Blackfoot Confederacy

[2] Broader definitions include groups such as the Tsúùtínà (Sarcee) and A'aninin (Gros Ventre) who spoke quite different languages but allied with or joined the Blackfoot Confederacy.

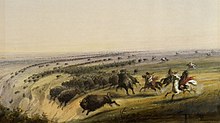

Historically, the member peoples of the Confederacy were nomadic bison hunters and trout fishermen, who ranged across large areas of the northern Great Plains of western North America, specifically the semi-arid shortgrass prairie ecological region.

The women worked the buffalo and other game skins for clothing, as well as to reinforce their dwellings; other elements were used to make warm fur robes, leggings, cords and other needed items.

[citation needed] Due to language and cultural patterns, anthropologists believe the Niitsitapi did not originate in the Great Plains of the Midwest North America, but migrated from the upper Northeastern part of the country.

[citation needed] They moved west and settled for a while north of the Great Lakes in present-day Canada, but had to compete for resources with existing tribes.

The Niitsitapi main source of food on the plains was the American bison (buffalo), the largest mammal in North America, standing about 6+1⁄2 feet (2.0 m) tall and weighing up to 2,000 pounds (910 kg).

[19] After driving the hostile Shoshone and Arapaho from the Northwestern Plains, the Niitsitapi began in 1800 a long phase of keen competition in the fur trade with their former Cree allies, which often escalated militarily.

Horse theft was at this stage not only a proof of courage, but often a desperate contribution to survival, for many ethnic groups competed for hunting in the grasslands.

Loosely allied with the Nehiyaw-Pwat, but politically independent, were neighboring tribes like the Ktunaxa, Secwepemc and in particular the arch enemy of the Blackfoot, the Crow, or Indian trading partners like the Nez Perce and Flathead.

By the late 1820s, [this prompted] the Niitsitapiksi, and in particular the Piikani, whose territory was rich in beaver, [to] temporarily put aside cultural prohibitions and environmental constraints to trap enormous numbers of these animals and, in turn, receive greater quantities of trade items.

[33] In 1833, German explorer Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied and Swiss painter Karl Bodmer spent months with the Niitsitapi to get a sense of their culture.

The Hudson's Bay Company did not require or help their employees get vaccinated; the English doctor Edward Jenner had developed a technique 41 years before but its use was not yet widespread.

One of their friendly bands, however, was attacked by mistake and nearly destroyed by the US Army in the Marias Massacre on 23 January 1870, undertaken as an action to suppress violence against settlers.

A friendly relationship with the North-West Mounted Police and learning of the brutality of the Marias Massacre discouraged the Blackfoot from engaging in wars against Canada and the United States.

[36] Despite his threats, Crowfoot later met those Lakota who had fled with Sitting Bull into Canada after defeating George Armstrong Custer and his battalion at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

The North-West Rebellion was made up mostly of Métis, Assiniboine (Nakota) and Plains Cree, who all fought against European encroachment and destruction of Bison herds.

Although he refused to fight, Crowfoot had sympathy for those with the rebellion, especially the Cree led by such notable chiefs as Poundmaker, Big Bear, Wandering Spirit and Fine-Day.

[38] When news of continued Blackfoot neutrality reached Ottawa, Lord Lansdowne, the governor general, expressed his thanks to Crowfoot again on behalf of the Queen back in London.

[clarification needed] Events were catalyzed by Owl Child, a young Piegan warrior who stole a herd of horses in 1867 from an American trader named Malcolm Clarke.

On 23 January 1870, a camp of Piegan Indians were spotted by army scouts and reported to the dispatched cavalry, but it was mistakenly identified as a hostile band.

Heavy Runner was shot and killed by army scout Joe Cobell, whose wife was part of the camp of the hostile Mountain Chief, further along the river, from whom he wanted to divert attention.

The greatest slaughter of Indians ever made by U.S. TroopsAs reports of the massacre gradually were learned in the east, members of the United States Congress and press were outraged.

They required Blackfoot children to go to boarding schools, where they were forbidden to speak their native language, practise customs, or wear traditional clothing.

The title of war chief could not be gained through election and needed to be earned by successfully performing various acts of bravery including touching a living enemy.

Girls were given a doll to play with, which also doubled as a learning tool because it was fashioned with typical tribal clothing and designs and also taught the young women how to care for a child.

[65] Similar to other Indigenous Peoples of the Great Plains, the Blackfoot developed a variety of different headdresses that incorporated elements of creatures important to them; these served different purposes and symbolized different associations.

It starts with a family of a man, wife, and two sons, who live off berries and other food they can gather, as they have no bows and arrows, or other tools (albeit a stone axe).

They are divided into the Piikani Nation (Aapátohsipikáni ("the companion up there") or simply Piikáni) in present-day Alberta, and the South Peigan or Piegan Blackfeet (Aamsskáápipikani) in Montana, United States.

Early scholars thought the A'aninin were related to the Arapaho Nation, who inhabited the Missouri Plains and moved west to Colorado and Wyoming.

Within the map is depicted a warrior's headdress and the words "Blackfeet Nation" and "Pikuni" (the name of the tribe in the Algonquian native tongue of the Blackfoot).