Picea glauca

Picea glauca is native from central Alaska all through the east, across western and southern/central Canada to the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland, Quebec, Ontario and south to Montana, North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Upstate New York and Vermont, along with the mountainous and immediate coastal portions of New Hampshire and Maine, where temperatures are just barely cool and moist enough to support it.

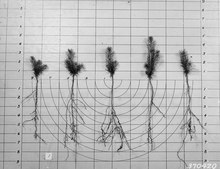

[24] In the nursery, or naturally in the forest, white spruce usually develops several long 'running' roots just below the ground surface.

[25] The structure of the tracheids in the long lateral roots of white spruce varies with soil nitrogen availability.

White spruce 6 to 10 m (20 to 33 ft) high on the shore of Urquhart Lake, Northwest Territories, were found to be more than 300 years old.

Its northern distribution roughly correlates to the location of the tree line, which includes an isothermic value of 10 °C (50 °F) for mean temperature in July, as well as the position of the Arctic front; cumulative summer degree days, mean net radiation, and the amount of light intensities also figure.

[57] The range of white spruce extends westwards from Newfoundland and Labrador, and along the northern limit of trees to Hudson Bay, Northwest Territories, Yukon, and into northwestern Alaska.

Other climatic factors that have been suggested as affecting the northern limit of white spruce include: cumulative summer degree days, position of the Arctic front in July, mean net radiation especially during the growing season, and low light intensities.

[71][72][73] In Scotland, at Corrour, Inverness-shire, Sir John Stirling Maxwell in 1907 began using white spruce in his pioneering plantations at high elevations on deep peat.

However, plantations in Britain have generally been unsatisfactory,[74] mainly because of damage by spring frosts after mild weather had induced flushing earlier in the season.

[76] In the far north, the total depth of the moss and underlying humus is normally between 25 and 46 cm (10 and 18 in), although it tends to be shallower when hardwoods are present in the stand.

Soil properties such as fertility, temperature, and structural stability are partial determinants of the ability of white spruce to grow in the extreme northern latitudes.

[77] The seeds are eaten by small mammals like the red squirrel and birds such as chickadee, nuthatch, and pine siskin.

[9] White spruce occurs on a wide variety of soils, including soils of glacial, lacustrine, marine, and alluvial origins; overlying basic dolomites, limestones and acidic Precambrian and Devonian granites and gneisses; and Silurian sedimentary schists, shales, slates, and conglomerates.

[78] The wide range of textures accommodated includes clays, even those that are massive when wet and columnar when dry, sand flats, and coarse soils.

[8] Podzolized, brunisolic, luvisolic, gleysolic, and regosolic (immature) soils are typical of those supporting white spruce throughout the range of the species.

[91] On dry, deep, outwash deposits in northern Ontario, both white spruce and aspen grow slowly.

[94] Minimum soil-fertility standards recommended for white spruce sufficient to produce 126 to 157 m3/ha of wood at 40 years are much higher than for pine species commonly planted in the Lake States (Wilde 1966):[95] 3.5% organic matter, 12.0 meq/100 g exchange capacity, 0.12% total N, 44.8 kg/ha available P, 145.7 kg/ha available K, 3.00 meq/100 g exchangeable Ca, and 0.70 meq/100 g exchangeable Mg. Forest floors under stands dominated by white spruce respond in ways that vary with site conditions, including the disturbance history of the site.

[96][97][98] Acidity of the mineral soil sampled at an average depth of 17 cm in 13 white spruce stands on abandoned farmland in Ontario increased by 1.2 pH units over a period of 46 years.

[102] High-lime ecotypes may exist,[103] and in Canada Forest Section B8 the presence of balsam poplar and white spruce on some of the moulded moraines and clays seems to be correlated with the considerable lime content of these materials,[41][104] while calcareous soils are favourable sites for northern outliers of white spruce.

Permafrost development in parts of Alaska, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories is facilitated by the insulative organic layer (Viereck 1970a, b, Gill 1975, Van Cleve and Yarie 1986).

[96][97][107][108] White spruce is extremely hardy to low temperatures, provided the plant is in a state of winter dormancy.

[109] Especially important in determining the response of white spruce to low temperatures is the physiological state of the various tissues, notably the degree of "hardening" or dormancy.

Floodplain deposits in the Northwest Territory, Canada, are important in relation to the development of productive forest types with a component of white spruce.

With increasing elevation, the shrubs give way successively to balsam poplar and white spruce forest.

In contrast, older floodplains, with predominantly brown wooded soils, typically carry white spruce–trembling aspen mixedwood forest.

Interrelationships among nutrient cycling, regeneration, and subsequent forest development on floodplains in interior Alaska were addressed by Van Cleve et al.,[116] who pointed out that the various stages in primary succession reflect physical, chemical, and biological controls of ecosystem structure and function.

Without application of substantial amounts of fertilizer, use would have to be made of early successional alder and its site-ameliorating additions of nitrogen.

Vascular plants are typically few, but shrubs and herbs that occur “with a degree of regularity” include: alder, willows, mountain cranberry, red-fruit bearberry, black crowberry, prickly rose, currant, buffaloberry, blueberry species, bunchberry, twinflower, tall lungwort, northern comandra, horsetail, bluejoint grass, sedge species, as well as ground-dwelling mosses and lichens.

[130] 'Conica' is a dwarf conifer with very slender leaves, like those normally found only on one-year-old seedlings, and very slow growth, typically only 2–10 cm (3⁄4–4 in) per year.

Older specimens commonly 'revert', developing normal adult foliage and starting to grow much faster; this 'reverted' growth must be pruned if the plant is to be kept dwarf.