Bombing of Tokyo

Second Sino-Japanese War The bombing of Tokyo (東京空襲, Tōkyō kūshū) was a series of air raids on Japan launched by the United States Army Air Forces during the Pacific Theatre of World War II in 1944–1945, prior to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

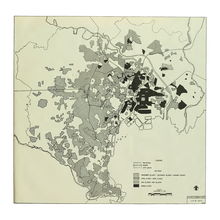

[1] 16 square miles (41 km2; 10,000 acres) of central Tokyo was destroyed, leaving an estimated 100,000 civilians dead and over one million homeless.

[6] Launched at longer range than planned when the task force encountered a Japanese picket boat, all of the attacking aircraft either crashed or ditched short of the airfields designated for landing.

[7][8] The key development for the bombing of Japan was the B-29 Superfortress strategic bomber, which had an operational range of 3,250 nautical miles (3,740 mi; 6,020 km) and was capable of attacking at high altitude above 30,000 feet (9,100 m), where enemy defenses were very weak.

[11] Between May and September 1943, bombing trials were conducted on the Japanese Village set-piece target, located at the Dugway Proving Grounds.

[12] These trials demonstrated the effectiveness of incendiary bombs against wood-and-paper buildings, and resulted in Curtis LeMay's ordering the bombers to change tactics to utilize these munitions against Japan.

The M-69s punched through thin roofing material or landed on the ground; in either case they ignited 3–5 seconds later, throwing out a jet of flaming napalm globs.

[17] The first B-29s to arrive dropped bombs in a large X pattern centered in Tokyo's densely populated working class district near the docks in both Koto and Chūō city wards on the water; later aircraft simply aimed near this flaming X.

The individual fires caused by the bombs joined to create a general conflagration, which would have been classified as a firestorm but for prevailing winds gusting at 17 to 28 mph (27 to 45 km/h).

[19][20] A grand total of 282 of the 339 B-29s launched for "Meetinghouse" made it to the target, 27 of which were lost due to being shot down by Japanese air defenses, mechanical failure, or being caught in updrafts caused by the fires.

According to the victorious US report, over 50% of Tokyo's industry was spread out among residential and commercial neighborhoods; firebombing cut the whole city's output in half.

[26] Emperor Hirohito's tour of the destroyed areas of Tokyo in March 1945 was the beginning of his involvement in the peace process, culminating in Japan's surrender six months later.

[27] The US Strategic Bombing Survey later estimated that nearly 88,000 people died in this one raid, 41,000 were injured, and over a million residents lost their homes.

[29] These casualty and damage figures could be low; Mark Selden wrote in Japan Focus: The figure of roughly 100,000 deaths, provided by Japanese and American authorities, both of whom may have had reasons of their own for minimizing the death toll, seems to be arguably low in light of population density, wind conditions, and survivors' accounts.

Occupation authorities such as Joseph Dodge stepped in and drastically cut back on Japanese government rebuilding programs, focusing instead on simply improving roads and transportation.

[40] In 2007, 112 members of the Association for the Bereaved Families of the Victims of the Tokyo Air Raids brought a class action against the Japanese government, demanding an apology and 1.232 billion yen in compensation.

"By the end of 17 February, more than five hundred Japanese planes, both on the ground and in the air, had been lost, and Japan's aircraft works had been badly hit.

The B-32 piloted by 1st Lt. John R. Anderson, was hit at 20,000 feet; cannon fire knocked out the number two (port inner) engine, and three crew were injured, including Sgt.