Boshin War

The defeat at the Battle of Hakodate broke this last holdout and left the Emperor as the de facto supreme ruler throughout the whole of Japan, completing the military phase of the Meiji Restoration.

In the end, the victorious Imperial faction abandoned its objective of expelling foreigners from Japan and instead adopted a policy of continued modernization with an eye to the eventual renegotiation of the unequal treaties with the Western powers.

Since Western nations, especially the United Kingdom and France, were deeply involved in the country's politics, the installation of Imperial power added more turbulence to the conflict.

[5] For the two centuries prior to 1854, Japan had a strict policy of isolationism, restricting all interactions with foreign powers, with the notable exceptions of Korea via Tsushima, Qing China via the Ryukyu Islands, and the Dutch through the trading post of Dejima.

[a] In 1854, the United States Navy Commodore Matthew C. Perry's expedition opened Japan to global commerce through the implied threat of force, thus initiating rapid development of foreign trade and Westernization.

In large part due to the humiliating terms of the unequal treaties, as agreements like those negotiated by Perry are called, the Tokugawa shogunate soon faced internal dissent, which coalesced into a radical movement, the sonnō jōi (meaning "revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians").

[10] Emperor Kōmei agreed with such sentiments and, breaking with centuries of Imperial tradition, began to take an active role in matters of state: as opportunities arose, he vehemently protested against the treaties and attempted to interfere in the shogunal succession.

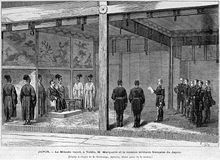

[c] The British ambassador, Harry Smith Parkes, supported the anti-shogunate forces in a drive to establish a legitimate, unified Imperial rule in Japan, and to counter French influence with the shogunate.

During that period, southern Japanese leaders such as Saigō Takamori of Satsuma, or Itō Hirobumi and Inoue Kaoru of Chōshū cultivated personal connections with British diplomats, notably Ernest Mason Satow.

[f] The shogunate took major steps towards the construction of a modern and powerful military: a navy with a core of eight steam warships had been built over several years and was already the strongest in Asia.

In January 1867, a French military mission arrived to reorganize the shogunate army and create the Denshūtai elite force, and an order was placed with the US to buy the French-built ironclad warship CSS Stonewall,[22] which had been built for the Confederate States Navy during the American Civil War.

[29][30] Satow speculated that Yoshinobu had agreed to an assembly of daimyōs on the hope that such a body would restore him,[31] a prospect hard-liners from Satsuma and Chōshū found intolerable.

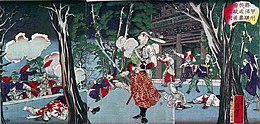

[32] Events came to a head on January 3, 1868, when these elements seized the imperial palace in Kyoto, and the following day had the fifteen-year-old Emperor Meiji declare his own restoration to full power.

[37] The shōgun also relied on troops supplied by allied domains, which were not necessarily as advanced in terms of military equipment and methods, composing an army that had both modern and outdated elements.

[44] Imperial troops mainly used Minié rifles, which were much more accurate, lethal, and had a much longer range than the imported smoothbore muskets, although, being also muzzle-loading, they were similarly limited to two shots per minute.

Improved breech-loading mechanisms, such as the Snider, developing a rate of about ten shots a minute, are known to have been used by Chōshū troops against the shogunate's Shōgitai regiment at the Battle of Ueno in July 1868.

The ship was blocked from delivery by foreign powers on grounds of neutrality once the conflict had started, and was ultimately delivered to the Imperial faction shortly after the Battle of Toba–Fushimi.

[34] After the defections, Yoshinobu, apparently distressed by the imperial approval given to the actions of Satsuma and Chōshū, fled Osaka aboard the Japanese battleship Kaiyō Maru, withdrawing to Edo.

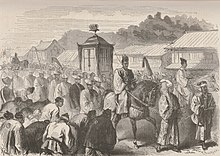

A few days later however an Imperial delegation visited the ministers declaring that the shogunate was abolished, that harbours would be open in accordance with International treaties, and that foreigners would be protected.

In early March, under the influence of the British minister Harry Parkes, foreign nations signed a strict neutrality agreement, according to which they could not intervene or provide military supplies to either side until the resolution of the conflict.

[m] On the other hand, the daimyō of Nagaoka managed to procure two of the three Gatling guns in Japan and 2,000 modern French rifles from the German weapons dealer Henry Schnell.

The battle ended in failure for the Tokugawa side, owing to bad weather, engine trouble and the decisive use of a Gatling gun by Imperial troops against samurai boarding parties.

[72] Invited to surrender, Enomoto at first refused, and sent the Naval Codes he had brought back from Holland to the general of the Imperial troops, Kuroda Kiyotaka, to prevent their loss.

[q] The southern domains of Satsuma, Chōshū and Tosa, having played a decisive role in the victory, occupied most of the key posts in government for several decades following the conflict, a situation sometimes called the "Meiji oligarchy" and formalized with the institution of the genrō.

He had urged Saigō, in the words of Ernest Satow, "that severity towards Keiki [Yoshinobu] or his supporters, especially in the way of personal punishment, would injure the reputation of the new government in the opinion of European Powers".

A high level of interaction resumed around 1886, when France helped build the Imperial Japanese Navy's first large-scale modern fleet, under the direction of naval engineer Louis-Émile Bertin.

[87][88] Upon his coronation, Meiji issued his Charter Oath, calling for deliberative assemblies, promising increased opportunities for the common people, abolishing the "evil customs of the past", and seeking knowledge throughout the world "to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule".

When faced with the Hull note, they believed war was inevitable and launched the attack on Pearl Harbor without considering the long-term consequences, ultimately leading to a devastating defeat.

The facts of the Boshin War, however, clearly show that the conflict was quite violent: about 120,000 troops were mobilized altogether with roughly 3,500 known casualties during open hostilities but much more during terrorist attacks.

Western interpretations include the 2003 American film The Last Samurai directed by Edward Zwick, which combines into a single narrative historical situations belonging both to the Boshin War, the 1877 Satsuma Rebellion, and other similar uprisings of ex-samurai during the early Meiji period.