Betsy Bakker-Nort

Bertha "Betsy" Bakker-Nort (8 May 1874 – 23 May 1946) was a Dutch lawyer and politician who served as a member of the House of Representatives for the Free-thinking Democratic League (VDB) from 1922 to 1942.

Born in Groningen, she became involved with the feminist movement in 1894, joining the Dutch Association for Women's Suffrage (VVVK), where she was mentored by Aletta Jacobs, one of the pioneering activists of the 19th century.

[2] She later said that, as a young girl, it struck her as unfair that her independent mother was not allowed to vote in local council elections, "yet each man was, no matter how dumb".

[11] In 1899 Nort started writing about women's issues, drawing upon her Scandinavian experience; her early work was published as columns in the feminist magazine Belang en Recht ("The Importance of the Law").

[1] In 1908, at age 34, Bakker-Nort started studying law at the University of Groningen after realising that the fight for women's rights required comprehensive legal knowledge.

[8] Unable to restrict herself to comparisons, she added a reasoned plea for abolishing the part of the marital law that declared married women "incompetent to act".

As described in the 1838 civil code, the status of married women was legally similar to that of minors and people with severe mental health problems.

[17][A] This meant that married women could not open a bank account, apply for a mortgage or insurance, or sign a labour agreement without their husbands' permission.

[12] Bakker-Nort considered getting women the right to vote to be a principal means to achieve the overhaul of marriage law, a standard view among first wave feminists.

[24] She joined the Association of Women with Higher Education [nl] (VVAO), a more conservative group than the VVVK which did not always appreciate her progressive ideas and, for example, did not include her in their legal committee, despite her expertise.

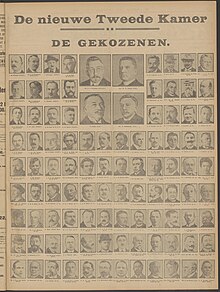

[28] In the 1918 general elections, the VDB reserved two spots for women on their candidate list and assigned them to Bakker-Nort and her mentor Jacobs.

[12] In her first year, Bakker-Nort introduced a bill for a so-called "sister-pension", to entitle sisters who had lived with and looked after widowed brothers to the right to their pension once they died.

However, in 1928, Bakker-Nort again made a plea in parliament to end the legal incompetency of married women, but it was rejected by the Christian majority.

However, her optimism soon disappeared when the Great Depression led to fast-rising unemployment, and married women were fired to make way for male job-seekers.

[45][46] The women staged protest marches, carrying their national flags and wearing dresses ranging from white (equality) to black (absolutely unequal).

[45][46] The activists were able to get meetings with the League of Nations delegates but eventually antagonised the conference president so much that he ordered the police to remove the women from the Peace Palace.

[6][7][51] In 1933 Bakker-Nort accepted an invitation from German communist leader Willi Münzenberg to travel to London and join an international commission of foreign legal experts participating in a counter-trial of the arson case of the Reichstag fire.

Bakker-Nort argued that because it was impossible to determine who was Jewish and who was Aryan, the rules of the treaty did not apply, and the Dutch would not have to revoke the convention's agreement.

[60] In 1937 Bakker-Nort wrote a piece about fascism in the election issue of the VDB's monthly magazine entitled "Democracy or Dictatorship", in which she attacked the fascist party the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (NSB) in an unusually sarcastic way.

[63] The election results did not disappoint Bakker-Nort; she said voters had not punished the VDB and had understood why the party had to allow some women's rights to erode.

They were spurred on by the activities of the VVGS, whose youth committee's president Tendeloo and other feminists such as Willemijn Posthumus-van der Goot organised protests across the country.

[66] In a later debate on labour issues, Bakker-Nort asked the government to address the widespread sexual harassment to which female factory workers were subjected.

[12][76] Bakker-Nort had spent eighteen years in the House, addressing parliament mainly on the issues of justice, education, and labour, and for the majority of her stay, was on the Standing Committee for Private and Criminal Law.

[6][7] As the German occupiers started to arrest and deport some Jewish Dutch citizens in the summer of 1940, Bakker-Nort must have felt threatened, according to Klijnsma.

[79][80] However, in April 1944, the Germans moved all Jews from Barneveld back to Westerbork and then in September 1944 onwards to the Theresienstadt concentration camp in Bohemia in what is now the Czech Republic.

[7] While the national newspaper Algemeen Handelsblad published only a short notice of her death, Tendeloo and former VDB chairman Pieter Oud wrote obituaries.

[85] In his 1968 memoirs, Oud wrote that her dedication to public office was equal to none and that although he did not consider her oratory skills the best, she quickly became a competent parliamentarian through her high work rate.

[82] Braun wrote in 2013 that in the 21st century, Bakker-Nort is seen as a transition figure who was part of the first wave of feminism in the Netherlands that got women the vote but continued the fight for more rights.

Once women's suffrage was achieved, the strength of activism had significantly reduced: member numbers for groups such as the VVS dwindled.

Despite the political climate in the 1920s and 1930s being dominated by Christian parties that aimed to reduce women's rights based on their interpretation of the Bible, Bakker-Nort's efforts, in and outside parliament, were relentless.