21 of the hostage-takers took heroin,[157] methamphetamine as well as morphine in a normally lethal amount;[158][159] the investigation cited the use of drugs as a reason for the militants' ability to continue fighting despite being badly wounded and presumably in great pain.

The state-controlled Channel One showed fragments of Kulayev's interrogation in which he said his group was led by a Chechnya-born man nicknamed Polkovnik and by the North Ossetia native Vladimir Khodov.

[188] At a press conference with foreign journalists on 6 September 2004, Vladimir Putin rejected the prospect of an open public inquiry, but cautiously agreed with an idea of a parliamentary investigation led by the State Duma, dominated by the pro-Kremlin parties.

"[194] Ella Kesayeva, an activist who leads a Beslan support group, suggested that the report was meant as a signal that Putin and his circle were no longer interested in having a discussion about the crisis.

According to Savelyev, a weapons and explosives expert, special forces fired rocket-propelled grenades without warning as a prelude to an armed assault, ignoring apparently ongoing negotiations.

[197] In June 2007, a court in Kabardino-Balkaria charged two Malgobeksky District ROVD police officials, Mukhazhir Yevloyev and Akhmed Kotiyev, with negligence, accusing them of failing to prevent the attackers from setting up their training and staging camp in Ingushetia.

[10][212] According to Basayev, the road to Beslan was cleared of roadblocks because the FSB planned to ambush the group later, believing the terrorists' aim was to seize the parliament of North Ossetia in Vladikavkaz.

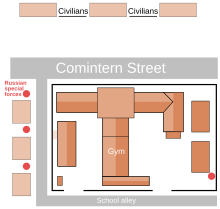

Critics also charged that the authorities did not organise the siege properly, including failing to keep the scene secure from entry by civilians,[213] while the emergency services were not prepared during the 52 hours of the crisis.

[clarification needed] Two months after the crisis, human remains and identity documents were found by a local driver, Muran Katsanov,[11] in the garbage landfill at the outskirts of Beslan; the discovery prompted further outrage.

The report by Yuri Savelyev, a dissenting parliamentary investigator and one of Russia's leading rocket scientists, placed the responsibility for the final massacre on actions of the Russian forces and the highest-placed officials in the federal government.

[219] Result were published in April 2017, and found that Russian actions in using tank cannons, flame-throwers and grenade launchers "contributed to the casualties among the hostages", and had "not been compatible with the requirement under Article 2 that lethal force be used "no more than [is] absolutely necessary".

"[99]The Moscow daily tabloid Moskovskij Komsomolets ran a rubric headlined "Chronicle of Lies", detailing various initial reports put out by government officials about the hostage taking, which later turned out to be false.

[99][226] According to the report by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), several correspondents were detained or otherwise harassed after arriving in Beslan (including Russians Anna Gorbatova and Oksana Semyonova from Novye Izvestia, Madina Shavlokhova from Moskovskij Komsomolets, Elena Milashina from Novaya Gazeta, and Simon Ostrovskiy from The Moscow Times).

Many foreign journalists were exposed to pressure from the security forces and materials were confiscated from TV crews ZDF and ARD (Germany), AP Television News (US), and Rustavi 2 (Georgia).

[234][235] The graphic film apparently shows the prosecutors and military experts surveying the unexploded shrapnel-based bombs of the militants and structural damage in the school in Beslan shortly after the massacre.

President Vladimir Putin specifically dismissed the foreign criticism as Cold War mentality and said that the West wants to "pull the strings so that Russia won't raise its head.

[13] To address doubts, in 2005 Putin launched a Duma parliamentary investigation led by Aleksandr Torshin,[239] resulting in the report which criticised the federal government only indirectly[240] and instead put blame for "a whole number of blunders and shortcomings" on local authorities.

[248] In July 2007, the office of the presidential envoy for the Southern Federal District Dmitry Kozak announced that a North Ossetian armed group engaged in abductions as retaliation for the Beslan school hostage-taking.

[251] In January 2008, the Voice of Beslan group, which in the previous year had been court-ordered to disband, was charged by Russian prosecutors with "extremism" for their appeals in 2005 to the European Parliament to help establish an international investigation.