Brabant Revolution

Despite the tacit support of Prussia, the independent United Belgian States, established in January 1790, received no foreign recognition and the rebels soon became divided along ideological lines.

In 1764, Joseph II, was elected as Holy Roman Emperor, ruling over a loosely unified federation of autonomous territories within Central Europe roughly equivalent to modern-day Belgium, Germany, Slovenia the Czech Republic and Austria.

[3] Joseph particularly disliked institutions which he considered "outdated", such as the established ultramontane Church whose allegiance to the papacy prevented the Emperor from having total control, which restricted efficient and centralist rule.

[4] Soon after taking power, in 1781, Joseph launched a low-key tour of inspection of the Austrian Netherlands during which he concluded reform in the territory was badly needed.

Within the states themselves, the "traditional" independence was considered extremely important and figures such as Jan-Baptist Verlooy had even begun to claim the linguistic unity of Flemish dialects as a sign of national identity in what is now Flanders.

[7] Propelled by his belief in the Enlightenment, soon after taking power, Joseph launched a number of reforms which he hoped would make the territories he controlled more efficient and easier to govern.

[9][4] The Edict was condemned by Cardinal Frankenberg who insisted that religious tolerance, the relaxation of censorship and the suppression of laws against the Jansenists all constituted an attack on the Catholic Church.

[12] A second decree abolished the ad hoc semi-feudal or ecclesiastical courts operated by the states and replaced them with a centralised system similar to that already in place in Austria.

Van der Noot publicly accused the reforms of violating the precedents established by the Joyous Entry of 1356 which was widely regarded as a traditional bill of rights for the region.

As disquiet in the Austrian Netherlands grew, thousands of Flemish and Brabant dissidents fled into the Dutch Republic to join the growing patriot army at Breda although the force remained relatively small.

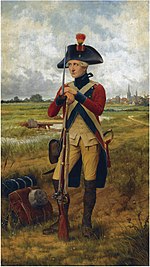

[20] On 30 August, Pro Aris et Focis voted to install Jean-André van der Mersch (or Vandermersch), a retired military officer, as the commander of the émigré army in Breda.

In August 1789, the inhabitants of the Prince-Bishopric of Liège also overthrew their tyrannical Prince-Bishop, César-Constantin-François de Hoensbroeck, in a bloodless coup d'état known as the "Happy Revolution" (Heureuse révolution).

[22] The Brabant Revolution broke out on 24 October 1789 when the émigré patriot army under Van der Mersch crossed over the Dutch border into the Austrian Netherlands.

[20] The army arrived in the town of Hoogstraten where a specially prepared document, the Manifesto of the People of Brabant (Manifeste du peuple brabançon), was read in the city hall.

[20][23] The rebel armies penetrated further into the territory, defeating Austrian forces in a number of small skirmishes, and captured the town of Mons on 21 November.

[22] Historians have pointed to the deliberate parallels between the entrance of the rebel army into the Austrian Netherlands in 1789 and Louis of Nassau's invasion of Frisia in 1566 which acted as the trigger for the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule.

Figures within revolutionary France, such as Jacques Pierre Brissot, praised their work and encouraged them to declare their own national independence in the spirit of the American Revolution.

By virtue of this power we have declared ourselves to be free and independent and have deprived and dismissed the former duke, Joseph II, from all sovereignty..." After the rebel capture of Brussels on 18 December, work soon began on a new constitution.

[27] In January, the rebels re-called the States-General, a traditional assembly composed of the provincial elites which had not met since the Middle Ages, to discuss the form the new state would take.

The Statists succeeded in gaining support in a number of Patriotic Associations (Patriottische Maatschappij), similar to the "clubs" of Revolutionary France, which were composed of members of the wealthy classes.

[33] An armed "crusade" of peasants, carrying crucifixes and led by priests, marched on Brussels in June to confirm their support of the Statists and to display rejection of the Enlightenment.

[32] Faced with an increasingly reactionary government in the United Belgian States, many of the exiled Vonckists felt that they had more to gain from negotiating with the Austrians than with the Statists.

[36] On 27 July 1790, Leopold signed the Reichenbach Convention with Prussia which allowed the Emperor to begin the reconquest of the Austrian Netherlands as long as its local traditions were respected.

[34] The Austrian army, under Field Marshal Blasius Columban, Baron von Bender, invaded in the United Belgian States and encountered little resistance from the population which was already discontented with the governance and infighting of the rebels.

[36] In the aftermath of the defeat of the United Belgian States, a convention was held at The Hague on 10 December 1790 to decide what form the Austrian reestablishment would take.

The Convention, which included representatives of the Emperor and the Triple Alliance of the Dutch, British and Prussians, eventually decided to cancel most of Joseph II's reforms.

[38] The exiled Vonckists in France embraced the French invasion of the territory as the only way to implement their own objectives, largely forgetting the nationalist dimension of their original ideologies.

The leading Belgian historian, Henri Pirenne, contrasted the Brabant Revolution, which he termed "defensive" or "conservative", with the more enlightened uprisings in France and Liège in his Histoire de Belgique series.

[37] The historians Jacques Godechot and Robert Roswell Palmer characterised the ideology of the French revolutionaries as founded on beliefs in the "enlightenment" and "national consciousness".

[45] Palmer argued for similarities between the Brabant Revolution and the counter-revolutionary activities of pre-revolutionary institutions, like the guilds and the aristocracy, in France which were ultimately defeated and abolished.