Panchatantra

Its range has extended from Java to Iceland... [In India,] it has been worked over and over again, expanded, abstracted, turned into verse, retold in prose, translated into medieval and modern vernaculars, and retranslated into Sanskrit.

And most of the stories contained in it have "gone down" into the folklore of the story-loving Hindus, whence they reappear in the collections of oral tales gathered by modern students of folk-stories.The earliest known translation, into a non-Indian language, is in Middle Persian (Pahlavi, 550 CE) by Burzoe.

[13] Rendered in prose by Abu'l-Ma'ali Nasrallah Monshi in 1143 CE, this was the basis of Kashefi's 15th-century Anvār-i Suhaylī (The Lights of Canopus),[14] which in turn was translated into Humayun-namah in Turkish.

It is unclear, states Patrick Olivelle, a professor of Sanskrit and Indian religions, if Vishnusharma was a real person or himself a literary invention.

Though the text is now known as Panchatantra, the title found in old manuscript versions varies regionally, and includes names such as Tantrakhyayika, Panchakhyanaka, Panchakhyana and Tantropakhyana.

[24] According to Gillian Adams, Panchatantra may be a product of the Vedic period, but its age cannot be ascertained with confidence because "the original Sanskrit version has been lost".

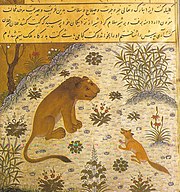

[36] The Book 1 contains over thirty fables, with the version Arthur Ryder translated containing 34: The Loss of Friends, The Wedge-Pulling Monkey, The Jackal and the War-Drum, Merchant Strong-Tooth, Godly and June, The Jackal at the Ram-Fight, The Weaver's Wife, How the Crow-Hen Killed the Black Snake, The Heron that Liked Crab-Meat, Numskull and the Rabbit, The Weaver Who Loved a Princess, The Ungrateful Man, Leap and Creep, The Blue Jackal, Passion and the Owl, Ugly's Trust Abused, The Lion and the Carpenter, The Plover Who Fought the Ocean, Shell-Neck Slim and Grim, Forethought Readywit and Fatalist, The Duel Between Elephant and Sparrow, The Shrewd Old Gander, The Lion and the Ram, Smart the Jackal, The Monk Who Left His Body Behind, The Girl Who Married a Snake, Poor Blossom, The Unteachable Monkey, Right-Mind and Wrong-Mind, A Remedy Worse than the Disease, The Mice That Ate Iron, The Results of Education, The Sensible Enemy, The Foolish Friend.

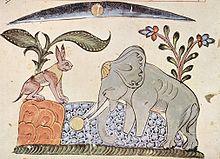

[38] The second book contains ten fables: The Winning of Friends, The Bharunda Birds, Gold's Gloom, Mother Shandilee's Bargain, Self-defeating Forethought, Mister Duly, Soft, the Weaver, Hang-Ball and Greedy, The Mice That Set Elephant Free, Spot's Captivity.

[37] The third treatise discusses war and peace, presenting through animal characters a moral about the battle of wits being a strategic means to neutralize a vastly superior opponent's army.

[43] The fourth book contains thirteen fables in Ryder translation: Loss of Gains, The Monkey and the Crocodile, Handsome and Theodore, Flop-Ear and Dusty, The Potter Militant, The Jackal Who Killed No Elephants, The Ungrateful Wife, King Joy and Secretary Splendor, The Ass in the Tiger-Skin, The Farmer's Wife, The Pert Hen-Sparrow, How Supersmart Ate the Elephant, The Dog Who Went Abroad.

[45] The fifth book contains twelve fables about hasty actions or jumping to conclusions without establishing facts and proper due diligence.

[46][49] However, many post-medieval era authors explicitly credit their inspirations to texts such as "Bidpai" and "Pilpay, the Indian sage" that are known to be based on the Panchatantra.

[57] The French fabulist Jean de La Fontaine acknowledged his indebtedness to the work in the introduction to his Second Fables: The Panchatantra is the origin also of several stories in Arabian Nights, Sindbad, and of many Western nursery rhymes and ballads.

[29] The Panchatantra shares many stories in common with the Buddhist Jataka tales, purportedly told by the historical Buddha before his death around 400 BCE.

[...] It is quite uncertain whether the author of [the Panchatantra] borrowed his stories from the Jātakas or the Mahābhārata, or whether he was tapping into a common treasury of tales, both oral and literary, of ancient India.

[61] In the early 20th century, W. Norman Brown found that many folk tales in India appeared to be borrowed from literary sources and not vice versa.

]According to Olivelle, "Indeed, the current scholarly debate regarding the intent and purpose of the 'Pañcatantra' — whether it supports unscrupulous Machiavellian politics or demands ethical conduct from those holding high office — underscores the rich ambiguity of the text".

"[66] The Panchatantra, states Patrick Olivelle, tells wonderfully a collection of delightful stories with pithy proverbs, ageless and practical wisdom; one of its appeal and success is that it is a complex book that "does not reduce the complexities of human life, government policy, political strategies, and ethical dilemmas into simple solutions; it can and does speak to different readers at different levels.

It is the 8th-century Kalila wa Demna text, states Riedel, that has been the most influential of the known Arabic versions, not only in the Middle East, but also through its translations into Greek, Hebrew and Old Spanish.

Ibn al-Muqaffa' inserted other additions and interpretations into his 750CE "re-telling" (see Francois de Blois' Burzōy's voyage to India and the origin of the book Kalīlah wa Dimnah).

[82] After the Arab invasion of Persia (Iran), Ibn al-Muqaffa's version (two languages removed from the pre-Islamic Sanskrit original) emerged as the pivotal surviving text that enriched world literature.

"[79] Some scholars believe that Ibn al-Muqaffa's translation of the second section, illustrating the Sanskrit principle of Mitra Laabha (Gaining Friends), became the unifying basis for the Brethren of Purity (Ikwhan al-Safa) — the anonymous 9th-century CE encyclopedists whose prodigious literary effort, Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Sincerity, codified Indian, Persian and Greek knowledge.

A suggestion made by Goldziher, and later written on by Philip K. Hitti in his History of the Arabs, proposes that "The appellation is presumably taken from the story of the ringdove in Kalilah wa-Dimnah in which it is related that a group of animals by acting as faithful friends (ikhwan al-safa) to one another escaped the snares of the hunter."

This story is mentioned as an exemplum when the Brethren speak of mutual aid in one risaala (treatise), a crucial part of their system of ethics.

From Arabic it was re-translated into Syriac in the 10th or 11th century, into Greek (as Stephanites and Ichnelates) in 1080 by the Jewish Byzantine doctor Simeon Seth,[85] into 'modern' Persian by Abu'l-Ma'ali Nasrallah Munshi in 1121, and in 1252 into Spanish (old Castilian, Calila e Dimna).

[90] Recently Ibn al-Muqaffa's historical milieu itself, when composing his masterpiece in Baghdad during the bloody Abbasid overthrow of the Umayyad dynasty, has become the subject (and rather confusingly, also the title) of a gritty Shakespearean drama by the multicultural Kuwaiti playwright Sulayman Al-Bassam.

[91] Ibn al-Muqqafa's biographical background serves as an illustrative metaphor for today's escalating bloodthirstiness in Iraq — once again a historical vortex for clashing civilisations on a multiplicity of levels, including the obvious tribal, religious and political parallels.

Anyone with any claim to a literary education knew that the Fables of Bidpai or the Tales of Kalila and Dimna — these being the most commonly used titles with us — was a great Eastern classic.

It is not quite so strange, however, when one recalls that the Arabs had much preferred the poetic art and were at first suspicious of and untrained to appreciate, let alone imitate, current higher forms of prose literature in the lands they occupied.

Its philosophical heroes through the initial interconnected episodes illustrating The Loss of Friends, the first Hindu principle of polity are the two jackals, Kalilah and Dimnah.