Betelgeuse

With a radius between 640 and 764 times that of the Sun,[14][11] if it were at the center of our Solar System, its surface would lie beyond the asteroid belt and it would engulf the orbits of Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars.

[34] From Arctic latitudes, Betelgeuse's red colour and higher location in the sky than Rigel meant the Inuit regarded it as brighter, and one local name was Ulluriajjuaq ("large star").

The 1950s and 1960s saw two developments that affected stellar convection theory in red supergiants: the Stratoscope projects and the 1958 publication of Structure and Evolution of the Stars, principally the work of Martin Schwarzschild and his colleague at Princeton University, Richard Härm.

Baldwin and colleagues of the Cavendish Astrophysics Group, the new technique employed a small mask with several holes in the telescope pupil plane, converting the aperture into an ad hoc interferometric array.

The "bright patches" or "hotspots" observed with these instruments appeared to corroborate a theory put forth by Schwarzschild decades earlier of massive convection cells dominating the stellar surface.

[54] In a study published in December 2000, the star's diameter was measured with the Infrared Spatial Interferometer (ISI) at mid-infrared wavelengths producing a limb-darkened estimate of 55.2±0.5 mas – a figure entirely consistent with Michelson's findings eighty years earlier.

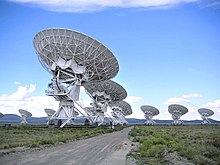

Images released by the European Southern Observatory in July 2009, taken by the ground-based Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI), showed a vast plume of gas extending 30 AU from the star into the surrounding atmosphere.

Hubble captured signs of dense, heated material moving through the star's atmosphere in September, October and November before several telescopes observed the more marked dimming in December and the first few months of 2020.

[63][64][65] By January 2020, Betelgeuse had dimmed by a factor of approximately 2.5 from magnitude 0.5 to 1.5 and was reported still fainter in February in The Astronomer's Telegram at a record minimum of +1.614, noting that the star is currently the "least luminous and coolest" in the 25 years of their studies and also calculating a decrease in radius.

The photosphere has an extended atmosphere, which displays strong lines of emission rather than absorption, a phenomenon that occurs when a star is surrounded by a thick gaseous envelope (rather than ionized).

[97] As the researcher, Harper, points out: "The revised Hipparcos parallax leads to a larger distance (152±20 pc) than the original; however, the astrometric solution still requires a significant cosmic noise of 2.4 mas.

[10] In 2020, new observational data from the space-based Solar Mass Ejection Imager aboard the Coriolis satellite and three different modeling techniques produced a refined parallax of 5.95+0.58−0.8 mas, a radius of 764+116−62 R☉, and a distance of 168.1+27.5−14.4 pc or 548+90−49 ly, which would imply Betelgeuse is nearly 25% smaller and 25% closer to Earth than previously thought.

Astronomical interferometry, first conceived by Hippolyte Fizeau in 1868, was the seminal concept that has enabled major improvements in modern telescopy and led to the creation of the Michelson interferometer in the 1880s, and the first successful measurement of Betelgeuse.

[119] Other technological breakthroughs include adaptive optics,[120] space observatories like Hipparcos, Hubble and Spitzer,[51][121] and the Astronomical Multi-BEam Recombiner (AMBER), which combines the beams of three telescopes simultaneously, allowing researchers to achieve milliarcsecond spatial resolution.

[144] A series of spectropolarimetric observations obtained in 2010 with the Bernard Lyot Telescope at Pic du Midi Observatory revealed the presence of a weak magnetic field at the surface of Betelgeuse, suggesting that the giant convective motions of supergiant stars are able to trigger the onset of a small-scale dynamo effect.

[97][148] Starting from its present position and motion, a projection back in time would place Betelgeuse around 290 parsecs farther from the galactic plane—an implausible location, as there is no star formation region there.

Originally a member of a high-mass multiple system within Ori OB1a, Betelgeuse was probably formed about 10–12 million years ago,[151] but has evolved rapidly due to its high mass.

[152] In the late phase of stellar evolution, massive stars like Betelgeuse exhibit high rates of mass loss, possibly as much as one M☉ every 10,000 years, resulting in a complex circumstellar environment that is constantly in flux.

[50] Recent work has corroborated this hypothesis, yet there are still uncertainties about the structure of their convection, the mechanism of their mass loss, the way dust forms in their extended atmosphere, and the conditions which precipitate their dramatic finale as a type II supernova.

[129] In 2001, Graham Harper estimated a stellar wind at 0.03 M☉ every 10,000 years,[154] but research since 2009 has provided evidence of episodic mass loss making any total figure for Betelgeuse uncertain.

"[158] This is the same region in which Kervella's 2009 finding of a bright plume, possibly containing carbon and nitrogen and extending at least six photospheric radii in the southwest direction of the star, is believed to exist.

[18] Betelgeuse's time spent as a red supergiant can be estimated by comparing mass loss rates to the observed circumstellar material, as well as the abundances of heavy elements at the surface.

[177] Due to misunderstandings caused by the 2009 publication of the star's 15% contraction, apparently of its outer atmosphere,[56][125] Betelgeuse has frequently been the subject of scare stories and rumors suggesting that it will explode within a year, and leading to exaggerated claims about the consequences of such an event.

CNN, for example, chose the headline "A giant red star is acting weird and scientists think it may be about to explode",[187] while the New York Post declared Betelgeuse as "due for explosive supernova".

One study found that a not yet directly-observed, dust-modulating star or white dwarf of 1.17±0.07 M☉ at a distance of 8.60±0.33 AU would be the most likely solution for Betelgeuse's 2170-day secondary periodicity, fluctuating radial velocity, moderate radius and low variation in effective temperature.

[193] A second study produced by a different group of researchers examined observational data spanning a century, also suggesting a close-in stellar companion, possibly less massive and luminous than the Sun with an orbital period of 5.78 years.

[31] Aboriginal people from the Great Victoria Desert of South Australia incorporated Betelgeuse into their oral traditions as the club of Nyeeruna (Orion), which fills with fire-magic and dissipates before returning.

[209][210] The Wardaman people of northern Australia knew the star as Ya-jungin ("Owl Eyes Flicking"), its variable light signifying its intermittent watching of ceremonies led by the Red Kangaroo Leader Rigel.

[214] To the Inuit, the appearance of Betelgeuse and Bellatrix high in the southern sky after sunset marked the beginning of spring and lengthening days in late February and early March.

The star's unusual name inspired the title of the 1988 film Beetlejuice, referring to its titular antagonist, and script writer Michael McDowell was impressed by how many people made the connection.