Black market in wartime France

[3][4] The wage and hour concessions that emerged from the strikes have been blamed by some economists for the runaway inflation and subsequent stagflation that ensued, but more recent studies indicate that delay and reluctance to devalue the franc and abandon the gold standard were also factors, and possibly more important.

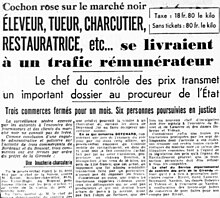

"[18] The Germans also required the French to finance the transportation of exports to Germany, and paid for their purchases with special currency pegged to an exchange rate that was artificially advantageous to them,[19] at 20 francs to one Reichsmark.

[30] Historian Kenneth Mouré, an authority on the period, wrote in 2022 that this was deliberate, "to punish French civilians", and set to match conditions in Germany's World War I Turnip Winter.

Another notable collaborator was Frédéric Martin, known by the pseudonym Rudy von Mérode, who with the help of the Devisenschutzkommando, seized gold from traffickers who used the black market on pain of arrest and managed to collect over four tons.

Through the black market, Szkolnikoff became one of the biggest real estate owners in France, with a hundred-odd exclusive buildings in Paris, luxury hotels in resort towns, a game preserve in Sologne and a chateau in Saône-et-Loire.

[75] This resentment was fueled by the major scandal known as the 'Meals on Wheels' affair, when from March to September 1941, a large number of buyers drove around in vans to buy food from farmers and were subsequently fined in the Allier department.

Between February and November 1941, François Darlan's Council of Ministers met to discuss the issue on ten occasions; the existence of the black market implied a failure of their supply policy.

This department gradually built up a nationwide administration of retired civil servants, customs agents and financial services staff, headed by Jean de Sailly, the Inspector of Finances.

[77][78][81] Price controls introduced by Vichy were based on three incorrect premises: The law of 7 December 1940 created supply inspectors who checked cards and tickets as well as the official declarations when a harvest was brought in or products were transported.

Two circulars from December 1941 gave them priority in food distribution, but since they never stopped developing, they created parallel direct supply channels, sometimes managed by employees using obfuscated accounting records.

Public opinion continued to decry the grand-scale black market in which some made their fortunes, but it condoned small daily compromises to survie, and therefore it no longer tolerated law enforcement targeting them.

"[43] On 13 December 1941, Emmanuel Célestin Suhard, Archbishop of Paris, emphasized the need to tolerate "modest illegal operations to obtain necessary food supplements, justified both by their small size and by the necessities of life.

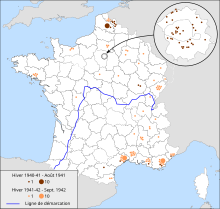

The proliferation of roadblocks in departements crossed by the line of demarcation[d] like the Cher, primarily resulted in arrests of city-dwellers on bicycles bringing home a few kilos of food they had bought at a farm.

Unable to bear the shame, a farmwife committed suicide after her conviction by the correctional court (tribunal correctionnel) of Charolles for selling butter without a ticket at a price slightly above the official rate.

For textiles in the metropolis of Lille-Roubaix-Tourcoing, tanning in the Millau region, and hosiery in Troyes and clockwork in Franche-Comté, inspectors found that between half and two thirds of all businesses were in violation of the law.

[126] Departments bisected by the line of demarcation, such as Indre-et-Loire, Cher or Saône-et-Loire, whose urban and industrial centres fell in the occupied zone and were separated from their natural hinterlands, also saw large-scale inter-zone trafficking on a regional and national level, usually based on bribes to German guards.

After the war, those suspected of profiteering continued to be called les BOF (butter, eggs, cheese)[129][128] In fact, retail commerce suffered less than any other economic sector under the occupation, with its share of national revenue jumping from 16% in 1938 to 24.5% in 1946, while the number of sellers increased.

The Paris police arrested people every day who were transporting meat, fruit, vegetables, tobacco or coffee in suitcases, on foot, bicycles or wheelbarrows, for example between the train stations and the addresses of their customers.

The Germans ceaselessly asked Max Bonnafous, minister of Agriculture and Supply, and René Bousquet, secretary general of the police, as well as Jean de Sailly, chief of the DGCE, for tougher enforcement.

"The convergence of diverse interests in opposition to controls – consumers, shopkeepers, producers, farmers, and even unions – was notable for its breadth and its impact," wrote historian Kenneth Mouré in 2022.

[148] On the other hand, the Resistance and Free France broadcasts on the BBC legitimized small transactions necessary to resupply, distinguishing them from the true black market and threatening traffickers with revenge after the coming Liberation.

The obstacles were numerous: the difficulty in precisely measuring illicit profits given the clandestine nature of the transactions, the frequent appeals, and, more fundamentally, the moral ambivalence of the defendants, since the black market had also been at the service of the Resistance.

[163][155][164][162] "State policies and enforcement practices alienated a remarkably wide range of producers, consumers and intermediaries whose interests often diverge, and ... insufficient food supply catalysed popular opposition to controls, wrote Moure in 2022.

[174] After the Liberation, the scale of continuing food shortages induced the Provisional Government of the French Republic to maintain the price control and organisational structures established by the Vichy regime, and retain their administrative personnel.

[179] On 30 June 1945, two decrees repealed Vichy legislation and also strengthened enforcement, making it a judicial not administrative matter and requiring the Contrôle économique to forward all cases to the public prosecutor.

[180][181] In 1946, a law sponsored by new Minister of Supply Yves Farge passed with a large majority; it introduced the death sentence for those who "increased the scarcity of food products", but this penalty was never imposed.

In a 2013 book review, historian Robert O. Paxton wrote: "The historiography of Vichy France since the 1970s has consisted largely of refuting the early postwar view that Marshal Pétain's regime was an alien import imposed for the moment by Nazi force.

According to the Canadian academic Yan Hamel, the book "proposed an apology for the black market and "débrouille" under the Occupation without any regard for the political and moral concerns that were at the heart of Resistance novels".

[202] It seeks to depict reality through the clandestine and nocturnal transport of meat in Paris[200] and shows the black market as a practice made essential by the rules imposed by the occupier, a necessary illegality in a way.

[195] The character played by Bourvil, an unemployed taxi driver, represents a significant social reality, i.e. the small black market intermediaries at the end of the supply chain, who survived through this activity.

(# of fines per 1000 consumers)