James Boswell

[2][3] A great mass of Boswell's diaries, letters, and private papers were recovered from the 1920s to the 1950s, and their publication by Yale University has transformed his reputation.

Boswell was born in Blair's Land on the east side of Parliament Close behind St Giles' Cathedral in Edinburgh on 29 October 1740 (N.S.).

Kay Jamison, Professor of Psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, in her book Touched with Fire, believes that Boswell may have suffered from bipolar disorder,[4] and this condition would afflict him sporadically all through his life.

At the age of five, he was sent to James Mundell's academy, an advanced institution by the standards of the time, where he was instructed in English, Latin, writing and arithmetic.

Instead of obeying, though, Boswell ran away to London, where he spent three months, living the life of a libertine, before he was taken back to Scotland by his father.

On 30 July 1762, Boswell passed his oral law exam, after which his father decided to raise his allowance to £200 a year and permitted him to return to London.

"[6]On 6 August, Boswell departed England for Europe, with the initial goal of continuing his law studies at Utrecht University.

He befriended and fell in love with Isabelle de Charrière, also known as Belle van Zuylen, a vivacious young Dutchwoman of unorthodox opinions, his social and intellectual superior.

He arranged to meet European intellectuals Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire with a recommendation letter of Constant d'Hermenches, and made a pilgrimage to Rome, where his portrait was painted by George Willison.

Boswell also travelled to Corsica and spent seven weeks there, meeting the Corsican resistance leader Pasquale Paoli, and sending reports to London newspapers.

Boswell returned to London in February 1766 accompanied by Rousseau's mistress Thérèse Levasseur, with whom he had a brief affair on the journey home.

[7] After spending a few weeks in the capital, he returned to Scotland, buying (or perhaps renting) the former house of David Hume on James Court on the Lawnmarket.

He practised the law in Edinburgh for over a decade, and most years spent his annual break in London, mingling with Johnson and many other London-based writers, editors, and printers, and furthering his literary ambitions.

"[12] A few years earlier, he wrote that during a night with an actress named Louisa, "five times was I fairly lost in supreme rapture.

His character mixed a superficial Enlightenment sensibility for reason and taste with a genuine and somewhat romantic love of the sublime and a propensity for occasionally puerile whimsy.

The latter, along with his tendency for drink and other vices, caused many contemporaries and later observers to regard him as being too lightweight to be an equal in the literary crowd that he wanted to be a part of.

For example, a later edition of Traditions of Edinburgh by Robert Chambers suggests that Boswell's residence at James Court was actually in the Western wing.

After Johnson's death in 1784, Boswell moved to London to try his luck at the English Bar, which proved even less successful than his career in Scotland.

In 1792 Boswell lobbied the Home Secretary to help gain royal pardons for four Botany Bay escapees, including Mary Bryant.

When the Life of Samuel Johnson was published in 1791, its style was unique in that, unlike other biographies of that era, it directly incorporated conversations that Boswell had noted down at the time for his journals.

Instead of writing a strictly fact-based record of Johnson's public life in the style of the time, he painted a more personal and intimate portrait of the man than was normal in biographies of the day.

The former argued that Boswell's uninhibited folly and candour were his greatest qualifications; the latter replied that beneath such traits was a mind to discern excellence and a heart to appreciate it, aided by the power of accurate observation and considerable dramatic ability.

In the 1920s a great part of Boswell's private papers, including intimate journals for much of his life, were discovered at Malahide Castle, north of Dublin.

Publication of the research edition of Boswell's journals and letters, each including never before published material, was ceased by Yale University in June 2021, prior to the completion of the project[why?].

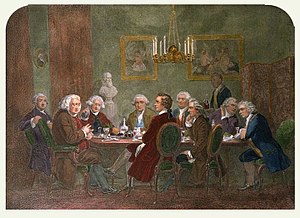

His journals also record meetings and conversations with eminent individuals belonging to The Club, including Lord Monboddo, David Garrick, Edmund Burke, Joshua Reynolds and Oliver Goldsmith.

In "A Scandal in Bohemia", Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's character Sherlock Holmes affectionately says of Dr. Watson, who narrates the tales, "I am lost without my Boswell.

The novel, which includes scenes that feature Samuel Johnson, is a thriller that focuses on the tense relationship between James and his younger brother John.

[30] After Boswell's private papers were recovered, and brought together by Ralph Isham, they were acquired by Yale University, where a dedicated office was established to edit and publish his journals and correspondence.