Black Sea Germans

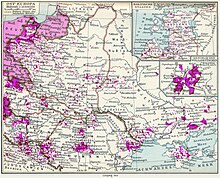

Germans began settling in southern Ukraine and the Crimean Peninsula in the late 18th century, but the bulk of immigration and settlement occurred during the Napoleonic period, from 1800 onward, with a concentration in the years 1803 to 1805.

The first German settlers arrived in 1787, first from West Prussia, then later from Western and Southwestern Germany and Alsace, France; as well as from the Warsaw area.

She granted them privileges such as the free exercise of their religion and language within their largely closed communities, also exempt from military service and taxation.

Other settlers from the Black Sea were Russian Mennonites and Hutterites, as well as Dobrujan Germans who had briefly lived in southeastern Romania.

North Dakota State University maintains an archive, the Germans From Russian Heritage Collection, concerning this immigrant group.

Due to the increasing scarcity of farmland in the Dakotas of the United States, many Black Sea Germans resettled in the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, where they left descendants.

[5] The Canadian Prairies, especially in the province of Alberta, received Black Sea Germans, especially between 1900 and 1913, when the expansion of the railway branches made them easily accessible to new settlers.

The next year, other Black Sea German families founded Colonia Monte La Plata, in Villarino Partido, same province.

Over the years, its inhabitants have migrated to other Argentine towns or cities; however, this cemetery is a testimony of the way in which both German communities have cooperated in the country, without losing their own identities.

Regarding the Russian Mennonites, in 1877, a small group had arrived in Argentina and settled near Olavarría, in Buenos Aires Province.

The German farmers were labelled kulaks (rich peasants) by the Communist regime, and those who did not voluntarily agree to give up their land to the Soviet farming collectives were expelled to Siberia and Central Asia.

Although the decree stated that old people would not have to leave, everyone was expelled, first to Stavropol, and then to Rostov in southeastern Ukraine, near the Crimea, but then all were sent on to camps and special settlements in Kazakhstan.

Between 25 September 1941 and 10 October 1941, approximately 105,000 ethnic Germans were exiled from this region and forcibly deported to Soviet-held areas far to the east beyond the Ural mountains.

In terms of total numbers deported to Siberia and Central Asia, between 15 August and 25 December 1941, the Soviet authorities expelled and exiled 856,000 German from Russia.

When the Soviet troops neared the Dnieper River in October 1943, the Chortitza Mennonite communities, totaling about 35,000 people, had to flee.

[6] This enclave of German settlement, established by the Russian imperial government, lies on the west bank of the Dnieper river in the Beryslav Raion district of Kherson Oblast, Ukraine, some 12 kilometers (or 7 Versts under the old Tsarist system of measurement) east-north-east (16.6 km by car,[7] and 16.4 km by approved footpaths [8]) of the town of Beryslav on the same side of the river.

Originally settled in 1782 by manumitted ethnic Swedish serfs from the Baltic island of Hiiumaa (Dagö) in present-day Estonia who were freed by Catherine the Great and invited to settle here, the district took its German name — Schwedengebiet translates as "Swedes' district" — from these earlier settlers, despite the fact that once the Germans began to arrive as official settlers during the Napoleonic period, they soon outnumbered their Swedish precursors.

In the period 1802–1806, after a generation alone, during which their numbers had been supplemented on occasion by Swedes captured in war and other, mostly temporary, sojourners from Danzig, the local Baltic Swedish community was faced with the arrival of German speakers.

This not only meant that they no longer had this area to themselves, but the Swedes had to share their original wooden church with some permanent incomers, ethnic German Lutherans.