Binary mass function

In astronomy, the binary mass function or simply mass function is a function that constrains the mass of the unseen component (typically a star or exoplanet) in a single-lined spectroscopic binary star or in a planetary system.

It can be calculated from observable quantities only, namely the orbital period of the binary system, and the peak radial velocity of the observed star.

The binary mass function follows from Kepler's third law when the radial velocity of one binary component is known.

[1] Kepler's third law describes the motion of two bodies orbiting a common center of mass.

For a given orbital separation, a higher total system mass implies higher orbital velocities.

On the other hand, for a given system mass, a longer orbital period implies a larger separation and lower orbital velocities.

Because the orbital period and orbital velocities in the binary system are related to the masses of the binary components, measuring these parameters provides some information about the masses of one or both components.

Unlike true orbital velocity, radial velocity can be determined from Doppler spectroscopy of spectral lines in the light of a star,[3] or from variations in the arrival times of pulses from a radio pulsar.

In this case, a lower limit on the mass of the other, unseen component can be determined.

[1] The true mass and true orbital velocity cannot be determined from the radial velocity because the orbital inclination is generally unknown.

(The inclination is the orientation of the orbit from the point of view of the observer, and relates true and radial velocity.

[5][6] For example, if the measured radial velocity is low, this can mean that the true orbital velocity is low (implying low mass objects) and the inclination high (the orbit is seen edge-on), or that the true velocity is high (implying high mass objects) but the inclination low (the orbit is seen face-on).

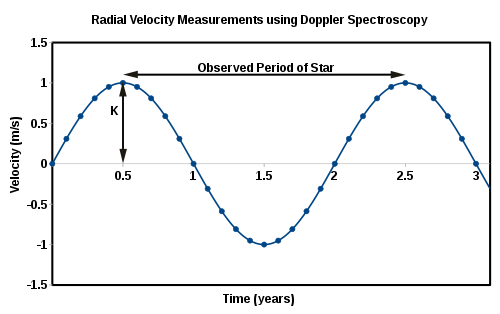

is the semi-amplitude of the radial velocity curve, as shown in the figure.

is found from the periodicity in the radial velocity curve.

These are the two observable quantities needed to calculate the binary mass function.

the distances of the objects to the center of mass.

is the semi-major axis (orbital separation) of the binary system.

of the observed object 1, a minimum mass

The inclination is typically not known, but to some extent it can be determined from observed eclipses,[2] be constrained from the non-observation of eclipses,[8][9] or be modelled using ellipsoidal variations (the non-spherical shape of a star in binary system leads to variations in brightness over the course of an orbit that depend on the system's inclination).

(for example, when the unseen object is an exoplanet[8]), the mass function simplifies to

(for example, when the unseen object is a high-mass black hole), the mass function becomes[2]

If the accretor in an X-ray binary has a minimum mass that significantly exceeds the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit (the maximum possible mass for a neutron star), it is expected to be a black hole.

This is the case in Cygnus X-1, for example, where the radial velocity of the companion star has been measured.

[13][14] An exoplanet causes its host star to move in a small orbit around the center of mass of the star-planet system.

This 'wobble' can be observed if the radial velocity of the star is sufficiently high.

This is the radial velocity method of detecting exoplanets.

[5][3] Using the mass function and the radial velocity of the host star, the minimum mass of an exoplanet can be determined.

[15][16]: 9 [12][17] Applying this method on Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the solar system, led to the discovery of Proxima Centauri b, a terrestrial planet with a minimum mass of 1.27 ME.

The radial velocity variations of the pulsar follow from the varying intervals between the arrival times of the pulses.

[4] The first exoplanets were discovered this way in 1992 around the millisecond pulsar PSR 1257+12.