Bodyline

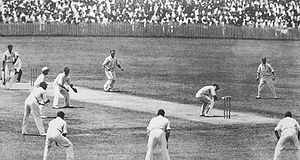

A bodyline delivery was one in which the cricket ball was bowled at pace, aimed at the body of the batsman in the expectation that when he defended himself with his bat, a resulting deflection could be caught by one of several fielders deliberately placed nearby on the leg side.

At the time, no helmets or other upper-body protective gear was worn, and critics of the tactic considered it intimidating, and physically threatening in a game traditionally supposed to uphold conventions of sportsmanship.

[2][3] Although no serious injuries arose from any short-pitched deliveries while a leg theory field was set, the tactic led to considerable ill feeling between the two teams, particularly when Australian batsmen were struck, inflaming spectators.

Over time, several Laws of Cricket were changed to render the bodyline tactic less effective—and increase player safety—such as a legside field restriction, concussion breaks and inspections.

The tactic involved bowling at the leg stump or just outside it, but pitching the ball short so that, on bouncing, it reared up threateningly at the body of a batsman standing in an orthodox batting position.

Other writers used a similar phrase around this time, but the first use of 'bodyline' in print seems to have been by the journalist Hugh Buggy in the Melbourne Herald, in his report on the first day's play of the first Test.

In 1925, Australian Jack Scott first bowled a form of what would later have been called bodyline in a state match for New South Wales; his captain Herbie Collins disliked it and would not let him use it again.

[20] In 1928–29, Harry Alexander bowled fast leg theory at an England team,[21] and Harold Larwood briefly used a similar tactic on that same tour in two Test matches.

Bradman was observed to be uncomfortable facing deliveries which bounced higher than usual at a faster pace, being seen to consistently step back out of the line of the ball.

[34][35] Jardine felt that Bradman was nervous about standing his ground against intimidatory bowling, citing instances in 1930 when he shuffled about, contrary to orthodox batting technique.

[38] When he scored three consecutive hundreds in the early games, he was frequently jeered by the crowd for slow play; the Australian spectators took an increasing dislike to him, mainly for his superior attitude and bearing, his awkward fielding, and particularly his choice of headwear—a Harlequin cap that was given to successful Oxford cricketers.

[39] Although Jardine may simply have worn the cap out of superstition, it conveyed a negative impression to the spectators; his general demeanour drew one comment of "Where's the butler to carry the bat for you?

[44] A meeting was arranged between Jardine, Nottinghamshire captain Arthur Carr and his two fast bowlers Harold Larwood and Bill Voce at London's Piccadilly Hotel to discuss a plan to combat Bradman.

[50] The England team which toured Australia in 1932–33 contained four fast bowlers and a few medium pacers; such a heavy concentration on pace was unusual at the time, and drew comment from the Australian press and players, including Bradman.

[73][notes 2] The only Australian batsman to make an impact was Stan McCabe, who hooked and pulled everything aimed at his upper body,[75] to score 187 not out in four hours from 233 deliveries.

[76] Meanwhile, Woodfull was being encouraged to retaliate to the short-pitched English attack, not least by members of his own side such as Vic Richardson, or to include pace bowlers such as Eddie Gilbert or Laurie Nash to match the aggression of the opposition.

However, when Larwood was ready to bowl at Woodfull again, play was halted once more when the fielders were moved into bodyline positions, causing the crowd to protest and call abuse at the England team.

[92] The fury of the crowd was such that a riot might have occurred had another incident taken place and several writers suggested that the anger of the spectators was the culmination of feelings built up over the two months that bodyline had developed.

Oldfield staggered away and fell to his knees and play stopped as Woodfull came onto the pitch and the angry crowd jeered and shouted, once more reaching the point where a riot seemed likely.

[110] At the end of the fourth day's play of the third Test match, the Australian Board of Control sent a cable to the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), cricket's ruling body and the club that selected the England team, in London: Australian Board of Control to MCC, January 18, 1933: Bodyline bowling assumed such proportions as to menace best interests of game, making protection of body by batsmen the main consideration.

We hope the situation is not now as serious as your cable would seem to indicate, but if it is such as to jeopardise the good relations between English and Australian cricketers, and you would consider it desirable to cancel remainder of programme, we would consent with great reluctance.

[2] The Governor of South Australia, Alexander Hore-Ruthven, who was in England at the time, expressed his concern to British Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs James Henry Thomas that this would cause a significant impact on trade between the nations.

[126][127] Voce returned for the final Test, but neither he nor Allen were fully fit,[128] and despite the use of bodyline tactics, Australia scored 435 at a rapid pace, aided by several dropped catches.

[129] Australia included a fast bowler for this final game, Harry Alexander who bowled some short deliveries but was not allowed to use many fielders on the leg side by his captain, Woodfull.

[150][151] Of the four fast bowlers in the tour party, Gubby Allen was a voice of dissent in the English camp, refusing to bowl short on the leg side,[147] and writing several letters home to England critical of Jardine, although he did not express this in public in Australia.

[8][153] Jardine however insisted his tactic was not designed to cause injury and that he was leading his team in a sportsmanlike and gentlemanly manner, arguing that it was up to the Australian batsmen to play their way out of trouble.

[157] Douglas Jardine always defended his tactics and in the book he wrote about the tour, In Quest of the Ashes, described allegations that the England bowlers directed their attack with the intention of causing physical harm as stupid and patently untruthful.

[158] The immediate effect of the law change which banned bodyline in 1935 was to make commentators and spectators sensitive to the use of short-pitched bowling; bouncers became exceedingly rare and bowlers who delivered them were practically ostracised.

[165] The series took some liberties with historical accuracy for the sake of drama, including a depiction of angry Australian fans burning a British flag at the Adelaide Oval, an event which was never documented.

[165] Larwood, having emigrated to Australia in 1950, was largely welcomed with open arms, although received several threatening and obscene phone calls after the series aired.