Biomagnification

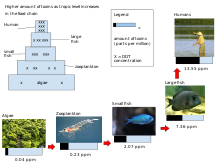

Biomagnification, also known as bioamplification or biological magnification, is the increase in concentration of a substance, e.g a pesticide, in the tissues of organisms at successively higher levels in a food chain.

[1] This increase can occur as a result of: Biological magnification often refers to the process whereby substances such as pesticides or heavy metals work their way into lakes, rivers and the ocean, and then move up the food chain in progressively greater concentrations as they are incorporated into the diet of aquatic organisms such as zooplankton, which in turn are eaten perhaps by fish, which then may be eaten by bigger fish, large birds, animals, or humans.

Biodilution is also a process that occurs to all trophic levels in an aquatic environment; it is the opposite of biomagnification, thus when a pollutant gets smaller in concentration as it progresses up a food web.

This process explains why predatory fish such as swordfish and sharks or birds like osprey and eagles have higher concentrations of mercury in their tissue than could be accounted for by direct exposure alone.

[8] In a review, a large number of studies, Suedel et al.[9] concluded that although biomagnification is probably more limited in occurrence than previously thought, there is good evidence that DDT, DDE, PCBs, toxaphene, and the organic forms of mercury and arsenic do biomagnify in nature.

The success of top predatory-bird recovery (bald eagles, peregrine falcons) in North America following the ban on DDT use in agriculture is testament to the importance of recognizing and responding to biomagnification.