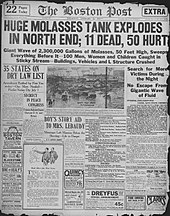

Great Molasses Flood

[5][6] The wave was of sufficient force to drive steel panels of the burst tank against the girders of the adjacent Boston Elevated Railway's Atlantic Avenue structure[11] and tip a streetcar momentarily off the El's tracks.

Puleo quotes a Boston Post report: Molasses, waist deep, covered the street and swirled and bubbled about the wreckage [...] Here and there struggled a form—whether it was animal or human being was impossible to tell.

Edwards Park wrote of one child's experience in a 1983 article for Smithsonian: Anthony di Stasio, walking homeward with his sisters from the Michelangelo School, was picked up by the wave and carried, tumbling on its crest, almost as though he were surfing.

[13] The cadets ran several blocks toward the accident and entered into the knee-deep flood of molasses to pull out the survivors, while others worked to keep curious onlookers from getting in the way of the rescuers.

Rescuers found it difficult to make their way through the syrup to help the victims, and four days elapsed before they stopped searching; many of the dead were so glazed over in molasses that they were hard to recognize.

[12] In the wake of the accident, 119 residents brought a class-action lawsuit against the United States Industrial Alcohol Company (USIA),[14] which had bought Purity Distilling in 1917.

[18] The cleanup in the immediate area took weeks,[19] with several hundred people contributing to the effort,[7]: 132–134, 139 [15] and it took longer to clean the rest of Greater Boston and its suburbs.

Rescue workers, cleanup crews, and sight-seers had tracked molasses through the streets and spread it to subway platforms, to the seats inside trains and streetcars, to pay telephone handsets, into homes,[6][7]: 139 and to countless other places.

[27] A 2014 investigation applied modern engineering analysis and found that the steel was half as thick as it should have been for a tank of its size even with the lower standards they had at the time.

[5] In 2016, a team of scientists and students at Harvard University conducted extensive studies of the disaster, gathering data from many sources, including 1919 newspaper articles, old maps, and weather reports.

When the tank collapsed, the fluid cooled quickly as it spread, until it reached Boston's winter evening temperatures and the viscosity increased dramatically.

[31] The Harvard study concluded that the molasses cooled and thickened quickly as it rushed through the streets, hampering efforts to free victims before they suffocated.

The property formerly occupied by the molasses tank and the North End Paving Company became a yard for the Boston Elevated Railway (predecessor to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority).

It is now the site of a city-owned recreational complex, officially named Langone Park, featuring a Little League Baseball field, a playground, and bocce courts.

Structural defects in the tank combined with unseasonably warm temperatures contributed to the disaster.The accident has since become a staple of local culture, not only for the damage the flood brought, but also for the sweet smell that filled the North End for decades after the disaster.

[37][38] Many laws and regulations governing construction were changed as a direct result of the disaster, including requirements for oversight by a licensed architect and civil engineer.

- Purity Distilling molasses tank

- Firehouse 31 (heavy damage)

- Paving department and police station

- Purity offices (flattened)

- Copps Hill Terrace

- Boston Gas Light building (damaged)

- Purity warehouse (mostly intact)

- Residential area (site of flattened Clougherty house)