Bonobo

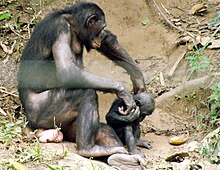

[5][6] Bonobos are distinguished from common chimpanzees by relatively long limbs, pinker lips, a darker face, a tail-tuft through adulthood, and parted, longer hair on their heads.

It is predominantly frugivorous,[7] compared to the often highly omnivorous diets and hunting of small monkeys, duiker and other antelope exhibited by common chimpanzees.

[4] As the two species are not proficient swimmers, the natural formation of the Congo River (around 1.5–2 million years ago) possibly led to the isolation and speciation of the bonobo.

The name "pygmy" was given by the German zoologist Ernst Schwarz in 1929, who classified the species on the basis of a previously mislabeled bonobo cranium, noting its diminutive size compared to chimpanzee skulls.

[11] The name "bonobo" first appeared in 1954, when Austrian zoologist Eduard Paul Tratz and German biologist Heinz Heck proposed it as a new and separate generic term for pygmy chimpanzees.

[12][13] The bonobo was first recognised as a distinct taxon in 1928 by German anatomist Ernst Schwarz, based on a skull in the Tervuren Museum in Belgium which had previously been classified as a juvenile chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes).

[16] Unaware of any taxonomic distinction with the common chimpanzee, American psychologist and primatologist Robert Yerkes had already noticed an unexpected major behavioural difference in the 1920s.

[8][9] Nonetheless, the exact timing of the Pan–Homo last common ancestor is contentious, but DNA comparison suggests continual interbreeding between ancestral Pan and Homo groups, post-divergence, until about 4 million years ago.

[20] DNA evidence suggests the bonobo and common chimpanzee species diverged approximately 890,000–860,000 years ago following separation of these two populations possibly because of acidification and the spread of savannas at this time.

[24] According to Australian anthropologists Gary Clark and Maciej Henneberg, human ancestors went through a bonobo-like phase featuring reduced aggression and associated anatomical changes, exemplified in Ardipithecus ramidus.

[31] In modern times hybridization between bonobos and chimpanzees in the wild is prevented as populations are allopatric and kept isolated on different sides of the Congo river.

[57][58] At the top of the hierarchy is a coalition of high-ranking females and males typically headed by an old, experienced matriarch[59] who acts as the decision-maker and leader of the group.

[76] A mother bonobo will also support her grown son in conflicts with other males and help him secure better ties with other females, enhancing her chance of gaining grandchildren from him.

[89] In wild settings, however, female bonobos will quietly ask males for food if they had gotten it first, instead of forcibly confiscating it, suggesting sex-based hierarchy roles are less rigid than in captive colonies.

Another form of genital interaction (rump rubbing) often occurs to express reconciliation between two males after a conflict, when they stand back-to-back and rub their scrotal sacs together, but such behavior also occurs outside agonistic contexts: Kitamura (1989) observed rump–rump contacts between adult males following sexual solicitation behaviors similar to those between female bonobos prior to GG-rubbing.

[109] Compared to common chimpanzees, bonobo females resume the genital swelling cycle much sooner after giving birth, enabling them to rejoin the sexual activities of their society.

[50] It has been hypothesized that bonobos are able to live a more peaceful lifestyle in part because of an abundance of nutritious vegetation in their natural habitat, allowing them to travel and forage in large parties.

[126] They also have a thick connection between the amygdala, an important area that can spark aggression, and the ventral anterior cingulate cortex, which has been shown to help control impulses in humans.

The bonobo is an omnivorous frugivore; 57% of its diet is fruit, but this is supplemented with leaves, honey, eggs,[134] meat from small vertebrates such as anomalures, flying squirrels and duikers,[135] and invertebrates.

[142] In 2020, the first whole-genome comparison between chimpanzees and bonobos was published and showed genomic aspects that may underlie or have resulted from their divergence and behavioral differences, including selection for genes related to diet and hormones.

[144] A 2010 study found that "female bonobos displayed a larger range of tool use behaviours than males, a pattern previously described for chimpanzees but not for other great apes".

[150] Two bonobos at the Great Ape Trust, Kanzi and Panbanisha, have been taught how to communicate using a keyboard labeled with lexigrams (geometric symbols) and they can respond to spoken sentences.

Some, such as philosopher and bioethicist Peter Singer, argue that these results qualify them for "rights to survival and life"—rights which humans theoretically accord to all persons (See great ape personhood).

[153] As in other great apes and humans, third party affiliation toward the victim—the affinitive contact made toward the recipient of an aggression by a group member other than the aggressor—is present in bonobos.

This model, implemented mainly through DRC organizations and local communities, has helped bring about agreements to protect over 50,000 square miles (130,000 km2) of the bonobo habitat.

This program includes habitat and rain-forest preservation, training for Congolese nationals and conservation institutions, wildlife population assessment and monitoring, and education.

They have built schools, hired teachers, provided some medicines, and started an agriculture project to help the Congolese learn to grow crops and depend less on hunting wild animals.

[172] With grants from the United Nations, USAID, the U.S. Embassy, the World Wildlife Fund, and many other groups and individuals, the ZSM also has been working to: Starting in 2003, the U.S. government allocated $54 million to the Congo Basin Forest Partnership.

This significant investment has triggered the involvement of international NGOs to establish bases in the region and work to develop bonobo conservation programs.

This initiative should improve the likelihood of bonobo survival, but its success still may depend upon building greater involvement and capability in local and indigenous communities.