Black Codes (United States)

[4][5][6]) Black Codes were part of a larger pattern of Democrats trying to maintain political dominance and suppress the freedmen, newly emancipated African-Americans.

The defining feature of the Black Codes was broad vagrancy law, which allowed local authorities to arrest freed people for minor infractions and commit them to involuntary labor.

[11] In many Southern states, particularly after Nat Turner's insurrection of 1831, they were denied the rights of citizens to assemble in groups, bear arms, learn to read and write, exercise free speech, or testify against white people in Court.

[26] The 1848 Constitution of Illinois contributed to the state legislature passing one of the harshest Black Code systems in the nation until the Civil War.

[27] However, while slavery was illegal in Illinois, landowners in the southern parts of the state would legally bring in slaves from adjacent Kentucky, and force them to do agricultural work for no wages.

Wendell Phillips said that Lincoln's proclamation had "free[d] the slave, but ignore[d] the Negro", calling the Banks-Thomas year-long contracts tantamount to serfdom.

[44] In the view of one contemporary economist, freed people exhibited this "noncapitalist behavior" because the condition of being owned had "shielded the slaves from the market economy" and they were therefore unable to perform "careful calculation of economic opportunities".

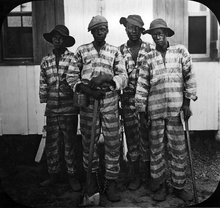

[57] This created a system that established incentives to arrest black men, as convicts were supplied to local governments and planters as free workers.

Another important part of the Codes were the annual labor contracts, which Black people had to keep and present to authorities to avoid vagrancy charges.

[58] Some states explicitly curtailed Black people's right to bear arms, justifying these laws with claims of imminent insurrection.

The Black Codes, along with the appointment of prominent Confederates to Congress, signified that the South had been emboldened by Johnson and intended to maintain its old political order.

[66] After winning large majorities in the 1866 elections, the Republican Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts, placing the South under military rule.

[71] Because legal enforcement depended on so many different local codes, which underwent less scrutiny than statewide legislation, historians still lack a complete understanding of their full scope.

[72] It is clear, however, that even under military rule, local jurisdictions were able to continue a racist pattern of law enforcement, as long as it took place under a legal regime that was superficially race-neutral.

[79] A general system of legitimized anti-Black violence, as exemplified by the Ku Klux Klan, played a major part in enforcing the practical law of white supremacy.

In the case of blacks, however: "the duty of the sheriff of the proper county to hire out said freedman, free negro or mulatto, to any person who will, for the shortest period of service, pay said fine or forfeiture and all costs.

[85] Other laws prevented blacks from buying liquor and carrying weapons; punishment often involved "hiring out" the culprit's labor for no pay.

[87] The next state to pass Black Codes was South Carolina, which had on November 13 ratified the Thirteenth Amendment—with a qualification that Congress did not have the authority to regulate the legal status of freedmen.

Newly elected governor James Lawrence Orr said that blacks must be "restrained from theft, idleness, vagrancy and crime, and taught the absolute necessity of strictly complying with their contracts for labor".

[89] The South Carolina law created separate courts for Black people, and authorized capital punishment for crimes including theft of cotton.

[96]General Daniel Sickles, head of the Freedmen's Bureau in South Carolina, followed Howard's lead and declared the laws invalid in December 1865.

[102] Thomas W. Conway, the Freedmen's Bureau commissioner for Louisiana, testified in 1866:[31] Some of the leading officers of the state down there—men who do much to form and control the opinions of the masses—instead of doing as they promised, and quietly submitting to the authority of the government, engaged in issuing slave codes and in promulgating them to their subordinates, ordering them to carry them into execution, and this to the knowledge of state officials of a higher character, the governor and others. ...

The most odious features of slavery were preserved in them.Conway describes surveying the Louisiana jails and finding large numbers of Black men who had been secretly incarcerated.

Salmon Chase, as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, eventually overruled the Maryland apprentice laws on the grounds of their violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

[113] "Negroes" were not allowed to vote, hold office, sit on juries, serve in local militia, carry guns on plantations, homestead, or attend public schools.

[114] In 1865, Tennessee freedpeople had no legal status whatsoever, and local jurisdictions often filled the void with extremely harsh Black Codes.

[136] The Bureau attempted to cancel a racially discriminatory apprenticeship law (which stipulated that only White children learn to read) but found itself thwarted by local authorities.

[70] After creating the Civil Rights Section in 1939, the Federal Department of Justice launched a wave of successful Thirteenth Amendment prosecutions against involuntary servitude in the South.

[148] One theory suggests that particularly restrictive laws emerge in larger countries (compare Jamaica with the United States) where the ruling group does not occupy land at a high enough density to prevent the freed people from gaining their own.

[152] Given the pattern of economic continuity, writes economist Pieter Emmer, "the words emancipation and abolition must be regarded with the utmost suspicion.