Blue duck

[9] Its taxonomic relationships with other waterfowl species remains uncertain; DNA analysis has placed it as a sister to the South American dabbling ducks (Anatini), but with no close relative.

[15] However, the populations were defined as distinct subspecies by the International Ornithological Congress in 2022, based on strong genetic divergence and some plumage differences.

[13][14][18] This species is an endemic resident breeder in New Zealand, nesting in hollow logs, small caves and other sheltered spots.

[20] Diving behaviour was seen most frequent in March and July when water levels are higher and prey living on stones and boulders above the water-surface would have been inaccessible using alternative foraging methods.

The reliance on these temporal patterns allows blue ducks to exploit a resource that is continuously recolonizing denuded areas in the river.

While foraging, blue ducks primarily glean invertebrates from rock surfaces using visual cues for mobile prey such as mayfly larvae.

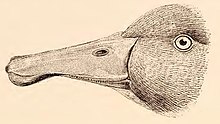

They have forward facing eyes that indicate this visual foraging use, typical of diving ducks, some attribute the evolution of this feature to the special absence of predators.

Although blue ducks occupy large territories, the size is not primarily determined by food abundance; rather, it reflects the overlapping life cycles of benthic invertebrates, which exhibit minimal seasonal variation.

[22] This indicates that while food resources are critical for blue duck distribution and population structure, they do not necessarily dictate territorial size.

Research indicates that pairs in higher-quality environments expend less energy on territorial defence, allowing for greater foraging opportunities and improved reproductive fitness.

Juvenile and unpaired blue ducks exploit these undefended spaces for foraging, indicating that territoriality does not completely limit resource availability for non-breeding individuals.

Most aggressive confrontations involve males defending territories against foraging intruders, highlighting male-male competition's role in shaping blue duck social dynamics.

[20][26] Blue ducks exhibit a complex social structure characterized by strong pair bonds and monogamous behaviour, integral to their reproductive success and territory defence in riverine habitats.

Typically, blue ducks maintain permanent year-round territories defended by mated pairs, emphasizing the significance of monogamy for the successful rearing of offspring.

During incubation, males shift their foraging habits to support female partners and their offspring, highlighting a collaborative approach to parental care.

[26] Although blue ducks generally exhibit monogamous pair bonding, instances of extra-pair mating may occur, particularly when environmental pressures or territory dynamics shift.

Nests are shallow, twig, grass and down-lined scrapes in caves, under river-side vegetation or in log-jams, and are therefore very prone to spring floods.

As part of this current ten-year plan (2009–2019) is the WHIONE programme which works with specially trained nose dogs to locate nests.

Early recovery efforts by scientists, field workers and volunteers have been summarised in a project sponsored by Genesis Energy, the Central North Island Blue Duck Charitable Conservation Trust and the Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society in 2006.

[31] In 2009 the New Zealand Department of Conservation started a ten-year recovery programme to protect the species at eight sites using predator control and then re-establish populations throughout their entire former range.

It will enable the implementation of a national recovery plan that will double the number of fully operational secure blue duck breeding sites throughout New Zealand, and boost pest control efforts.