Oil shale

Oil shale is an organic-rich fine-grained sedimentary rock containing kerogen (a solid mixture of organic chemical compounds) from which liquid hydrocarbons can be produced.

[9] Oil shale can be burned directly in furnaces as a low-grade fuel for power generation and district heating or used as a raw material in chemical and construction-materials processing.

[1] Heating oil shale to a sufficiently high temperature causes the chemical process of pyrolysis to yield a vapor.

[10] Oil-shale mining and processing raise a number of environmental concerns, such as land use, waste disposal, water use, waste-water management, greenhouse-gas emissions and air pollution.

[14][15] According to the petrologist Adrian C. Hutton of the University of Wollongong, oil shales are not "geological nor geochemically distinctive rock but rather 'economic' term".

[1][13] Inorganic matrix can contain quartz, feldspar, clay (mainly illite and chlorite), carbonate (calcite and dolomite), pyrite and some other minerals.

[22] Another classification, known as the van Krevelen diagram, assigns kerogen types, depending on the hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen content of oil shales' original organic matter.

[15] The most commonly used classification of oil shales, developed between 1987 and 1991 by Adrian C. Hutton, adapts petrographic terms from coal terminology.

This classification designates oil shales as terrestrial, lacustrine (lake-bottom-deposited), or marine (ocean bottom-deposited), based on the environment of the initial biomass deposit.

[6] For comparison, at the same time the world's proven oil reserves are estimated to be 1.6976 trillion barrels (269.90 billion cubic metres).

[34] Britons of the Iron Age used tractable oil shales to fashion cists for burial,[35] or just polish it to create ornaments.

[36] In the 10th century, the Arab physician Masawaih al-Mardini (Mesue the Younger) described a method of extraction of oil from "some kind of bituminous shale".

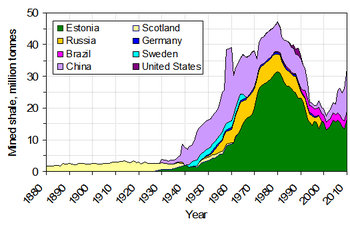

[34][38][39] Modern industrial mining of oil shale began in 1837 in Autun, France, followed by exploitation in Scotland, Germany, and several other countries.

[45] The Scottish oil-shale industry expanded immediately before World War I partly because of limited access to conventional petroleum resources and the mass production of automobiles and trucks, which accompanied an increase in gasoline consumption; but mostly because the British Admiralty required a reliable fuel source for their fleet as war in Europe loomed.

Although the Estonian and Chinese oil-shale industries continued to grow after World War II, most other countries abandoned their projects because of high processing costs and the availability of cheaper petroleum.

[48] In 1986, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985, which among other things abolished the United States' Synthetic Liquid Fuels Program.

Several additional countries started assessing their reserves or had built experimental production plants, while others had phased out their oil shale industry.

[56] Israel, Romania and Russia have in the past run power plants fired by oil shale but have shut them down or switched to other fuel sources such as natural gas.

[60] In comparison, production of the conventional oil and natural gas liquids in 2008 amounted 3.95 billion tonnes or 82.1 million barrels per day (13.1×10^6 m3/d).

Most conversion technologies involve heating shale in the absence of oxygen to a temperature at which kerogen decomposes (pyrolyses) into gas, condensable oil, and a solid residue.

Such technologies can potentially extract more oil from a given area of land than ex-situ processes, since they can access the material at greater depths than surface mines can.

[1][68] Some oil shales yield sulfur, ammonia, alumina, soda ash, uranium, and nahcolite as shale-oil extraction byproducts.

The higher concentrations of these materials means that the oil must undergo considerable upgrading (hydrotreating) before serving as oil-refinery feedstock.

[27] According to the New Policies Scenario introduced in its World Energy Outlook 2010, a price of $50 per tonne of emitted CO2 adds additional $7.50 cost per barrel of shale oil.

A 1972 publication in the journal Pétrole Informations (ISSN 0755-561X) compared shale-based oil production unfavorably with coal liquefaction.

In addition, the atmospheric emissions from oil shale processing and combustion include carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas.

Environmentalists oppose production and usage of oil shale, as it creates even more greenhouse gases than conventional fossil fuels.

[81] Experimental in situ conversion processes and carbon capture and storage technologies may reduce some of these concerns in the future, but at the same time they may cause other problems, including groundwater pollution.

[62][85][86][87] A 2008 programmatic environmental impact statement issued by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management stated that surface mining and retort operations produce 2 to 10 U.S. gallons (7.6 to 37.9 L; 1.7 to 8.3 imp gal) of waste water per 1 short ton (0.91 t) of processed oil shale.

In one result, Queensland Energy Resources put the proposed Stuart Oil Shale Project in Australia on hold in 2004.