Book of Common Prayer (1662)

Noted for both its devotional and literary quality, the 1662 prayer book has influenced the English language, with its use alongside the King James Version of the Bible contributing to an increase in literacy from the 16th to the 20th century.

Its contents have inspired or been adapted by many Christian movements spanning multiple traditions both within and outside the Anglican Communion, including Anglo-Catholicism, Methodism, Western Rite Orthodoxy, and Unitarianism.

[5] Due to its dated language and lack of specific offices for modern life, the 1662 prayer book has largely been supplanted for public liturgies within the Church of England by Common Worship.

The 1559 edition was for some time the second-most diffuse book in England, only behind the Bible, through an act of Parliament that mandated its presence in each parish church across the country.

Further escalating the tension between Puritans and other factions in the Church of England were efforts, such as those by Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury, to require the usage of certain vestments such as the surplice and cope.

[8]: 73 Among the more notable alterations in the Jacobean prayer book was an elongation of the Catechism's sacramental teachings and the introduction of a rubric allowing only a "lawful minister" to perform baptisms, which has been described as an example of post-Reformation clericalism.

[16] The popular Puritan Root and Branch petition, presented to the Long Parliament by Oliver Cromwell and Henry Vane the Younger in 1640, attempted to eliminate the episcopacy and decried the prayer book as "Romish".

[8]: 77 This desire for effective revision was contemporaneous with a significant increase of interest in Anglican liturgical history; Hamon L'Estrange's 1659 The alliance of divine offices would be the only comparative study of the preceding prayer books for some time even following the 1662 edition's approval.

[21] The conference terminated with few concessions to the Puritans, which included rejecting an effort to delete the wedding ring from the marriage office, and encouraged the creation of a new prayer book.

[26] The post-Puritan Parliament passed a series of four laws, known as the Clarendon Code, to prevent Puritans and other Nonconformists from holding office and ensure that public worship was according to officially approved Anglican texts.

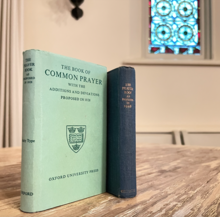

[32]: x It was during the first decades of the 1662 edition's use that Oxford University Press began printing an increasingly larger proportion of the total number of prayer books produced.

[36]: 61 With the leadership of William Lloyd, then the Bishop of Worcester, and deans Edward Stillingfleet, Simon Patrick, and John Tillotson (the latter becoming the Archbishop of Canterbury), a revised prayer book was produced in 1689.

[54]: 6–7 This text was submitted to the House of Commons as required by law, where it was defeated in December 1927 after a coalition of conservative Church of England loyalists and Nonconformists failed to override both opposition and Catholic parliamentarian abstention.

Among those in favour of approval had been Winston Churchill, who affirmed the Church of England's Protestant orthodoxy, while opponents viewed the proposed text as too permissive of "indiscipline and Romanism".

[60]: 265 The acceptance of these new rites saw several failed attempts in the House of Lords to limit the alternative texts, including requirements that parishes offer a certain proportion of their liturgies according to the 1662 prayer book.

The amended 1662 version revised the rubric to disallow viewing the consecration of the Eucharist as a "corporal" change, permitting a limited theology of the real presence.

[65]: 126 The 1958 Lambeth Conference's Prayer Book Committee recommended psalms for the Introit and Gradual; metrical hymns were also generally accepted for both portions of the Communion office.

[77]: x By this point, though, the 1662 prayer book's Daily Office faced criticism as insufficiently reflective of Reformation desires for public celebration of the canonical hours.

[13]: 99 The 1662 matrimonial office remains a legal option to solemnise marriages in the Church of England, and a modified form known as Alternative Services: Series One that is also partially derived from the 1928 proposed prayer book was latterly adopted.

The historian Brian Cummings described the prayer book as sometimes "beckoning to a treasured Englishness as stereotyped by rain or hedgerows, dry-stone walls or terraced housing, Brief Encounter or Wallace and Gromit.

[88] Charlotte Brontë's copy of the 1662 prayer book, gifted by her future husband Arthur Bell Nicholls and later acquired by Francis Jenkinson, resides in Cambridge University Library's special collections.

While introduced to the English language by William Tyndale's translation of the Greek word ἀγαπητός (agapétos) for his production of the Bible, as well as subsequent versions produced by Myles Coverdale, the phrase attained popularity after its inclusion in the 1662 prayer book.

William III established Presbyterianism as the faith of the Church of Scotland in 1690, leaving the disestablished Scottish Episcopalians to seek printings of the 1662 prayer book to continue their worship.

[92]: 59 The resulting 1718 Nonjuror Office[note 9] introduced an epiclesis, or invocation of the Holy Spirit over the bread and wine during the prayer of consecration, a reflection of West Syriac and Byzantine influence.

[98]: 312 [note 11] The Church of India, Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon, a since dissolved denomination, saw an extended period of revision due to the involvement of an Evangelical faction rather than Anglo-Catholic hegemony, approving a new prayer book in 1960.

The 1904 response from the Russian Orthodox synod reviewing of the 1662 and later U.S. Episcopal Church prayer books found deficiencies in the manner and theology of the liturgies, though opened the door to permitting a revised version.

[5] Kallistos Ware, a convert to Eastern Orthodoxy from Anglicanism with a personal familiarity with the 1662 prayer book, opted against the Western Rite but retained 17th-century English lexicon for his translations of the Festal Menaion and the Lenten Triodion.

[128] Despite his affinity for the prayer book, Wesley desired to adjust its liturgies and rubrics to maximise evangelisation and better reflect his view of Scriptural and early apostolic practises.

[129] Among Wesley's grievances with the prayer book, voiced in a 1755 essay supporting remaining within the Church of England, were the inclusion of the Athanasian Creed, sponsors at baptism, and the "essential difference" between bishops and presbyters.

[130] Influences on Wesley's liturgy included Puritans and Samuel Clarke's work to alter the 1662 prayer book, as compiled and implemented by Theophilus Lindsey for his Essex Street Chapel congregation.