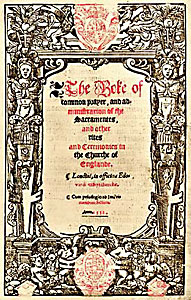

Book of Common Prayer (1552)

The first Book of Common Prayer was issued in 1549 as part of the English Reformation, but Protestants criticised it for being too similar to traditional Roman Catholic services.

During the reign of Mary I, Roman Catholicism was restored, and the prayer book's official status was repealed.

When Elizabeth I reestablished Protestantism as the official religion, the 1559 Book of Common Prayer—a revised version of the 1552 prayer book—was issued as part of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement.

Compiled by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, the prayer book was a Protestant liturgy meant to replace the Roman Rite.

In the prayer book, the Latin Mass—the central act of medieval worship—was replaced with an English-language communion service.

Priests were still required to wear traditional vestments, such as the cope, and they continued to celebrate the Eucharist on stone altars.

[5] Conservative clergy used the prayer book's traditional features to make the liturgy resemble the Latin Mass, and this led Protestants both in England and abroad to criticise it for being susceptible to Roman Catholic re-interpretation.

[10] Martyr's recommendations are now lost, but he wrote an exhortation to receive communion that was incorporated into the new prayer book.

[11] In April 1552, Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity that authorised the revised Book of Common Prayer to be used in worship by All Saints' Day, November 1.

At the time, Cranmer felt that gradual change was the best approach "lest the people, not having yet learned Christ, should be deterred by too extensive innovations from embracing his religion".

[10] By 1551, conservative opposition had been removed, and the 1552 Prayer Book "broke decisively with the past" in the words of historian Christopher Haigh.

[10] Unlike the 1549 version, the 1552 prayer book removed many traditional sacramentals and observances that reflected belief in the blessing and exorcism of people and objects.

It also reintroduced Lammas Day, which had originally commemorated the liberation of Saint Peter but in England was an agricultural festival.

[15] The following saints were commemorated:[17][18] The calendar included what is now called the lectionary, which specified the parts of the Bible to be read at each service.

[22] The name of the service was changed to "The Order for the Administration of the Lord's Supper or Holy Communion", removing the word Mass.

Stone altars were replaced with communion tables positioned in the chancel or nave, with the priest standing on the north side.

[27] The theme of lifting up hearts to God appealed to the Reformed belief in meeting Christ spiritually in heaven.

Rather, the priest prayed that the communicants might receive the body and blood of Christ:[23] Almighty God, our heavenly Father, which of thy tender mercy didst give thine only Son Jesus Christ to suffer death upon the Cross for our redemption; who made there (by his one oblation of himself once offered) a full, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction for the sins of the whole world; and did institute, and in his holy Gospel command us to continue a perpetual memory of that his precious death, until his coming again; Hear us, O merciful Father, we beseech thee; and grant that we receiving these thy creatures of bread and wine, according to thy Son our Saviour Jesu Christ's holy institution, in remembrance of his death and passion, may be partakers of his most blessed body and blood .

In agreement with Reformed theology, however, Cranmer believed that salvation was determined by God's unconditional election, which was predestined.

The priest began with this exhortation: Dearly beloved, for as much as all men be conceived and born in sin, and that our Saviour Christ saith, none can enter into the kingdom of God (except he be regenerate and born anew of water and the holy Ghost); I beseech you to call upon God the father through our Lord Jesus Christ, that of his bounteous mercy, he will grant to these children, that thing which by nature they cannot have, that they may be Baptized with water and the holy ghost, and received into Christ's holy church, and be made lively members of the same.

[34]The congregation then prayed "Receive [these infants] (O Lord) as thou hast promised by thy well beloved son, ... that these infants may enjoy the everlasting benediction of thy heavenly washing, and may come to the eternal Kingdom which thou hast promised by Christ our Lord.

[32] The theme of God receiving the child continued with the gospel reading (Mark 10) and the minister's exhortation, which was probably intended to repudiate Anabaptist teachings against infant baptism.

[32] The congregation then prayed that the baptismal candidates receive the Holy Spirit:[36] Almighty and everlasting God, heavenly father, we give thee humble thanks, that thou hast vouchsafed to call us to the knowledge of thy grace, and faith in thee: increase this knowledge, and confirm this faith in us evermore: Give thy holy spirit to these infants, that they may be born again, and be made heirs of everlasting salvation, through our Lord Jesus Christ: who liveth and reigneth with thee and the holy spirit, now and for ever.

[36] This was followed by a series of prayers taken from the blessing of the font in the 1549 book (which was omitted in the new book),[35] ending as follows: Almighty ever living God, whose most dearly beloved son Jesus Christ, for the forgiveness of our sins, did shed out of his most precious side both water and blood, and gave commandment to his disciples that they should go teach all nations, and baptize them in the name of the father, the son, and of the holy ghost: Regard, we beseech thee, the supplications of thy congregation, and grant that all thy servants which shall be baptized in this water, may receive the fullness of thy grace, and ever remain in the number of thy faithful and elect children, through Jesus Christ our Lorde.

The Latin Mass was re-established, altars, roods and statues of saints were reinstated in an attempt to restore the English Church to its Roman affiliation.

A bitter and very public dispute ensued between those, such as Edmund Grindal and Richard Cox, who wished to preserve in exile the exact form of worship of the 1552 Prayer Book, and those, such as John Knox the minister of the congregation, who regarded that book as still partially tainted with compromise (see Troubles at Frankfurt).

[41] Consequently, when the accession of Elizabeth I re-asserted the dominance of the Reformed Church of England, there remained a significant body of more Protestant believers who were nevertheless hostile to the Book of Common Prayer.