Bothriolepis

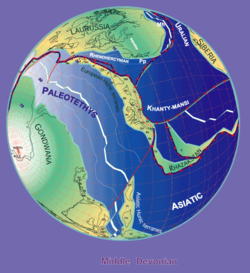

Historically, Bothriolepis resided in an array of paleo-environments spread across every paleocontinent, including near shore marine and freshwater settings.

[1] Most species of Bothriolepis were characterized as relatively small, benthic, freshwater detritivores (organisms that obtain nutrients by consuming decomposing plant/animal material), averaging around 30 centimetres (12 in) in length.

Antiarchs, as well as other placoderms, are morphologically diverse and are characterized by bony plates that cover their head and the anterior part of the trunk.

[7] Additionally, the position of the mouth on the ventral side of the skull is consistent with the typical horizontal resting orientation of Bothriolepis.

It had a special feature on its skull, a separate partition of bone below the opening for the eyes and nostrils enclosing the nasal capsules called a preorbital recess.

A new sample from the Gogo Formation in the Canning Basin of Western Australia has provided evidence regarding the morphological features of the visceral jaw elements of Bothriolepis.

[8] In addition to the above-listed sample from the Gogo Formation, several other specimens have been found with mouthparts held in the natural position by a membrane that covers the oral region and attaches to the lateral and anterior margins of the head.

Attached to the ventral surface of the trunk is a large, thin, circular plate marked by deep-lying lines and superficial ridges.

These spike-like fins were probably used to lift the body clear off the bottom; its heavy armor would have made it sink quickly as soon as it lost forward momentum.

Three different sediment types were identified within the different sections of Bothriolepis: the first a pale greenish-gray medium-textured sandstone largely consisting of calcite; the second similar but finer sediment which preserves many of the organ forms; and the third distinct, fine-grained siltstone consisting of quartz, mica and other minerals but no calcite.

[7] These sediments helped preserve the following internal elements: In general, the alimentary system of Bothriolepis –which includes the organs involved in ingestion, digestion, and removal of waste– can be described as simple and straight, unlike that of humans.

It begins at the anterior end of the organism with a small mouth cavity located over the posterior area of the upper jaw plates.

Posteriorly from the mouth, the alimentary system extends into a wider and dorso-ventrally flattened region called the pharynx, from which both the gills and lungs arise.

While the alimentary system is primitive in nature and lacks an expanded stomach region, it is specialized by an independently acquired complex spiral valve, comparable to that in elasmobranchs and many bony fish and similar to that found in some sharks.

[7] It has been hypothesized that these lungs, coupled with the jointed arms and rigid, supportive skeleton, would have allowed Bothriolepis to travel on land.

For example, in his paper "Lungs" in Placoderms, a Persistent Palaeobiological Myth Related to Environmental Preconceived Interpretations, D. Goujet suggests that although traces of some digestive organs may be apparent from the sedimentary structures, there is no evidence supporting the presence of lungs in the samples from the Escuminac formation of Canada upon which the original assertion was based.

The Catskill Formation (Upper Devonian, Famennian Stage), located in Tioga County, Pennsylvania, is the site of a large sample of small individuals of Bothriolepis.

[3] Bothriolepis canadensis is a taxon that often serves as a model organism for the order Antiarchi because of its enormous sample of complete, intact specimens found at the Escuminac Formation in Quebec, Canada.

[1] Because of the vast sample size, this species is often used to compare growth data of newly acquired specimens of Bothriolepis, including those found in the Catskill Formation mentioned above.

This comparison allows researchers to determine if newly found samples represent juvenile individuals or new "Bothriolepis" species.

In 1948, E. Stensio released a detailed depiction of B. canadensis anatomy using an abundance of material, which eventually became the most widely accepted description of this species.

The external skeleton of Bothriolepis canadensis is made of cellular dermal bone tissue and is characterized by distinct horizontal zonation or stratification.

This site, the Waterloo Farm lagerstätte is interpreted as representing a back barrier coastal lagoonal setting with both marine and fluvial influences.

[21] Gess observed that Bothriolepis was less abundant at the Waterloo Farm site than at most Bothriolepis-bearing localities, though a full ontogenetic series is represented.

B. nitida has a maximum headshield length of 65 millimetres (2.6 in), a narrow and shallow trifid preorbital recess, has an anterior-median-dorsal (AMD) plate that is wider than it is long and a ventral thoracic shield that has convex lateral borders.

By Stampfli & Borel, 2000