Black Hawk War

The war erupted after Black Hawk and a group of Sauks, Meskwakis (Fox), and Kickapoos, known as the "British Band", crossed the Mississippi River, to the U.S. state of Illinois, from Iowa Indian Territory in April 1832.

The war gave impetus to the U.S. policy of Indian removal, in which Native American tribes were pressured to sell their lands and move west of the Mississippi River to reside.

[7] Historian Patrick Jung concluded that the Sauk and Meskwaki chiefs intended to cede a little land, but that the Americans included more territory in the treaty's language than the Natives realized.

[14] Keokuk regarded the 1804 treaty as a fraud, but after having seen the size of American cities on the east coast in 1824, he did not think the Sauks could successfully oppose the United States.

General Edmund P. Gaines, commander of the Western Department of the United States Army, assembled troops with the hope of intimidating Black Hawk into leaving.

The army had no cavalry to pursue the Sauks should they flee further into Illinois on horseback, and so on June 5 Gaines requested that the state militia provide a mounted battalion.

The island had been named for a farmer and trader who operated a ferry, as well as sold liquor to the natives, which had previously prompted a raid by Black Hawk to destroy the whiskey.

[29] This time, underbrush had grown to impede the militiamen from landing, so the next day the militia tried to assault Saukenuk itself, only to find that Black Hawk and his followers had abandoned the village and recrossed the Mississippi.

[34] According to Neapope's erroneous report, Wabokieshiek ("White Cloud"), a shaman known to Americans as the "Winnebago Prophet", had claimed that other tribes were ready to support Black Hawk.

[37] Although some Americans would later characterize Wabokieshiek as a primary instigator of the Black Hawk War, the Winnebago Prophet, according to historian John Hall, "actually discouraged his followers from resorting to armed conflict with the whites".

[53] American officials discouraged the Menominees from seeking revenge, but the western bands of the tribe formed a coalition with the Dakotas to strike at the Sauks and Meskwakis.

[60] Reynolds, who was eager for a war to drive the Indians out of the state, responded as Atkinson had hoped: he called for militia volunteers to assemble at Beardstown by April 22 to begin a thirty-day enlistment.

[75] General Samuel Whiteside's militia brigade had been mustered into federal service at Rock Island under General Atkinson in late April, and divided into four regiments (commanded by Colonels John DeWitt, Jacob Fry, John Thomas, and Samuel M. Thompson), and a scout or spy battalion commanded by James D. Henry,[76] with judge William Thomas as their quartermaster.

Atkinson had allowed Reynolds, Whiteside, and the militiamen to leave up the Rock River on April 27, while he brought up the rear with the regular soldiers, directing his least trained and disciplined men—to "move upon the Indians should they be within striking distance without waiting for my arrival".

Accepting an offer from the Rock River Ho-Chunks, the band traveled further upriver to Lake Koshkonong in the Michigan Territory and camped in an isolated place known as the "Island".

[90] Not all Native Americans in the region supported this turn of events; most notably, Potawatomi chief Shabonna rode throughout the settlements, warning settlers of the impending attacks.

On May 21, about fifty Potawatomis and three Sauks from the British Band attacked Davis's settlement, killing, scalping, and mutilating fifteen men, women, and children.

Henry Dodge, a Michigan territorial militia colonel who would prove to be one of the best commanders in the war,[108] fielded a battalion of mounted volunteers that numbered 250 men at its strongest.

[120] Back on June 6, when a civilian miner was killed by raiders near the village of Blue Mounds in the Michigan Territory, residents began to fear that the Rock River Ho-Chunks were joining the war.

[130] On July 29, Scott began a hurried journey west, ahead of his troops, eager to take command of what was certain to be the war's final campaign, but he would be too late to see any combat.

Tribal leaders knew that some of their warriors had aided the British Band, and so they hoped that a highly visible show of support for the Americans would dissuade U.S. officials from punishing the tribes after the conflict was over.

[135] In mid-July, Colonel Dodge learned from métis trader Pierre Paquette that the British Band was camped near the Rock River rapids, at present Hustisford, Wisconsin.

[142] Black Hawk had managed to hold off a much larger force while allowing most of his people to escape, a difficult military operation that impressed some U.S. Army officers when they learned of it.

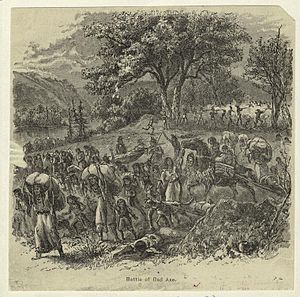

[153] The next morning, on August 2, Black Hawk was heading north when he learned that the American army had closed in on the members of the British Band who were trying to cross the Mississippi.

[157] The battle was another lopsided victory for the Americans, who lost just 14 men, including one Menominee who died by friendly fire and was buried with honors alongside the US soldiers.

[160] Indian agent Samuel C. Stambaugh, who accompanied them, urged the Menominees not to take any scalps, but Chief Grizzly Bear insisted that such a prohibition could not be enforced.

[162] The Dakotas, who had volunteered 150 warriors to fight against the Sauks and Meskwakis, also arrived too late to participate in the Battle of Bad Axe, but they pursued the members of the British Band who made it across the Mississippi into Iowa.

[174] Even in prison they were treated as celebrities: they posed for portraits by artists such as Charles Bird King and John Wesley Jarvis, and a dinner was held in their honor before they left.

[178] According to historian Kerry Trask, Black Hawk and his fellow prisoners were treated like celebrities because the Indians served as a living embodiment of the noble savage myth that had become popular in the eastern United States.

[188] Following the September 1832 treaty with the Ho-Chunks, Scott and Reynolds conducted another with the Sauks and Meskwakis, with Keokuk and Wapello serving as the primary representatives of their tribes.