Biafran airlift

The Biafran Airlift was an international humanitarian relief effort that transported food and medicine to Biafra during the Nigerian Civil War.

This sustained joint effort, which lasted one and a half times as long as its Berlin predecessor, is estimated to have saved more than a million lives.

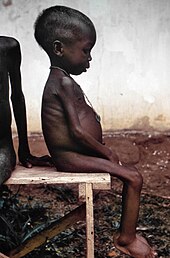

"[5] With the advent of global television reporting, for the first time, famine, starvation, and the humanitarian response were seen by millions around the world, demanding that both the government and private sector joint efforts to save as many as possible from starving to death.

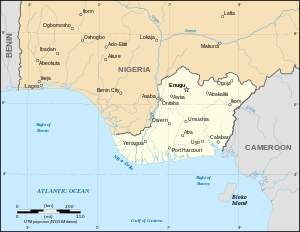

[6] The position of the Organization of African Unity was to not intervene in conflicts its members' deemed internal and to support the nation-state boundaries instituted during the colonial era.

[7] The ruling Labour Party of the United Kingdom, which together with the USSR was supplying arms to the Nigerian military,[8] dismissed reports of famine as "enemy propaganda".

[9] Mark Curtis writes that the UK also reportedly provided military assistance on the 'neutralisation of the rebel airstrips', with the understanding that their destruction would put them out of use for daylight humanitarian relief flights.

The Joint Church Airlift (JCA) provided relief aid as well as attempted to establish an air force for Biafra.

Bernard Kouchner, a French doctor and one of the more outspoken critics, declared that this silence over Biafra made the ICRC's workers "accomplices in the systematic massacre of a population".

[14] Canada, facing its own internal separatist threat in the form of the Quebec sovereignty movement, was reluctant to extend aid to an area trying to separate from a fellow Commonwealth member, particularly in a region in which it had no prior experience.

[16] Relief aid into Biafra began arriving by land, sea, and air soon after the start of the Nigerian Civil War in 1967.

"[18][19] A leading critic of the ICRC's position declared that their silence over Biafra made its workers accomplices in the systematic massacre of a population.

The committee included Caritas Internationalis, World Council of Churches, Catholic Relief Services, and Nordchurchaid (a collective of Scandinavian Protestant groups).

Almost all of the airplanes, crews and logistics were paid, set up and maintained by the joint churches through contracted companies and volunteers on the ground.

[29] In late 1968, before the arrival of the C-97s from the US, (VERIFY) an estimated 15–20 flights each night were made into Biafra: 10–12 from Sao Tome (JCA, Canairelief, and others), 6–8 from Fernando Po (mostly ICRC), and 3–4 from Libreville, Gabon (mostly French).

Some pilots agreed to carry cargo that could be hazardous to the aircraft: fuel for cooking and ground transport (flammable), and salt (corrosive).

Most others were volunteers, performing tasks for which they had no little or no training or prior experience, from loading and unloading, warehouse, inventory, to aircraft maintenance and engine mechanics.

[32] Most of the aircraft were operated or contracted by "Joint Church Aid", often referred to as "Jesus Christ Airlines" from the initials JCA, flying primarily from Sao Tome and Cotonou.

Military transports such as second-hand US Boeing C-97 Stratofreighters,[26] a C-130E Hercules from the Canadian Armed Forces,[6] and a Transall C.160 provided by Germany were also loaned to the effort.

At least 29 pilots and crew from the relief agencies were killed by accidents or by Nigerian forces in 10 separate incidents during the airlift: 25 from JCA, 4 from Canairelief, and 3 from the ICRC.

[37][1] Approximately 30 non-governmental organizations and several governments provided non-military direct and indirect aid through or in support of the Biafran Airlift.

Subsequent famine relief efforts in places such as Ethiopia, Somalia, or the former Yugoslavia by world governments were not met with the same response as with Biafra.