National Recovery Administration

The goal of the administration was to eliminate "cut throat competition" by bringing industry, labor, and government together to create codes of "fair practices" and set prices.

In 1935, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously declared that the NRA law was unconstitutional, ruling that it infringed the separation of powers under the United States Constitution.

The long-term result was a surge in the growth and power of unions, which became a core of the New Deal Coalition that dominated national politics for the next three decades.

As part of the "First New Deal", the NRA was based on the premise that the Great Depression was caused by market instability and that government intervention was necessary to balance the interests of farmers, business and labor.

New Dealers who were part of the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt saw the close analogy with the earlier crisis handling the economics of World War I.

"[3][4] He further stated, "But if all employers in each trade now band themselves faithfully in these modern guilds—without exception—and agree to act together and at once, none will be hurt and millions of workers, so long deprived of the right to earn their bread in the sweat of their labor, can raise their heads again.

"[3][4] The first director of the NRA was Hugh S. Johnson, a retired United States Army general who had been in charge of supervising the wartime economy in 1917–1918.

Historian Clarence B. Carson noted: At this moment in time from the early days of the New Deal, it is difficult to recapture, even in imagination, the heady enthusiasm among a goodly number of intellectuals for a government planned economy.

So far as can now be told, they believed that a bright new day was dawning, that national planning would result in an organically integrated economy in which everyone would joyfully work for the common good, and that American society would be freed at last from those antagonisms arising, as General Hugh Johnson put it, from "the murderous doctrine of savage and wolfish individualism, looking to dog-eat-dog and devil take the hindmost.

The NRA tried to get the principals to compromise with a national code for a decentralized industry in which many companies were anti-union, sought to keep wage differentials, and tried to escape the collective bargaining provisions of section 7A.

"[7] Of the 2,000 businessmen on hand probably 90% opposed Mr. Williams' aim, reported Time magazine: "To them a guaranteed price for their products looks like a royal road to profits.

[8] The business position was summarized by George A. Sloan, head of the Cotton Textile Code Authority: Maximum hours and minimum wage provisions, useful and necessary as they are in themselves, do not prevent price demoralization.

Destructive competition at the expense of employees is lessened, but it is left in full swing against the employer himself and the economic soundness of his enterprise....But if the partnership of industry with Government which was invoked by the President were terminated (as we believe it will not be), then the spirit of cooperation, which is one of the best fruits of the NRA equipment, could not survive.

[7]The Blue Eagle was a symbol used in the United States by companies to show compliance with and support of the National Industrial Recovery Act.

[12] In doing this, Roosevelt hoped that those stores which did not comply with the policies of the NRA would change their stance, or they would risk experiencing "economic death" as a result.

All companies that accepted President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Re-employment Agreement or a special Code of Fair Competition were permitted to display a poster showing the Blue Eagle together with the announcement, "NRA Member.

Shortly after the rules of the NRA were established, more than 10,000 businesses applied for the right to display the Blue Eagle in their store windows, by pledging their support to the program.

[31] The National Recovery Review Board, headed by noted criminal lawyer Clarence Darrow, a prominent liberal, was set up by President Roosevelt in March 1934 and abolished by him that same June.

"[33] Shouse said that he had "deep sympathy" with the goals of the NRA, explaining, "While I feel very strongly that the prohibition of child labor, the maintenance of a minimum wage and the limitation of the hours of work belong under our form of government in the realm of the affairs of the different states, yet I am entirely willing to agree that in the case of an overwhelming national emergency the Federal Government for a limited period should be permitted to assume jurisdiction of them.

"[34] The NRA negotiated specific sets of codes with leaders of the nation's major industries; the most important provisions were anti-deflationary floors below which no company would lower prices or wages, and agreements on maintaining employment and production.

[35] Donald Richberg, who soon replaced Johnson as the head of the NRA said: There is no choice presented to American business between intelligently planned and uncontrolled industrial operations and a return to the gold-plated anarchy that masqueraded as "rugged individualism."...

General Secretary Lucy Randolph Mason and her league relentlessly lobbied the NRA to make its regulatory codes just and fair for all workers and to eliminate explicit and de facto discrimination in pay, working conditions, and opportunities for reasons of sex, race, or union status.

Even after the demise of the NRA, the league continued campaigning for collective bargaining rights and fair labor standards at both federal and state levels.

Journalist Raymond Clapper reported that between 4,000 and 5,000 business practices were prohibited by NRA orders that carried the force of law, which were contained in some 3,000 administrative orders running to over 10 million pages, and supplemented by what Clapper said were "innumerable opinions and directions from national, regional and code boards interpreting and enforcing provisions of the act."

[41] Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes wrote for a unanimous Court in invalidating the industrial "codes of fair competition" which the NIRA enabled the President to issue.

7075, June 15, 1935, to facilitate its new role as a promoter of industrial cooperation and to enable it to produce a series of economic studies,[41] which the National Recovery Review Board was already doing.

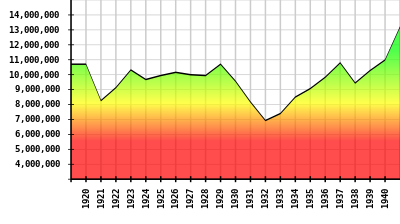

[49] Historian William E. Leuchtenburg argued in 1963: The NRA could boast some considerable achievements: it gave jobs to some two million workers; it helped stop a renewal of the deflationary spiral that had almost wrecked the nation; it did something to improve business ethics and civilize competition; it established a national pattern of maximum hours and minimum wages; and it all but wiped out child labor and the sweatshop.

Cursed at the time, it has remained the epitome of political aberration, illustrative of the pitfalls of “planning” and deplored both for hampering recovery and delaying genuine reform.