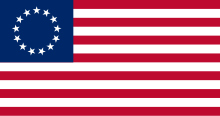

Betsy Ross

[7] Mrs. Ross convinced George Washington to change the shape of the stars in a sketch of a flag he showed her from six-pointed to five-pointed by demonstrating that it was easier and speedier to cut the latter.

As late as October 1776, Captain William Richards was still writing to the Committee of Safety to request the design that he could use to order flags for the fleet.

[13] It is worded as follows: An order on William Webb to Elizabeth Ross for fourteen pounds twelve shillings and two pence for Making Ships Colours [etc.]

[22] In 1870, Ross's grandson, William J. Canby, presented a research paper to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in which he claimed that his grandmother had "made with her hands the first flag" of the United States.

Canby dates the historic episode based on Washington's journey to Philadelphia, in the late spring of 1776, a year before the Second Continental Congress passed the first Flag Act of June 14, 1777.

Betsy Ross was promoted as a patriotic role model for young girls and a symbol of women's contributions to American history.

[25] American historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich further explored this line of enquiry in a 2007 article, "How Betsy Ross Became Famous: Oral Tradition, Nationalism, and the Invention of History".

The young couple soon started their own upholstery business and later joined Christ Church, where their fellow congregants occasionally included visiting colony of Virginia militia regimental commander, colonel, and soon-to-be-general George Washington (of the newly organized Continental Army) and his family from their home Anglican parish of Christ Church in Alexandria, Virginia, near his Mount Vernon estate on the Potomac River, along with many other visiting notaries and delegates in future years to the soon-to-be-convened Continental Congress and the political/military leadership of the colonial rebellion.

As a member of the local Pennsylvania Provincial Militia and its units from the city of Philadelphia, John Ross was assigned to guard munitions.

[31] The 24-year-old Elizabeth ("Betsy") continued working in the upholstery business repairing uniforms and making tents, blankets, and stuffed paper tube cartridges with musket balls for prepared packaged ammunition in 1779 for the Continental Army.

In 1780, Ashburn's ship was captured by a Royal Navy frigate and he was charged with treason (for being of British ancestry—naturalization to American colonial citizenship was not recognized) and imprisoned at Old Mill Prison in Plymouth, England.

[20] Three years later, in May 1783, she married John Claypoole, who had earlier met Joseph Ashburn in the English Old Mill Prison and had informed Ross of her husband's circumstances and death.

With the birth of their second daughter Susanna in 1786, they moved to a larger house on Philadelphia's Second Street, settling down to a peaceful post-war existence, as Philadelphia prospered as the temporary national capital (1790–1800) of the newly independent United States of America, with the first president, George Washington, his vice president, John Adams, and the convening members of the new federal government and the U.S. Congress.

In 1793, her mother, father, and sister Deborah Griscom Bolton (1743–1793) all died in another severe epidemic of yellow fever, a disease found in the 19th century to be spread by infected mosquitoes.

Ross, by then completely blind, spent her last three years living with her middle Claypoole daughter Jane (1792–1873) in Philadelphia, which was rapidly growing and industrializing.

In 1856, the remains of Ross and her third husband John Claypoole were moved from the Free Quaker Burying Ground to Mount Moriah Cemetery.

Bones found elsewhere in the family plot were deemed to be hers and were reinterred in the current grave visited by tourists at the Betsy Ross House.

Biographer Marla Miller argues that Ross' legacy should not be about a single flag, but rather what her story tells us about working women and men during the American Revolution.