Black-body radiation

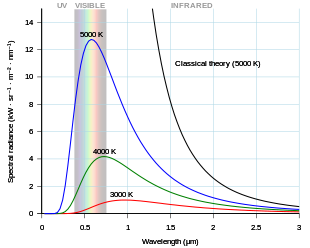

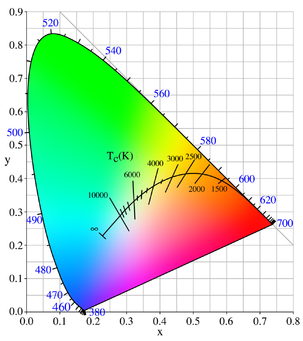

It has a specific, continuous spectrum of wavelengths, inversely related to intensity, that depend only on the body's temperature, which is assumed, for the sake of calculations and theory, to be uniform and constant.

Of particular importance, although planets and stars (including the Earth and Sun) are neither in thermal equilibrium with their surroundings nor perfect black bodies, blackbody radiation is still a good first approximation for the energy they emit.

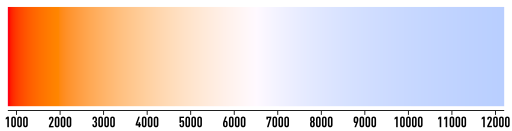

[9][10][11] As the temperature increases past about 500 degrees Celsius, black bodies start to emit significant amounts of visible light.

[15] A closed box with walls of graphite at a constant temperature with a small hole on one side produces a good approximation to ideal blackbody radiation emanating from the opening.

[15] In equilibrium, for each frequency, the intensity of radiation which is emitted and reflected from a body relative to other frequencies (that is, the net amount of radiation leaving its surface, called the spectral radiance) is determined solely by the equilibrium temperature and does not depend upon the shape, material or structure of the body.

No matter how the oven is constructed, or of what material, as long as it is built so that almost all light entering is absorbed by its walls, it will contain a good approximation to blackbody radiation.

Real objects never behave as full-ideal black bodies, and instead the emitted radiation at a given frequency is a fraction of what the ideal emission would be.

If this prediction is correct, black holes will very gradually shrink and evaporate over time as they lose mass by the emission of photons and other particles.

For example, a black body at room temperature (300 K) with one square meter of surface area will emit a photon in the visible range (390–750 nm) at an average rate of one photon every 41 seconds, meaning that, for most practical purposes, such a black body does not emit in the visible range.

[24] The study of the laws of black bodies and the failure of classical physics to describe them helped establish the foundations of quantum mechanics.

According to the Classical Theory of Radiation, if each Fourier mode of the equilibrium radiation (in an otherwise empty cavity with perfectly reflective walls) is considered as a degree of freedom capable of exchanging energy, then, according to the equipartition theorem of classical physics, there would be an equal amount of energy in each mode.

Instead, in the quantum treatment of this problem, the numbers of the energy modes are quantized, attenuating the spectrum at high frequency in agreement with experimental observation and resolving the catastrophe.

[27] The Stefan–Boltzmann law also says that the total radiant heat energy emitted from a surface is proportional to the fourth power of its absolute temperature.

where For a black body surface, the spectral radiance density (defined per unit of area normal to the propagation) is independent of the angle

Ambient air motion, causing forced convection, or evaporation reduces the relative importance of radiation as a thermal-loss mechanism.

Ignoring the atmosphere and greenhouse effect, the planet, since it is at a much lower temperature than the Sun, emits mostly in the infrared (IR) portion of the spectrum.

Estimates are often based on the solar constant (total insolation power density) rather than the temperature, size, and distance of the Sun.

Prior to this time, most matter in the universe was in the form of an ionized plasma in thermal, though not full thermodynamic, equilibrium with radiation.

[52] A black body at room temperature (23 °C (296 K; 73 °F)) radiates mostly in the infrared spectrum, which cannot be perceived by the human eye,[53] but can be sensed by some reptiles.

Tungsten filament lights have a continuous black body spectrum with a cooler colour temperature, around 2,700 K (2,430 °C; 4,400 °F), which also emits considerable energy in the infrared range.

[58] Stewart chose lamp-black surfaces as his reference because of various previous experimental findings, especially those of Pierre Prevost and of John Leslie.

Stewart's statement assumed a general principle: that there exists a body or surface that has the greatest possible absorbing and radiative power for every wavelength and equilibrium temperature.

He made his measurements in a room temperature environment, and quickly so as to catch his bodies in a condition near the thermal equilibrium in which they had been prepared.

In 1859, Gustav Robert Kirchhoff reported the coincidence of the wavelengths of spectrally resolved lines of absorption and emission of visible light.

(In contrast with Balfour Stewart's, Kirchhoff's definition of his absorption ratio did not refer in particular to a lamp-black surface as the source of the incident radiation.)

[61][62] But more importantly, it relied on a new theoretical postulate of "perfectly black bodies," which is the reason why one speaks of Kirchhoff's law.

Planck's black bodies radiated and absorbed only by the material in their interiors; their interfaces with contiguous media were only mathematical surfaces, capable neither of absorption nor emission, but only of reflecting and transmitting with refraction.

His proof noted that the dimensionless wavelength-specific absorptivity a(λ, T, BB) of a perfectly black body is by definition exactly 1.

It vanishes at low temperatures for visible wavelengths, which does not depend on the nature i of the arbitrary non-ideal body (Geometrical factors, taken into detailed account by Kirchhoff, have been ignored in the foregoing).

Thus Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation can be stated: For any material at all, radiating and absorbing in thermodynamic equilibrium at any given temperature T, for every wavelength λ, the ratio of emissive power to absorptivity has one universal value, which is characteristic of a perfect black body, and is an emissive power which we here represent by Bλ (λ, T).