Trinity

[12][13] The doctrine of the Trinity was first formulated among the early Christians (mid-2nd century and later) and fathers of the Church as they attempted to understand the relationship between Jesus and God in their scriptural documents and prior traditions.

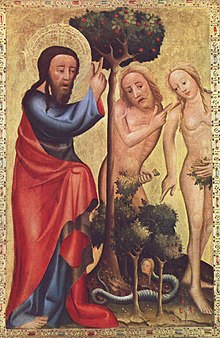

[...] "Then the LORD God said, 'Behold, the man has become like one of us in knowing good and evil [...]"A traditional Christian interpretation of these pronouns is that they refer to a plurality of persons within the Godhead.

[18] Another verse used to support the Deity of Christ is[19] "I saw in the night visions, and behold, with the clouds of heaven there came one like a son of man, and he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him.

[citation needed] People also see the Trinity when the Old Testament refers to God's word (Psalm 33:6), His Spirit (Isaiah 61:1), and Wisdom (Proverbs 9:1), as well as narratives such as the appearance of the three men to Abraham.

Eventually, the diverse references to God, Jesus, and the Spirit found in the New Testament were brought together to form the concept of the Trinity—one Godhead subsisting in three persons and one substance.

Verse 7 is known as the Johannine Comma, which most scholars agree to be a later addition by a later copyist or what is termed a textual gloss[31] and not part of the original text.

The Gospels depict Jesus as human through most of their narrative, but "[o]ne eventually discovers that he is a divine being manifest in flesh, and the point of the texts is in part to make his higher nature known in a kind of intellectual epiphany.

[50] However, in a 1973 Journal of Biblical Literature article, Philip B. Harner, Professor Emeritus of Religion at Heidelberg College, claimed that the traditional translation of John 1:1c ("and the Word was God") is incorrect.

[58] However, influential theologians such as Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas argued this statement was to be understood as Jesus speaking about his human nature.

To cite other examples of this, in Acts the Spirit alerts Peter to the arrival of visitors from Cornelius (10:19), directs the church in Antioch to send forth Barnabas and Saul (13:2–4), guides the Jerusalem council to a decision about Gentile converts (15:28), at one point forbids Paul to missionize in Asia (16:6), and at another point warns Paul (via prophetic oracles) of trouble ahead in Jerusalem (21:11).

[64] While the developed doctrine of the Trinity is not explicit in the books that constitute the New Testament, it was first formulated as early Christians attempted to understand the relationship between Jesus and God in their scriptural documents and prior traditions.

For example, he describes that the Son and Father are the same "being" (ousia) and yet are also distinct faces (prosopa), anticipating the three persons (hypostases) that come with Tertullian and later authors.

[75] At another point, Justin Martyr wrote that "we worship him [Jesus Christ] with reason, since we have learned that he is the Son of the living God himself, and believe him to be in second place and the prophetic Spirit in the third" (1 Apology 13, cf.

About the Christian Baptism, he wrote that "in the name of God, the Father and Lord of the universe, and of our Saviour Jesus Christ, and of the Holy Spirit, they then receive the washing with water", highlighting the liturgical use of a Trinitarian formula.

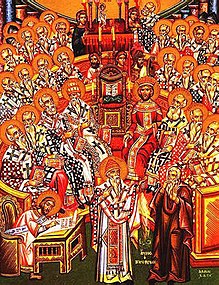

)[82][83] The concept of the Trinity can be seen as developing significantly during the first four centuries by the Church Fathers in reaction to theological interpretations known as Adoptionism, Sabellianism, and Arianism.

Magliola goes on to explain: Because such is the case (among other reasons), Karl Rahner rejects the "psychological" theories of Trinity which define the Father as Knower, for example, and the Son as the Known (i.e., Truth).

[120] The most prominent exponent of perichoresis was John of Damascus (d. 749) who employed the concept as a technical term to describe both the interpenetration of the divine and human natures of Christ and the relationship between the hypostases of the Trinity.

Let us rather, in a sense befitting the Godhead, perceive a transmission of will, like the reflexion of an object in a mirror, passing without note of time from Father to Son.

This concept was later taken by both Reformed and Catholic theology: in 1971 by Jürgen Moltmann's The Crucified God; in the 1972 "Preface to the Second Edition" of his 1969 German book Theologie der drei Tage (English translation: The Mystery of Easter) by Hans Urs von Balthasar, who took a cue from Revelation 13:8 (Vulgate: agni qui occisus est ab origine mundi, NIV: "the Lamb who was slain from the creation of the world") to explore the "God is love" idea as an "eternal super-kenosis".

[138] In the words of von Balthasar: "At this point, where the subject undergoing the 'hour' is the Son speaking with the Father, the controversial 'Theopaschist formula' has its proper place: 'One of the Trinity has suffered.'

Christians confess that the Trinity is fundamentally incomprehensible, and thus Christian confessions tend to maintain the doctrine as it is revealed in Scripture, but do not attempt to exhaustively analyse it or set forth its essence comprehensively, as Louis Berkhof describes in his Systematic Theology.The Trinity is a mystery, not merely in the Biblical sense that it is a truth, which is formerly hidden, but is now revealed; but in the sense that man cannot comprehend it and make it intelligible.

[172] Although social trinitarianism is a diverse theological movement, many of its advocates argue that each of the persons of the trinity are to be defined as three centers of consciousness with each having their own individual volitions.

[174][175] Nontrinitarianism (or antitrinitarianism) refers to Christian belief systems that reject the doctrine of the Trinity as found in the Nicene Creed as not having a scriptural origin.

Various nontrinitarian views, such as Adoptionism, Monarchianism, and Arianism existed prior to the formal definition of the Trinity doctrine in AD 325, 360, and 431, at the Councils of Nicaea, Constantinople, and Ephesus, respectively.

Similarly, Gabriel Reynolds, Sidney Griffith and Mun'im Sirry argue that this Quranic verse is to be understood as an intentional caricature and rhetorical statement to warn from the dangers of deifiying Jesus or Mary.

[188][189] The Trinity is most commonly seen in Christian art with the Spirit represented by a dove, as specified in the Gospel accounts of the Baptism of Christ; he is nearly always shown with wings outspread.

The usual depiction of the Father as an older man with a white beard may derive from the biblical Ancient of Days, which is often cited in defense of this sometimes controversial representation.

In early medieval art, the Father may be represented by a hand appearing from a cloud in a blessing gesture, for example in scenes of the Baptism of Christ.

In this style, the Father (sometimes seated on a throne) is shown supporting either a crucifix[192] or, later, a slumped crucified Son, similar to the Pietà (this type is distinguished in German as the Not Gottes),[193] in his outstretched arms, while the Dove hovers above or in between them.

By the end of the 15th century, larger representations, other than the Throne of Mercy, became effectively standardised, showing an older figure in plain robes for the Father, Christ with his torso partly bare to display the wounds of his Passion, and the dove above or around them.