Birkhoff's representation theorem

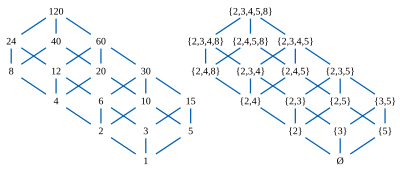

The union and intersection operations, in a family of sets that is closed under these operations, automatically form a distributive lattice, and Birkhoff's representation theorem states that every finite distributive lattice can be formed in this way.

[1] The theorem can be interpreted as providing a one-to-one correspondence between distributive lattices and partial orders, between quasi-ordinal knowledge spaces and preorders, or between finite topological spaces and preorders.

For instance, the Boolean lattice defined from the family of all subsets of a finite set has this property.

Birkhoff's theorem states that in fact all finite distributive lattices can be obtained this way, and later generalizations of Birkhoff's theorem state a similar thing for infinite distributive lattices.

From any lower set L, one can recover the associated divisor by computing the least common multiple of the prime powers in L. Thus, the partial order on the five prime powers 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 carries enough information to recover the entire original 16-element divisibility lattice.

Birkhoff's theorem states that this relation between the operations ∧ and ∨ of the lattice of divisors and the operations ∩ and ∪ of the associated sets of prime powers is not coincidental, and not dependent on the specific properties of prime numbers and divisibility: the elements of any finite distributive lattice may be associated with lower sets of a partial order in the same way.

Birkhoff's theorem states that any finite distributive lattice can be constructed in this way.

That is, there is a one-to-one order-preserving correspondence between elements of L and lower sets of the partial order.

Birkhoff's theorem, as stated above, is a correspondence between individual partial orders and distributive lattices.

[2] For, if ƒ is such a function, ƒ−1(0) forms a lower set, and conversely if L is a lower set one may define an order-preserving function ƒL that maps L to 0 and that maps the remaining elements of P to 1.

[3] Hilary Priestley showed that Stone's representation theorem could be interpreted as an extension of the idea of representing lattice elements by lower sets of a partial order, using Nachbin's idea of ordered topological spaces.

Stone spaces with an additional partial order linked with the topology via Priestley separation axiom can also be used to represent bounded distributive lattices.

Birkhoff's representation theorem may also be generalized to finite structures other than distributive lattices.

Finite median algebras and median graphs have a dual structure as the set of solutions of a 2-satisfiability instance; Barthélemy & Constantin (1993) formulate this structure equivalently as the family of initial stable sets in a mixed graph.

Equivalently, for a distributive lattice, the implication graph of the 2-satisfiability instance can be partitioned into two connected components, one on the positive variables of the instance and the other on the negative variables; the transitive closure of the positive component is the underlying partial order of the distributive lattice.

Another result analogous to Birkhoff's representation theorem, but applying to a broader class of lattices, is the theorem of Edelman (1980) that any finite join-distributive lattice may be represented as an antimatroid, a family of sets closed under unions but in which closure under intersections has been replaced by the property that each nonempty set has a removable element.