Blombos Cave

The archaeological record from this cave site has been central in the ongoing debate on the cognitive and cultural origin of early humans and to the current understanding of when and where key behavioural innovations emerged among Homo sapiens in southern Africa during the Late Pleistocene.

100,000–70,000 years BP – are considered to represent greater ecological niche adaptation, a more diverse set of subsistence and procurements strategies, adoption of multi-step technology and manufacture of composite tools, stylistic elaboration, increased economic and social organisation and occurrence of symbolically mediated behaviour.

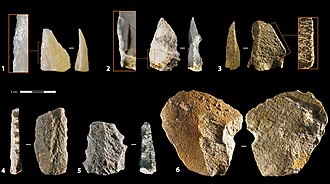

The most informative archaeological material from Blombos Cave includes engraved ochre,[9][10] engraved bone[11] ochre processing kits,[3] marine shell beads,[12][13][14] refined bone and stone tools[15][16][17][18][19] and a broad range of terrestrial and marine faunal remains, including shellfish, birds, tortoise and ostrich egg shell, and mammals of various sizes.

[20][21][22] These findings, together with subsequent re-analysis and excavation of other Middle Stone Age sites in southern Africa, have resulted in a paradigm shift with regard to the understanding of the timing and location of the development of modern human behaviour.

From the initial excavations conducted in the early 1990s, the Blombos Cave project has adopted and established new and innovative research agendas in the study of southern African prehistory.

The talus, which primarily consists of Middle Stone Age deposit, rock fall and unconsolidated sediments, is stabilized by an area of large, exposed blocks (14 m2).

Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) rich ground water seeps in from the cave roof and percolates through the interior sediments, resulting in an alkaline environment with good preservation conditions.

Intermixed with these sandy matrices are decomposed marine and terrestrial faunal remains (fish, shellfish, egg shell, and animal bones) and organic material.

101,000–70,000 years ago through a number of methods, including: thermoluminescence (TL),[1] optically stimulated luminescence (OSL),[2][3][4][30][31] uranium-thorium series (U/Th)[3] and electron spin resonance (ESR).

Critical remarks were in 2013[33] raised towards the luminescence-based Middle Stone Age chronology established by Jacobs et al. 2008[36] on methodological grounds related to errors in the manipulation of the luminescence data and estimation of uncertainties in the dose rates.

[21] Still Bay points may have served as tools with symbolic values attached to them – perhaps used as markers of identity – and integrated in social exchange networks,[42] similar to the ones observed ethnographically.

[43][44] Högberg and Larsson 2011 hypothesise that blanks and unfinished Still Bay points were purposely left behind in Hollow Rock Shelter, perhaps for use at a later stage or as an act of solidarity with other hunter-gatherer groups.

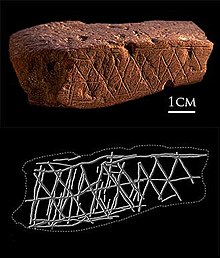

[45] According to the research published in the journal Nature, the find was "a prime indicator of modern cognition" in our species and an ochre crayon was used by early African Homo sapiens inscribed onto the stone.

[46][47][48][49] "The abrupt termination of all lines on the fragment edges indicates that the pattern originally extended over a larger surface," said archaeologist and lead author of the study Christopher Henshilwood.

[10] The surfaces of both pieces were intentionally modified by scraping and grinding, and the engraved pattern formed a distinct cross-hatched design in combination with parallel incised lines.

[59] The incised ochre pieces recovered from Blombos Cave and various other Middle Stone Age sites indicates that there was a spatial and temporal continuity in the production and use of conventional symbols in the region.

[45] Yet, recent studies also demonstrate that the mere occurrence of ochre in MSA contexts cannot be limited to a symbolic interpretation alone, but its use may also have served some functional role, e.g. as an ingredient in mastic, skin protection against sun or insects, as soft-hammers for delicate knapping, as a hide preservative or as medicine.

[3] Analysis shows that a liquefied pigment-rich mixture was produced and stored in the shells of two Haliotis midae (abalone), and that ochre, bone, charcoal, grindstones, and hammer-stones also formed a composite part of the toolkits.

Evidence for the complexity of the task includes procuring and combining raw materials from various sources (implying they had a mental template of the process they would follow), possibly using pyrotechnology to facilitate fat extraction from bone, using a probable recipe to produce the compound, and the use of shell containers for mixing and storage for later use.

[15][16][17][21] The awls that have been recovered are primarily made on long-bone shaft fragments, are shaped by scraping and may have been used to pierce through soft material – such as leather – or shell beads.

[13] Contextual information, morphometric, technological and use-wear analysis of the Blombos Cave beads, alongside experimental reproduction of wear patterns, show that the Nassarius kraussianus shells were strung, perhaps on cord or sinew and worn as a personal ornament.

Thus, the Blombos Cave beads may document one of the first examples where changes in complex social conventions directly can be traced through distinct variations in the production and use of symbolic material culture over time.

Further, syntactical language would have been essential for the sharing and transmission of the symbolic meaning of personal ornaments within and between groups and also over generations, as is also suggested for the engraved ochre pieces.

Besides Blombos Cave, there are a number of African and Middle East sites that all have yielded strong evidence for the early use of personal ornaments: Skul and Qafzeh, Israel,[71][72] Oued Djebbana, Algeria,[72] Grotte des Pigeons, Rhafas, Ifri n'Ammar and Contrebandiers, Morocco.

[20][21][22] The faunal record from Blombos Cave shows that Middle Stone Age people practiced a subsistence strategy that included a very broad range of animals.

[21][22] The amount of shellfish recovered from the various Middle Stone Age units show that people were regularly collecting them at the shore and bringing them back to the cave for consumption.

Fish are seldom reported from other southern African MSA sites, and by implication, it was thought that Middle Stone Age people were incapable of exploiting coastal resources efficiently.

[20] The huge variety of faunal and the shellfish remains recovered from all parts of the Blombos Cave Middle Stone Age sequence demonstrate that people during this period practiced a diverse set of subsistence and procurements strategies and were able to effectively hunt, trap and collect coastal, as well as terrestrial, resources.

[5][82][83][84][85][86] This is because aspects of MSA behaviours related to artefact production, subsistence, pigment use and migration patterns are increasingly being linked to periods of climatic, and by extension environmental change.

[5][36][78][82][86] The differing views regarding the role of past environmental change on Middle Stone Age people is also complicated by the wide range of climate proxies which can be interpreted at varying spatial and temporal resolutions.