Boudica

Boudica or Boudicca (/ˈbuːdɪkə, boʊˈdɪkə/, from Brythonic *boudi 'victory, win' + *-kā 'having' suffix, i.e. 'Victorious Woman', known in Latin chronicles as Boadicea or Boudicea, and in Welsh as Buddug, pronounced [ˈbɨðɨɡ]) was a queen of the ancient British Iceni tribe, who led a failed uprising against the conquering forces of the Roman Empire in AD 60 or 61.

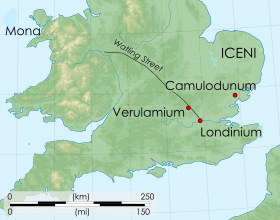

Upon hearing of the revolt, the Roman governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus hurried from the island of Mona (modern Anglesey) to Londinium, the 20-year-old commercial settlement that was the rebels' next target.

The crisis of 60/61 caused Nero to consider withdrawing all his imperial forces from Britain, but Suetonius's victory over Boudica confirmed Roman control of the province.

[4] Tacitus wrote some years after the rebellion, but his father-in-law Gnaeus Julius Agricola was an eyewitness to the events, having served in Britain as a tribune under Suetonius Paulinus during this period.

[2][4][7] Although imaginary, these speeches, designed to provide a comparison for readers of the antagonists' demands and approaches to war, and to portray the Romans as morally superior to their enemy, helped create an image of patriotism that turned Boudica into a legendary figure.

[8][9] Whilst the vast majority of historians accept Boudica as a historial figure, a small minority have questioned whether she existed based on the lack of contemporary sources and archaeological evidence.

The Romans' next actions were described by Tacitus, who detailed pillaging of the countryside, the ransacking of the king's household, and the brutal treatment of Boudica and her daughters.

[15] The willingness of those seen as barbarians to sacrifice a higher quality of living under the Romans in exchange for their freedom and personal liberty was an important part of what Dio considered to be motivation for the rebellions.

[20] Once the revolt had begun, the only Roman troops available to provide assistance, aside from the few within the colony, were 200 auxiliaries located in London, who were not equipped to fight Boudica's army.

[19] He moved quickly with a force of men through hostile territory to Londinium, which he reached before the arrival of Boudica's army[22] but, outnumbered, he decided to abandon the town to the rebels, who burned it down after torturing and killing everyone who had remained.

[27] Dio adds that the noblest women were impaled on spikes and had their breasts cut off and sewn to their mouths, "to the accompaniment of sacrifices, banquets, and wanton behaviour" in sacred places, particularly the groves of Andraste.

[33] William Cowper used this spelling in his poem Boadicea, an Ode (1782), a work whose impact resulted in Boudica's reinvention as a British imperialistic champion.

[36] One of the earliest possible mentions of Boudica (excluding Tacitus' and Dio's accounts) was the 6th-century work De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae by the British monk Gildas.

In it, he demonstrates his knowledge of a female leader whom he describes as a "treacherous lioness" who "butchered the governors who had been left to give fuller voice and strength to the endeavours of Roman rule.

"[37] Both Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731) and the 9th-century work Historia Brittonum by the Welsh monk Nennius include references to the uprising of 60/61, but do not mention Boudica.

Dio, writing more than a century after her death, provided a detailed description of the Iceni queen (translated in 1925): "In stature she was very tall, in appearance most terrifying, in the glance of her eye most fierce, and her voice was harsh; a great mass of the tawniest hair fell to her hips; around her neck was a large golden necklace; and she wore a tunic of divers colours over which a thick mantle was fastened with a brooch.

[39][41] A narrative by the Florentine scholar Petruccio Ubaldini in The Lives of the Noble Ladies of the Kingdom of England and Scotland (1591) includes two female characters, 'Voadicia' and 'Bunduica', both based on Boudica.

[47] Illustrations of Boudica during this period—such as in Edward Barnard's New, Complete and Authentic History of England (1790) and the drawing by Thomas Stothard of the queen as a classical heroine—lacked historical accuracy.

The illustration of Boudica by Robert Havell in Charles Hamilton Smith's The Costume of the Original Inhabitants of the British Islands from the Earliest Periods to the Sixth Century (1815) was an early attempt to depict her in an historically accurate way.

[48] Cowper's 1782 poem Boadicea: An Ode was the most notable literary work to champion the resistance of the Britons, and helped to project British ideas of imperial expansion.

[50] A range of Victorian children's books mentioned Boudica; Beric the Briton (1893), a novel by G. A. Henty, with illustrations by William Parkinson, had a text based on the accounts of Tacitus and Dio.

[51] Boadicea and Her Daughters, a statue of the queen in her war chariot, complete with anachronistic scythes on the wheel axles, was executed by the sculptor Thomas Thornycroft.

[54] At Colchester Town Hall, a life-sized statue of Boudica stands on the south facade, sculpted by L J Watts in 1902; another depiction of her is in a stained glass window by Clayton and Bell in the council chamber.

She appears as a character in A Pageant of Great Women written by Cicely Hamilton, which opened at the Scala Theatre, London, in November 1909 before a national tour, and she was described in a 1909 pamphlet as "the eternal feminine... the guardian of the hearth, the avenger of its wrongs upon the defacer and the despoiler".