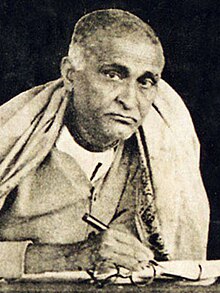

Bhaktivinoda Thakur

[5] In his later years Bhaktivinoda founded and conducted nama-hatta – a travelling preaching program that spread theology and practice of Chaitanya throughout rural and urban Bengal, by means of discourses, printed materials and Bengali songs of his own composition.

[8] Bhaktivinoda Thakur led the spread of Chaitanya's teachings in the West,[4] in 1880 sending copies of his works to Ralph Waldo Emerson in the United States and to Reinhold Rost in Europe.

[9] Bhaktisiddhanta's disciple A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami (1896–1977) continued his guru's Western mission when in 1966 in the United States he founded ISKCON, or the Hare Krishna movement, which then spread Gaudiya Vaishnavism globally.

[10] The bhadralok, refers to "gentle or respectable people",[11] was a class of Bengalis (Hindus), who served the British administration in occupations requiring Western education and proficiency in English and other languages.

[4][12] Exposed to and influenced by the Western values of the British, including the latter's condescending attitude towards cultural and religious traditions of India, the bhadralok started calling into question and reassessing the tenets of their own religion and customs.

[14][15][16] This trend led to a perception, both in India and in the West, of modern Hinduism as being equivalent to Advaita Vedanta, a conception of the divine as devoid of form and individuality that was hailed by its proponents as the "perennial philosophy"[17] and "the mother of religions".

[18] As a result, the other schools of Hinduism, including bhakti, were gradually relegated in the minds of the Bengali Hindu middle-class to obscurity, and seen as a "reactionary and fossilized jumble of empty rituals and idolatrous practices.

[21] Kedaranath in his autobiography Svalikhita-jivani refers to his father, Anand Chandra Dutta, as a "straightforward, clean, religious man"[22] and describes his mother as "a sober woman possessed of many unique qualities".

[19] Prior to his birth, financial circumstances had forced his parents to relocate from Calcutta to Ula, where he was born and grew up in the palace of his maternal grandfather, Ishwar Chandra Mustauphi, a landowner known for his generosity.

The financial situation of his widowed mother worsened as his maternal grandfather, Ishwar Chandra, incurred huge debts due to the oppressive Permanent Settlement Act and ended up bankrupt.

Finally, in 1852 his maternal uncle, Kashiprasad Ghosh, a famous poet and newspaper editor, visited Ula and, impressed with the talented boy, convinced Jagat Mohini to send Kedarnath to Calcutta to further his studies.

[34] Exposed to and influenced by the views of the acquaintances of Kashiprasad who frequented his home, Kristo Das Pal, Shambhu Mukhopadhyay, Baneshwar Vidyalankar, and others – Kedarnath started regularly contributing to the Hindu Intelligencer, critiquing contemporary social and political issues from a bhadralok viewpoint.

Along with Dvijendranath Tagore, Kedarnath started studying Sanskrit and the theological writings of such authors as Kant, Goethe, Hegel, Swedenborg, Hume, Voltaire, and Schopenhauer, as well as the books of the Brahmo Samaj, which rekindled his interest in Hinduism.

[47] After a few unsuccessful stints as a teacher and after incurring a debt, Kedarnath along with his mother and wife accepted the invitation of Rajballabh, his paternal grandfather in Orissa, and in the spring of 1858 left for the Orissan village of Chutimangal.

[49] This established Kedarnath as an intellectual and cultural voice of the local bhadralok community, and soon a following of his own formed, consisting of students attracted by his discourses and personal tutorship on religious and philosophical topics.

[74] When Kedarnath suffered from prolonged bouts of fever and colitis,[e] he took advantage of the paid sick leave to visit Mathura and Vrindavana – sacred places for Gaudiya Vaishnavas.

[81] Following the annexation of the state of Orissa by Britain in 1803, the British force commander in India, Marquess Wellesley, ordered by decree "the utmost degree of accuracy and vigilance" in protecting the security of the Jagannath temple and in respecting religious sentiments of its worshipers.

[92] The same account mentions that at his birth, the child's umbilical cord was looped around his body like a sacred brahmana thread (upavita) that left a permanent mark on the skin, as if foretelling his future role as religious leader.

By the end Kedarnath's tenure in Puri his family had seven children, and his oldest daughter, Saudamani, 10, had to be married – which, according to upper-class Hindu customs, had to take place in Bengal.

[114][6] From 1874 till his departure in 1914 Bhaktivinoda wrote, both philosophical works in Sanskrit and English that appealed to the bhadralok intelligentsia, and devotional songs (bhajans) in simple Bengali that conveyed the same message to the masses.

[115] His bibliography counts over one hundred works, including his translations of canonical Gaudiya Vaishnava texts, often with his own commentaries, as well as poems, devotional song books, and essays[116][115] – an achievement his biographers attribute in large part to his industrious and organised nature.

[118][119] Composed in Sanskrit and Bengali, the book was intended as a response to criticism of Krishna by Christian missionaries, Brahmo Samaj, and Westernised bhadralok for what they saw as his immoral, licentious behavior incompatible with his divine status in Hinduism.

[118] In defense of the tenets of Vaishnavism, Bhaktivinoda's Krishna-samhita employed the same rational tools of its opponents, complete with contemporary archeological and historical data and theological thought, to establish Krishna's pastimes as transcendent (aprakrita) manifestations of morality.

[120]Undaunted by the criticism, Bhaktivinoda saw Krishna-samhita as an adequate presentation of the Gaudiya Vaishnava thought even for a Western mind and in 1880 sent copies of the book to leading intellectuals of Europe and America.

[126] In Jaiva-dharma, another key work, published in 1896,[127] Bhaktivinoda employs the fictional style of a novel to create an ideal, even utopian Vaishnava realm that serves as a backdrop to philosophical and esoteric truths unfolding in a series of conversations between the book's characters and guiding their devotional transformations.

The work described a life full of financial struggle, health issues, internal doubts and insecurity, and introspection that gradually led him, sometimes in convoluted ways, to the deliberate and mature decision of accepting Chaitanya Mahaprabhu's teachings as his final goal.

[154] Gradually Bhaktivinoda directed criticism at various heterodox Vaishnava groups abounding in Bengal that he identified and termed "a-Vaishnava" (non-Vaishnava) and apasampradayas ("deviant lineages"): Aul, Baul, Saina, Darvesa, Sahajiya, smarta brahmanas, etc.

[157] A more tacit but nothing short of uncompromising philosophical assault was directed at the influential jati-gosais (caste goswamis) and smarta brahmanas who claimed exclusive right to conduct initiations into Gaudiya Vaishnavism on the basis of their hereditary affiliation with it and denied eligibility to do so to non-brahmana Vaishnavas.

[162]Bhaktivinoda adapted his message to the Western mind by borrowing popular Christian expressions such as "universal fraternity", "cultivation of the spirit", "preach", and "church" and deliberately using them in a Hindu context.

[166][167] Modeled after the original Gaudiya Math and emulating its emphasis on dynamic mission and spiritual practice, ISKCON popularised Chaitanya Vaishnavism on a global scale, becoming the world's leading proponent of Hindu bhakti personalism.

Second row: Kamala Prasad, Shailaja Prasad, unknown grandchild, and Hari Pramodini.

Front row: two unknown grandchildren.