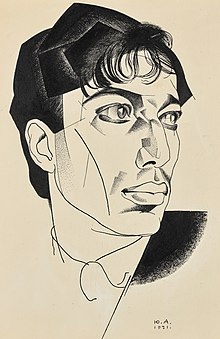

Boris Pasternak

Pasternak's translations of stage plays by Goethe, Schiller, Calderón de la Barca and Shakespeare remain very popular with Russian audiences.

After World War One and the Revolution, fighting for the Provisional or Republican government under Kerensky, and then escaping a Communist jail and execution, Minchakievich trekked across Siberia in 1917 and became an American citizen.

In a 1959 letter to Jacqueline de Proyart, Pasternak recalled: I was baptized as a child by my nanny, but because of the restrictions imposed on Jews, particularly in the case of a family which was exempt from them and enjoyed a certain reputation in view of my father's standing as an artist, there was something a little complicated about this, and it was always felt to be half-secret and intimate, a source of rare and exceptional inspiration rather than being calmly taken for granted.

Most intensely of all my mind was occupied by Christianity in the years 1910–12, when the main foundations of this distinctiveness—my way of seeing things, the world, life—were taking shape...[7]Shortly after his birth, Pasternak's parents had joined the Tolstoyan Movement.

[15] The action eventually caused a verbal battle amongst several members of the groups, fighting for recognition as the first, truest Russian Futurists; these included the Cubo-Futurists, who were by that time already notorious for their scandalous behaviour.

According to Max Hayward, Pasternak remained in Moscow throughout the Civil War (1918–1920), making no attempt to escape abroad or to the White-occupied south, as a number of other Russian writers did at the time.

In a letter written to Pasternak from abroad in the twenties, Marina Tsvetayeva reminded him of how she had run into him in the street in 1919 as he was on the way to sell some valuable books from his library in order to buy bread.

By 1927, Pasternak's close friends Vladimir Mayakovsky and Nikolai Aseyev were advocating the complete subordination of the arts to the needs of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Although its Caucasian pieces were as brilliant as the earlier efforts, the book alienated the core of Pasternak's refined audience abroad, which was largely composed of anti-communist émigrés.

[24] According to Pasternak, during the 1937 show trial of General Iona Yakir and Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, the Union of Soviet Writers requested all members to add their names to a statement supporting the death penalty for the defendants.

Then, an end to the war in favour of our allies, civilized countries with democratic traditions, would have meant a hundred times less suffering for our people than that which Stalin again inflicted on it after his victory.

The critic accused Pasternak of distorting Goethe's "progressive" meanings to support the reactionary theory of 'pure art', as well as introducing aesthetic and individualist values.

In a subsequent letter to the daughter of Marina Tsvetaeva, Pasternak explained that the attack was motivated by the fact that the supernatural elements of the play, which Novy Mir considered, "irrational", had been translated as Goethe had written them.

[44] The Soviet government forced Pasternak to cable the publisher to withdraw the manuscript, but he sent separate, secret letters advising Feltrinelli to ignore the telegrams.

[49] On 9 September 1958, the Literary Gazette critic Viktor Pertsov retaliated by denouncing the decadent religious poetry of Pasternak, which reeks of mothballs from the Symbolist suitcase of 1908–10 manufacture.

[59] According to Solomon Volkov: The anti-Pasternak campaign was organized in the worst Stalin tradition: denunciations in Pravda and other newspapers; publications of angry letters from, "ordinary Soviet workers", who had not read the book; hastily convened meetings of Pasternak's friends and colleagues, at which fine poets like Vladimir Soloukin, Leonid Martynov, and Boris Slutsky were forced to censure an author they respected.

On October 29, 1958, at the plenum of the Central Committee of the Young Communist League, dedicated to the Komsomol's fortieth anniversary, its head, Vladimir Semichastny, attacked Pasternak before an audience of 14,000 people, including Khrushchev and other Party leaders.

As a result, on 29 October Pasternak sent a second telegram to the Nobel Committee: In view of the meaning given the award by the society in which I live, I must renounce this undeserved distinction which has been conferred on me.

After all that had happened, open shadowing, friends turning away, Pasternak's suicidal condition at the time, one can... understand her: the memory of Stalin's camps was too fresh, [and] she tried to protect him.

[69] During the summer of 1959, Pasternak began writing The Blind Beauty, a trilogy of stage plays set before and after Alexander II's abolition of serfdom in Russia.

He informed Olga Carlisle that, at the end of The Blind Beauty, he wished to depict "the birth of an enlightened and affluent middle class, open to occidental influences, progressive, intelligent, artistic".

According to her, He began to say what an authentic event the funeral was—an expression of what people really felt, and so characteristic of the Russia which stoned its prophets and did its poets to death as a matter of longstanding tradition.

The Russian TV version of 2006, directed by Aleksandr Proshkin and starring Oleg Menshikov as Zhivago, is considered [citation needed] more faithful to Pasternak's novel than David Lean's 1965 film.

According to Olga Ivinskaya: In Pasternak the "all-powerful god of detail" always, it seems, revolted against the idea of turning out verse for its own sake or to convey vague personal moods.

[Boris Leonidovich] could weep over the "purple-gray circle" which glowed above Blok's tormented muse and he never failed to be moved by the terseness of Pushkin's sprightly lines, but rhymed slogans about the production of tin cans in the so-called "poetry" of Surkov and his like, as well as the outpourings about love in the work of those young poets who only echo each other and the classics—all this left him cold at best and for the most part made him indignant.

He soon produced acclaimed translations of Sándor Petőfi, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Rainer Maria Rilke, Paul Verlaine, Taras Shevchenko, and Nikoloz Baratashvili.

[109] According to Ivinskaya: Whenever [Boris Leonidovich] was provided with literal versions of things which echoed his own thoughts or feelings, it made all the difference and he worked feverishly, turning them into masterpieces.

[110]While they were both collaborating on translating Rabindranath Tagore from Bengali into Russian, Pasternak advised Ivinskaya: "1) Bring out the theme of the poem, its subject matter, as clearly as possible; 2) tighten up the fluid, non-European form by rhyming internally, not at the end of the lines; 3) use loose, irregular meters, mostly ternary ones.

He came from a musical family: his mother was a concert pianist and a student of Anton Rubinstein and Theodor Leschetizky, and Pasternak's early impressions were of hearing piano trios in the home.

The high achievements of his mother discouraged him from becoming a pianist, but – inspired by Scriabin – he entered the Moscow Conservatory, but left abruptly in 1910 at the age of twenty, to study philosophy in Marburg University.